With pencil, you can always erase.

Sue Monk Kidd

With pencil, you can always erase.

Sue Monk Kidd

The worst thing you can do is censor yourself as the pencil hits the paper. You must not edit until you get it all on paper. If you can put everything down, stream-of-consciousness, you’ll do yourself a service.

Stephen Sondheim

Map out your future – but do it in pencil. The road ahead is as long as you make it. Make it worth the trip.

Jon Bon Jovi

Do you have hands? Excellent. That’s a good start. Can you hold a pencil? Great. If you have a sketchbook, open it and start by making a line, a mark, wherever. Doodle

Chris Riddell

It is the very mutability of the pencil mark that enables one to keep thinking in process.

Peter Saville

Before you run off, consider Tom. Other than Mrs. Steed’s eighth grade art class, he’s never drawn a thing. Other than that high school short story project (grade = D), Tom’s never written a thing (ignoring the occasional grocery list). Other than humming the high school Alma Mater during his class’s tenth-year reunion, Tom’s never been much into music.

So, Tom’s not the creative type. Or so he thinks. But remember, Tom is human and non-creative humans are an anomaly, or they don’t survive.

If we look closer at Tom, we learn he likes to build stuff, things like knives, swords, meat cleavers, and small wood-burning heaters and pizza ovens (he’s also built a farm carryall). Sure, he uses tools: sanders, grinders, welders, air-compressors. But his designs are unique to him.

Tom’s metal-working isn’t a job; he does it to fight depression, and to battle the boredom of his day job (he’s a truck driver and delivers feed to poultry houses). Of late, Tom’s been thinking of a dream he had a few weeks ago. He was walking down an aisle towards a podium to receive the educator of the year award. The dream, or some variant of its theme, comes now at least twice a month.

Well, what do you know? Tom is creative, even though it might seem involuntary. He has an imagination, albeit fueled by the mysterious dream world. Truth be told, Tom would love to teach metal-working at the local technical college.

You and I are a lot like Tom, at least at times. We have hopes and dreams, and we get discouraged, maybe slid into depression.

Mine dream is to become a better novelist, all while encouraging others to write fiction. Yours might be to draw or paint landscapes, write poetry or short-stories, or learn how to play the guitar.

Whatever our dreams and hopes, it likely involves doing something, learning better ways of doing something. Doing and being require a multitude of skills (some of which we already have). Even if you were born knowing Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata (unlikely!), you still have room to learn and grow.

Here’s some good advice from famous poet Jane Kenyon:

“Be a good steward of your gifts. Protect your time. Feed your inner life. Avoid too much noise. Read good books, have good sentences in your ears. Be by yourself as often as you can. Walk. Take the phone off the hook. Work regular hours.”

I encourage you to read Maria Popova’s article: Poet Jane Kenyon’s Advice on Writing: Some of the Wisest Words to Create and Live By.

Hold on a minute. Merriam Webster states there are two definitions for addiction. Here they are:

“1: a strong and harmful need to regularly have something (such as a drug) or do something (such as gamble). He has a drug addiction. His life has been ruined by heroin addiction.

2: an unusually great interest in something or a need to do or have something. He devotes his summers to his surfing addiction.”

Forget the first one. My post title refers only to the second. I’m addicted to writing fiction and you should be too. Gosh, that’s emphatic, assessing your situation without knowing your specific ailments.

