Here’s the link to this article.

Shane Miller

Fictionary Certified StoryCoach Author

June 17, 2024

Ah, starting a story.

The stage of the process that stirs all the feels within your writerly brain. You’ve sparked your initial idea. You’ve penned your perfect, pristine outline. Now, you’re finally sitting down to start your story, fingers poised over your expectant keyboard, and nothing happens.

Where are the flowing words, pouring onto the page like warm custard drizzled over a sticky toffee pudding (other desserts are available)? Where’s all that witty dialogue you’ve spent days thinking (and laughing) about? And why aren’t your characters jumping into action and doing something?

You stare at the blinking cursor, unable to type a single thing, worried you’ll never write another word again.

The problem isn’t you, your idea, or your novel. Chances are, if you find yourself in this situation, just like I did when I first started writing books, it’s because you don’t know how to start a novel in a way that’s going to hook readers in and make them read past page one.

Don’t feel bad about it. We’ve all been there, and it’s a really common problem. After all, there’s so much content out there about how to plot novels (no writer can walk ten paces without tripping over a story outlining template), how to write sparkling dialogue, and how to write emotion that feels real, it’s no wonder you feel you’ve got those things down.

And, while all these guides are a fantastic addition to your storytelling arsenal, very few of them teach you how to actually start writing your novel, or how to write the beginning of your novel well.

If you’ve ever suffered from the dreaded blinking cursor syndrome, then fear not, because this article is for you. By the time you’ve finished reading, I’ll have armed you with so many tools and tips for how to write a brilliant beginning, you’ll never stress out over that blinking cursor again.

But, before we get to that, I guess we should talk about when to write the start of your story.

When to Write the Start of Your Story

The answer to this question very much depends on whether you’re a plotter, or a discovery writer. If you’re an extreme plotter (like me), then you won’t feel ready to start your novel until you’ve:

- Worked out what your key plot points are (inciting incident, plot point 1, midpoint, plot point 2, climax)

- Got to know your characters by writing an in-depth profile for each one

- Sorted out all your settings by working out which locations you need to include in your novel, thought about how those locations resonate emotionally, and written out the sensory information you’ll include

- Named each scene in three words or fewer so you know where the story is going

- Outlined each scene by jotting down a few notes about what’s going to happen as the story progresses

If outlining a novel in this much detail energizes you, chances are you’re an extreme plotter too. If, however, you’re getting hives at the mere thought of the words character profile, then it’s likely you’re an extreme discovery writer, meaning you like to launch straight into writing the story and let everything unfold naturally.

The important thing is, neither of these approaches is wrong. As authors, we need to do whatever works for us so we can get those first words on the page. And, don’t forget, this whole plotter/discovery writer thing is a spectrum.

Maybe you like to plan characters, but you don’t want to plot. Or perhaps you need to see your settings in your mind before you write, but characters jump out at you as the story unfolds.That’s fine too.

There are so many ways to prepare for writing a novel, but for putting pen to paper and opening your story in a way that’s going to delight readers, there are some hard and fast tips. And, if you get the start of your novel right, readers will keep flipping pages until the very end.

How to Start a Book in 6 Steps

Now we’ve covered the plotting vs. discovery writing debate, let’s get to the main event and explore how we open novels in ways readers love.

You’re about to discover how to start your novel, and I’m so excited for you. As an overview, here’s what we’re going to cover:

- The Opening Line: How to write an opening line that hooks readers

- Character Creation: How to create characters readers can relate to

- World Building: How to build a world that feels real

- Starting with the End in Mind: How to set up your protagonist’s journey in the opening pages

- Setting the Right Tone: How to hit the right evocative notes at the start of your book

- Using the Five Senses: How to immerse readers in your story from the first page

Let’s jump right in and talk about one of my favorite things. How to make your novel’s opening line hooky.