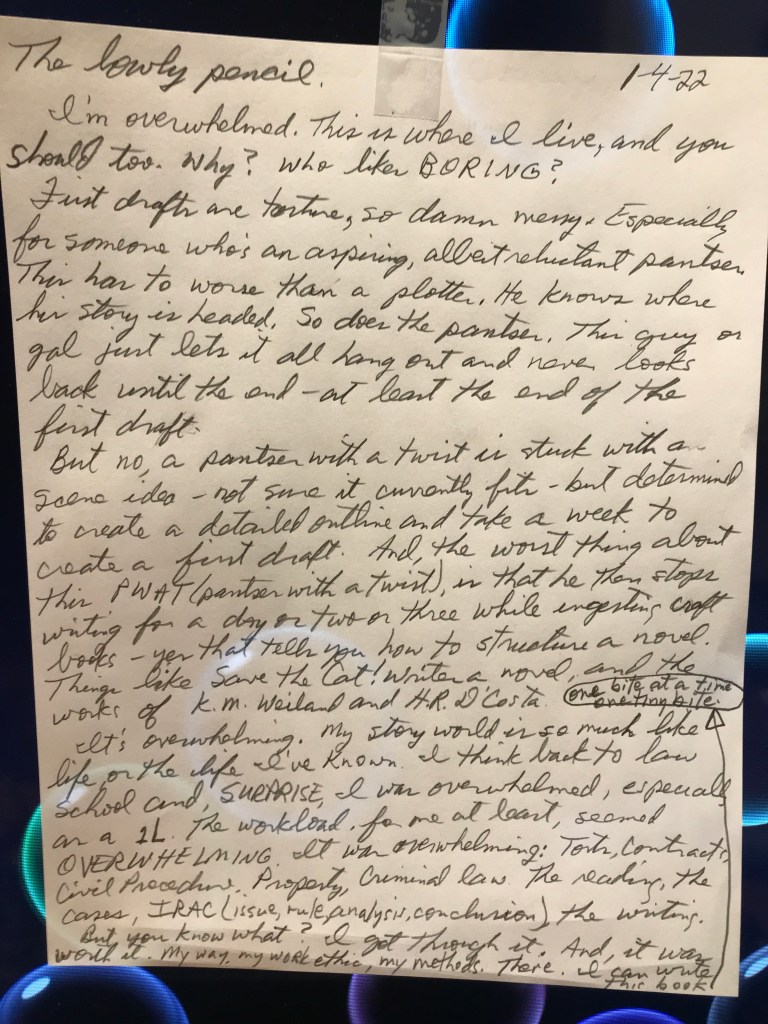

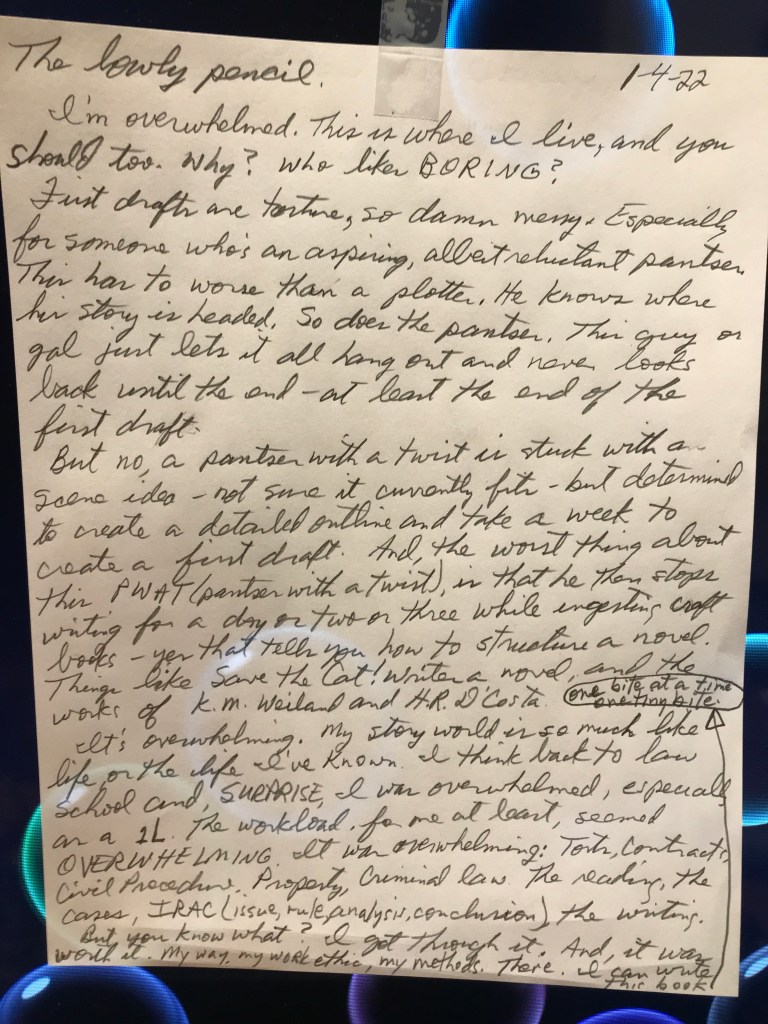

On December the first, I announced I wasn’t going to blog anymore, at least for the time being. But, remember, I’m an addict. In fact, my addiction is two-pronged: an unquenchable need to write fiction, and the same desire to convince you to do the same. Why? Because writing fiction will transform your life. My website title and tag line says it this way: The Pencil Driven Life [g]ives you a mission & transforms your wounds, traumas, & mistakes into a life of meaning & purpose.

I’d like to share with you several points from an article I read the other day. But, first, let me address changes I’ve made. First, as stated above, the title of my website is now The Pencil Driven Life. This phrase has been around for a while because it encapsulates my life over the past six years. Until recently, this phrase was the title of my blog. Now, that’s changed to Write to Life.

In a nutshell, the Write to Life blog is intended to reveal the answer to “Why write fiction?” Catchy uh? Seriously, my blog’s title is meant to convey at least two meanings: you and I have a right to life. And, we can write our way to life, real life, which, ties directly to my website title, The Pencil Driven Life. This Life is all about reading and writing fiction, which, if we’re serious, will enable us to write our way to a wonderful life (note, I’m not saying you’ll become rich financially) of peace, contentment, and compassion.

One other change I’ll mention before we look at that article. I’ve created the Fiction Writing School. No, this isn’t a formal brick and mortar school. In fact, it’s not formal at all. It’s a site you can visit by clicking on the Writing School menu option (or, clicking here) anytime and find connections to five-star authors and teachers I’ve found to truly ‘know their fiction writing stuff.’ In addition, I include links to articles and YouTube episodes and channels I’ve found useful and important. Periodically, I’ll also include my own fiction writing advice or instruction. At least once per week, I’ll update the ‘School’s’ offerings. In a nutshell, the Fiction Writing School is intended to reveal the answer(s) to,“How to write fiction?”

Now, let me address that article I mentioned: “The Therapeutic Benefits of Writing a Novel,” by Jessica Lourey. I loved her story because it was my story. Now, I’m certainly not saying that the shock I encountered was anything as bad as what Jessica did: she lost her husband to suicide. But, living a lie for fifty-six years (not counting the first five years of my life) and slowly over the last six years learning the truth, isn’t a bed of roses. My shock, translated: being a diehard Southern Baptist Fundamentalist most all my life, then learning (albeit slowly) there’s little to any credible evidence for its truthfulness.

My intent in transitioning to the real benefits of writing a novel is simply to say, we all, you, me, and everyone we know, has experienced a shock (or two or three) that is hard to shack off and recover from. In a most accurate sense, every new novelist starts at the same place–we each bring wounds to the page. Plus, I think it’s safe to say, we all want things to be better, we each want a way to offload the pain we carry around like a saddle on our backs. In Jessica’s words, “I needed to get it out of my head or it was going to destroy me. Channeling it into fiction seemed like the safest method.”

Fictionalizing your own painful experiences is a way to unbuckle that saddle. Offloading what happened to you onto the written page and inside your imagined characters creates space in your own head for more healthy thoughts. This paves the way to healing.

Jessica says there are two key elements that make this possible, “creating a coherent narrative and shifting perspective.” In fiction writing parlance, these are plot and point of view.