How to Write an Opening Line

If you want to convince readers to carry on reading once they pick your book (hint: you do), then you need to get their attention. And don’t forget, we’re not only competing with other authors for our reader’s attention. We’re also competing with social media, Netflix, Spotify, and pretty much every other entertainment medium that’s vying for our reader’s attention.

And the best way to get (and keep) your readers’ attention is to write a hooky opening line that’s guaranteed to make them sit up and take notice.

Coming up a little later, I’ll share some of the most popular ways to kick off your story with a great opening line and some killer examples from popular books that do it brilliantly. First though, I want to share my go to method for writing an opening line that will stick in your readers’ minds long after they close your novel.

There’s this little trick I like to call the invisible question.

When you ask your readers an implicit question, or a question that doesn’t have a question mark, in your opening line, they psychologically need to answer it. The key is, readers can only answer the invisible question you ask them by reading on. And, if you can include a hint about the characters, plot, and/or setting in your opening line, so much the better, because readers will connect to the story that much more.

So, the structure for the invisible question is a statement that pulls triple duty by doing all three of these things:

- Makes the reader ask themselves a question

- Makes the reader want to read on to find out the answer

- Hints at the characters, plot, or setting

This isn’t the only way to open a story, and we’ll cover some others a little later, but so you really get to grips with my favorite method, let’s look at some examples from bestselling books, so you can see how the masters do it.

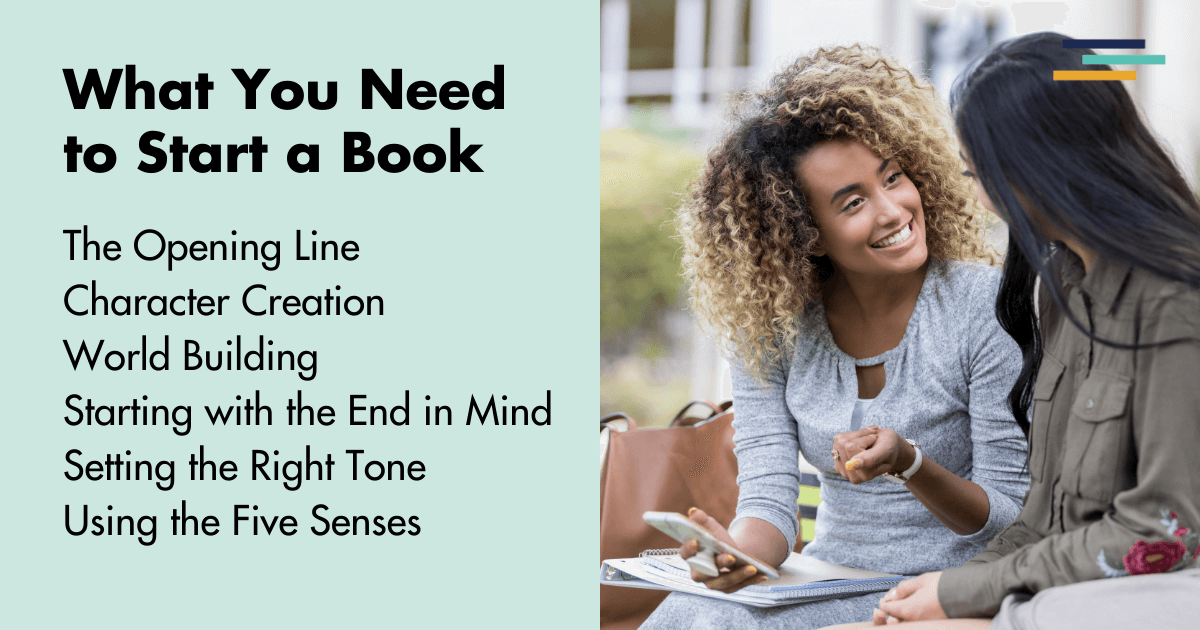

Examples of the Invisible Question from Bestselling Books

Endgame: The Calling by James Frey (YA Dystopian Sci-fi)

Endgame’s opening line is:

“Endgame has begun.”