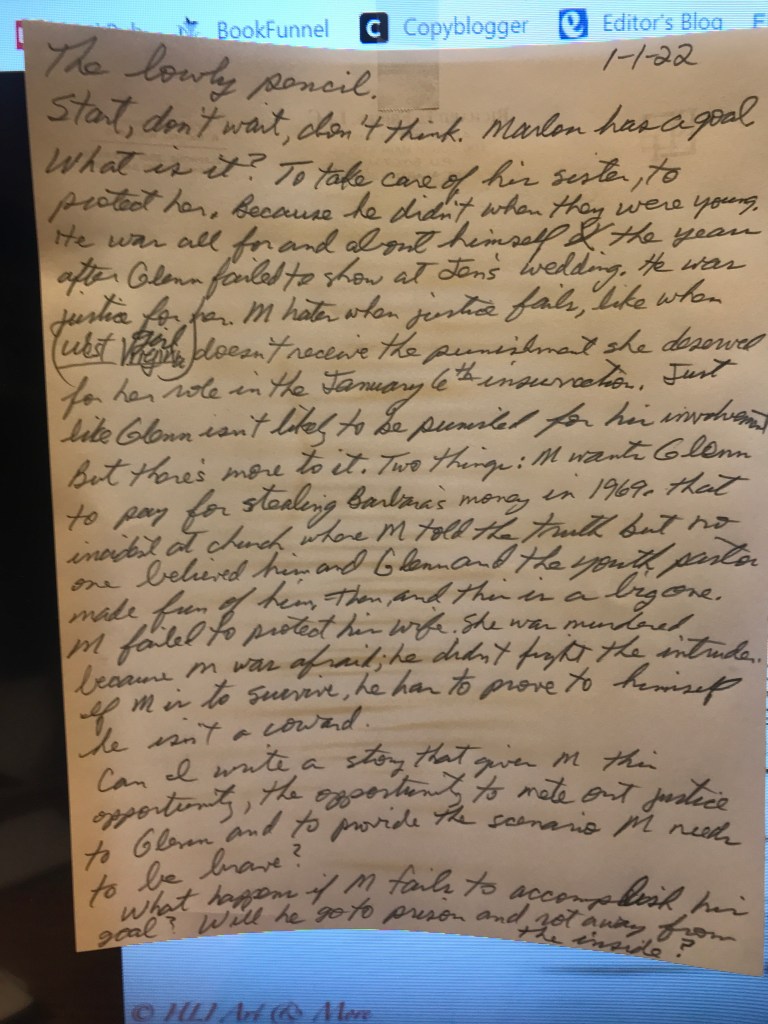

Of course, you can write a novel about most anything, but, if the main purpose is to heal, or, at least, begin the healing process, then the novel will be about events and circumstances surrounding your own painful experience. We could call it “your wound.”

I like what Jessica says in this regard, “The power of this process is transformative. Writing fiction allows you to become a spectator to life’s roughest seas. It gives form to your wandering thoughts, lends empathy to your perspective, allows you to cultivate compassion and wisdom by considering other people’s motivations, and provides us practice in controlling attention, emotion, and outcome. We heal when we transmute the chaos of life into the structure of a novel, when we learn to walk through the world as observers and students rather than wounded, when we make choices about what parts of a story are important and what we can let go of.”

In a not-so-logical way, my first novel was transformative. As stated above, I reached the point I was ready to explode, not so much that I was angry at any one else, I was angry with myself for never questioning what I believed. So, I channeled my anger into a young adult book (probably thinking I wish I’d had this book when I was a kid, and hoping that every teenager would read it). My novel was an in-your-face type reply to the half-century I’d wasting believing a fairy tale.

God and Girl is about Ruthie, the teenage daughter of Southern Baptist preacher Joseph Brown. She is a good kid, and loves her faith, and her family. Then, during the summer after her eighth grade, she meets Ellen Ayers who’s just moved to town and, like Ruthie, will be a ninth grader at Boaz High School where Ellen’s mom will begin teaching Biology. Ruthie and Ellen fall passionately in love. That’s all I’ll say about my little story, but, you get the picture (God and Girl). Writing my first novel was no doubt therapeutic and began my journey to recovery and healing.

To gather every nugget available, click and read, “The Therapeutic Benefits of Writing a Novel.” Please read it once, twice, or three times.

Then, start pondering that novel anchoring your life to the bottomless pit of despair. You know it, you feel it every day. It greets you when you wake every morning (assuming you slept), it makes you stumble when crossing the kitchen for your first cup of coffee, it punches you in the gut more than once before mid-morning. I’ll stop, but it doesn’t.

What your painful wound needs is a way out, and you need it too. Could letting it escape through your mind and fingers, and gluing it to the written page, begin your journey to recovery and on to healing?

Think about it. And yes, it’s okay to reread “The Therapeutic Benefits of Writing a Novel.”