Using three simple words, James Frey has created a fantastic invisible question. Let’s break it down and analyze why it works:

- Endgame is an unfamiliar word in this context, so readers will immediately ask themselves, “What is Endgame?”

- This unfamiliar concept drives readers to read on and find out what Endgame actually is.

- Frey tells us that whatever the plot is, it’s going to take place within the confines of Endgame, and Endgame is going to be the major source of conflict.

The Hating Game by Sally Throne (Contemporary Enemies to Lovers Romance)

The Hating Game’s opening line is:

“I have a theory. Hating someone feels disturbingly similar to being in love with them.”

Here’s why this one is a winner:

- The opening line is a jarring comparison, which makes the reader ask themselves, “How can love and hate be similar?”

- Again, they can only find out the answer by reading on, so Thorne is playing on our psychological need for answers.

- The opening line tells us the protagonist, Lucy Hutton, is a woman with strong opinions.

The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown (Action Thriller)

Lastly, the opening line of The Da Vinci Code is:

“Renowned curator Jacques Sauniere staggered through the vaulted archway of the museum’s grand gallery.”

Now this one is a work of pure genius because the invisible question stems from the use of one word staggered. Brown could’ve chosen the word walked, but it wouldn’t have had the same effect. Anyone can walk through an archway, but if someone’s staggering, readers ask themselves:

- “Why is Jacques staggering?” (i.e. Is he wounded? Is he ill? Is something else wrong?)

- You guessed it, readers will only find out if they keep flipping pages.

- We get information about the character (Jacques) and the setting (the museum).

See how using an invisible question to open your novel is a surefire way to grab your readers’ attention?

Next up, let’s look at one of the most critical aspects of starting your novels well, character creation.

How to Write Memorable Characters

A novel without relatable characters is like toast without peanut butter. Bland.

But, if you can get readers to relate to your characters when they first meet them (and combine this with a cracker of an opening line), then you’re winning.

Did you just groan? I don’t blame you. As soon as I say the words character creation, most people give me that reaction, and I know why. Character creation is synonymous with those long-winded character questionnaires filled with questions designed to make you run, screaming for the hills.

I might be a heavy plotter, but I don’t need to know the name of my protagonist’s third grade teacher’s dog.

Instead, we’re going to stick to the five foundations of a relatable character and how they make readers connect with the people you put on your pages.

The Five Foundations of a Relatable Character

When creating your cast of characters, give every single major character these five things:

- A Wound: A past event that’s injured them physically, mentally, emotionally, or all three

- A Flaw: All deep wounds leave scars, and a character’s scar is the flaw, or the way the wound negatively affects their behavior when the novel opens

- A Goal: The major external goal they’re chasing throughout the novel (e.g., in a heist thriller, this could be to steal a famous painting)

- A Need: This is your character’s internal goal, or the life lesson they need to learn to fix their flaw

- A Uniqueness: An object, symbol, ability, catchphrase, or attitude belonging to this character alone, which makes them stand out from all the other characters in your novel

If you give each major character in your novel these five things, you’ve created a cast readers will resonate with. These five things are vital to create well-rounded protagonists.

Let’s look at a relatable protagonist readers love, Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games. Notice here that I didn’t say likable. Katniss is unlikable, but she is relatable, and you’ll see why in a moment.

Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins (YA Dystopian)

- Wound: Katniss’s father died in a mine explosion when she was twelve, which led to her mother neglecting Katniss and her little sister, Prim

- Flaw: Katniss feels betrayed by her mother so finds it hard to trust, and she certainly doesn’t want to get romantically involved with anyone because it only leads to loss.

- Goal: Her goal is to win The Hunger Games so she and her family can survive.

- Need: She needs to learn to rely on other people and let them in, which she gradually does through her romance subplot with Peeta.

- Uniqueness: Katniss’s uniqueness is her skill with a bow and arrow and, while other characters use the same weapon, she is the most skilled.

Because Suzanne Collins got Katniss’s five foundations in place, she created a character readers still talk about to this day and one we will remember for many years to come.

How to Build Your Story World

Seeing as you’ve just created well-rounded, relatable characters, it’s only fair we give them a shiny new world to play in.

Now, I won’t tell you what your cafè needs to look like if you’re writing a small town romance or what levers and gears your spaceship needs if you’re writing sci-fi. What I am going to do is remind you that every setting in your world should be influenced by your point of view character.

If your novel opens on a hot day, and your point of view character is grumpy by nature, they might bemoan the inferno-like heat of the sun and complain about how much they’re sweating. If, however, it’s a hot day, and your point of view character has a positive outlook, they might talk about how much they love to see the sun and how it makes everything seem more cheerful.

It’s the same setting with different characters and two unique interpretations because setting should inform character and character should inform setting.

It’s what I like to call a character driven world, and it’s a great way to invest readers in your books because they’ll connect to your world (and your point of view character) on a deeper level when they view your story world through that character’s unique lens.

The best example I’ve seen of a character driven world come from The Anatomy of a Scandal by Sarah Vaughn, so let’s take a sneak peek at how the author pulls it off so well in her opening paragraph.

“My wig slumps on my desk where I have tossed it. A beached jellyfish. Out of court, I am careless with this crucial part of my wardrobe, showing it the opposite of what it should command: respect. Hand made from horsehair and worth nearly six hundred pounds, I want it to accrue the gravitas I sometimes fear I lack. For the hairline to yellow with perspiration, the tight, cream curls to relax. Nineteen years since being called to the Bar, my wig is still that of a conscientious new girl – not a barrister who has inherited it from her, or more usually his, father. That’s the sort of wig I want: one dulled with the patina of tradition, entitlement and age.”

Although the entire paragraph sets up the courtroom setting, we also experience everything through the eyes of Kate Woodcroft. And her view of the world colors how it’s presented.

We know that if Kate’s wig cost six hundred pounds, she’s wealthy. We know she’s well educated because she uses words like “accrue,” “gravitas,” “conscientious.” and “patina.” You can tell that Kate’s upbringing was nothing like that of her colleagues and that it was likely working class because she didn’t inherit her wig.

We get all that from one paragraph. See why I believe Vaughan is a master of the character driven world?

Why You Should Start with the End in Mind

This next step builds on the character driven world.

When I say starting with the end in mind, I’m not talking about the last scene in your novel, although it’s helpful to have that endpoint in mind. I’m talking about knowing how your protagonist needs to grow by the end of the novel so they can finally beat that internal flaw and become the well-rounded person they deserve to be.

Why is it so important to know where your character ends up emotionally by the end of the novel? Because this makes readers care about your story. I like to think of it like this.

External Conflict = What Happens = Plot

Internal Conflict = Character Transformation = Story

Pretty much all the internal conflict in your novel stems from the internal journey your character takes throughout your story.

Readers don’t really care about the plot. Sure, they love the car chases, magic fights, and mad dashes to the airport to declare undying love. Who doesn’t? But they only become invested in the plot because these things are happening to a character they care about.

Remember when we discussed the five foundations of a character? You already know your protagonist’s wound and their flaw, so you know where they’re starting from emotionally, and you know how that flaw will be negatively affecting their behavior at the start of the novel.

You also know their need or the lesson they need to learn by the end of the novel to fix their flaw. The need is the opposite of the flaw.

So, if your protagonist starts off being afraid of conflict, you know that by the end of the novel they need to lean into conflict. If they start their story closed off to the possibility of finding love, then they need to have found, or be open to finding, love at the end of the novel.

By starting with the end in mind, you’ll be able to set up the protagonist’s character arc from page one. If you can show your protagonist’s flaw through the “wrong” actions they take at the start of the novel, readers will not only bond with your protagonist and feel empathy for them, they’ll also know—on a subconscious level—they’re going on a transformative journey with that character.

How to Set the Right Tone

If you’re writing a romance and you start with a murder, you’re probably striking the wrong tone. Similarly, if you’re writing a thriller and you open with a comedic scene, your book is going to feel tone deaf.

Your tone should match genre expectations. And if you get this wrong, you’ll disappoint readers who go into your book expecting one thing and end up getting something completely different.

Here’s how to set the right tone in five steps.

Tip 1: Point of View and Tense

Certain genres have expectations with POV and tense.

If you’re writing YA dystopian, go to your bookshelf and pull out some of the most popular books in that genre. You’ll find 99% of them are written in first person, present tense. Pull out an epic fantasy tome, however, and you’ll likely find a third person, past tense book.

Check out Divergent by Veronica Roth (YA Dystopian) and The Elfstones of Shannara by Terry Brooks (Epic Fantasy) if you want two examples.

Tip 2: Character Voice

If you get a character’s voice wrong, and your characters don’t sound like they belong in your world, you’ll be waving a red flag at readers that the tone is off.

Say you’re writing an urban fantasy novel. You’ll want your characters to sound snarky and modern. Compare this to a cozy mystery protagonist from the 1950s, and they’re going to sound completely different.

What you wouldn’t do is place that 1950s style character voice in an urban fantasy novel, and vice versa because it would sound wrong.

Check out Dead Witch Walking by Kim Harrison for an example of an urban fantasy character voice and Murder on the Riviera Express by TP Fielden for an example of a cozy mystery character voice.

Tip 3: Weather/Time of Day/Season

Ever notice how gritty thrillers open on dark and rainy nights and upbeat beach reads feature a lot of sunshine and daytime activities, or start at New Year’s Eve when there’s a fresh start just around the corner? The authors haven’t done that by accident. They’ve done it because it sets the right tone for their genre.

Take these two examples:

The Business of Dying by Simon Kernick (Thriller)

“09:01 p.m. We were sitting in the rear car park of The Traveller’s Rest Hotel. It was a typical English November night; dark, cold, and wet.”

It’s Not You, It’s Him by Sophie Ranald (Romantic Comedy)

“New Year’s Eve. If you ask me, it needs to take a long, hard look at itself. I mean, seriously. It has to be the most overrated night of the year, right?”

See how both authors set the right tone for their novels by opening with the expected weather/time of day/season?

Tip 4: Chapter Length

I’ll keep this brief, because it’s self explanatory, but authors like James Patterson, who write fast paced thrillers, favor shorter chapters. One of Patterson’s full-length novels might contain 100+ chapters. Contrast this with epic fantasy author, Peter S. Beagle, who wrote The Last Unicorn. The longest chapter in that book was over 20,000 words.

Pay attention to chapter lengths in your genre to hit the right tone,

Tip 5: Character Archetypes

The last thing to consider when setting the right tone is character archetypes. Certain kinds of characters always appear in certain genres. For example, the reluctant chosen one is a common character in epic fantasy, whereas the loner detective pops up again and again in crime thrillers.

Why You Should Use the Five Senses

Let’s talk about my favorite thing now. Using the five senses to fully immerse your readers in your story world when you open your novel.

The five senses are exactly what you’d expect:

- Sight: What you see

- Sound: What you hear

- Smell: What you smell

- Taste: What you taste

- Touch: What you feel

By using the five senses you can create a vivid experience of your settings for readers. A setting without sensory depth can’t exist like a 4D walkthrough experience in the reader’s mind, and that’s exactly what we need to create.

When we watch a movie, all the visuals and sounds are on screen for us to see, hear, and experience. Our readers don’t have that, so we need to help them out.

Without sight, readers won’t know what a new character looks like when they first appear on the page. Without sound, you can’t create a sense of atmosphere in your work. Smell is perfect if you want to trigger a flashback because the centers of our brains that control memory are linked to our olfactory glands. Using taste in unconventional ways (e.g., to describe the taste of magic in fantasy novels) can create unique sensory experiences for readers. And touch is great for describing temperature.

If you don’t want your novel to feel as flat as a steamrollered pancake, use the five senses and use them well.

Most Popular Ways to Start a Story

There are several popular ways to start a story and, I’m talking about the first line or paragraph of your novel. We’ve already covered one of them, which was the invisible question, but there are several other valid options as well.

Starting In Medias Res

Don’t let the fancy Latin scare you, my friend. Starting in medias res just means starting in the middle of the action. Think back to the last action thriller you read. Nine times out of ten, I’ll bet it started with a car chase, fight scene, or foot chase. This genre is where you need to go if you want a masterclass on starting your story in medias res.

Foreshadowing Trouble

Another popular technique. Foreshadowing trouble really means starting at a moment of tension that foreshadows conflict. This is the staple of the horror genre, whose books often open at a moment where something bad is about to happen and the reader needs to read on to discover whether the bad thing actually happens.

Using a Strong Line of Dialogue

Using a shocking, or strong, line of dialogue to open your novel is another way you can really make readers sit up and take notice. My advice, even if it’s not your thing, is to check out the opening line to Stephen King’s The Shining if you want to see how it’s done. I won’t repeat it here because it’s NSFW.

Raising an Actual Question

This is like the invisible question, but the line actually has a question mark at the end. It’s less subtle but serves the same purpose, to make the reader discover the answer to the question by reading on.

Not Wasting Words On Extraneous Description

Description slows down pacing, which is great for some areas of your novel where you want readers to sit and wallow in an emotional mess. The start of your novel isn’t the place for that. Your opening line needs to be hooky, punchy, and attention grabbing, so save descriptive passages until the reader is fully hooked in.

How to Start Off a Story Examples

See if you can spot which techniques these five outstanding authors used to create their hooky first lines.

The Fortune Men by Nafida Mohamed (Historical Fiction)

“‘The King is dead. Long live the Queen.’ The announcer’s voice crackles from the wireless and winds around the rapt patrons of Berlin’s Milk Bar as sinuously as the fog curls around the mournful street lamps, their wan glow barely illuminating the cobblestones.”

The Outsider by Albert Camus (Philosophical Fiction)

“Mother died today. Or maybe, yesterday; I can’t be sure.”

The Maze Runner by James Dashner (YA Dystopian)

“He began his new life standing up, surrounded by cold darkness, and stale, dusty air.”

A Discovery of Witches by Deborah Harkness (Paranormal Romance)

“The leather bound volume was nothing remarkable. To an ordinary historian, it would’ve looked no different from hundreds of other manuscripts in Oxford’s Bodleian Library, ancient and worn. But I knew there was something odd about it from the moment I collected it.”

The Restaurant at the End of the Universe by Douglas Adams (Sci-fi Comedy)

“The story so far: in the beginning, the universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.”

Tips for How to Start a Novel

Now you know everything you need to know to start your novel with a bang.

Let’s do a quick rundown of my six tips for starting a novel so they really bed themselves in:

- Make sure your opening line catches your readers’ attention.

- Create characters readers can relate to using the five foundations of a relatable protagonist.

- Build a character driven world by showing us how your POV characters view the world through their unique lens.

- Focus on your protagonist’s internal character arc so you can introduce their flaw in your novel’s opening pages.

- Set the right tone for your genre using POV and tense, character voice, weather/time of day/season, chapter length, and character archetypes.

- Use the five senses to immerse your readers in your world from the get go.

Do all this in your opening pages, and readers won’t be able to put your book down.

Want to supercharge those opening pages? Look no further than Fictionary, which can help you:

- Create engaging characters

- Pen interesting plots

- Structure solid settings

A tool like Fictionary helps you turn your opening pages into an interesting story readers love.