Yesterday, I finally focused on a task I’d been postponing for days. It was time for a new tag line for my website.

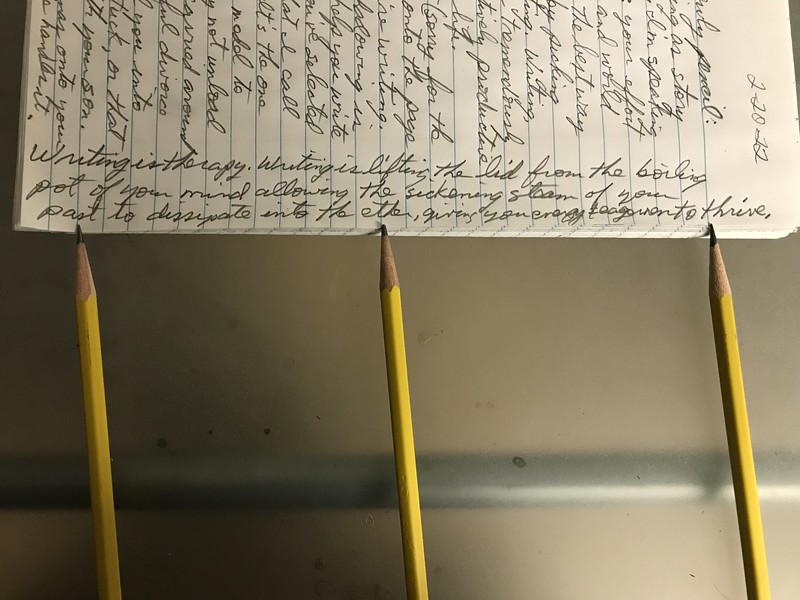

Even though my web address is my name, a year or so ago I’d given it a title that meant a lot to me personally: The Pencil Driven Life. I’d coined this phrase much earlier. Initially, it was created as a response to Rick Warren’s book, The Purpose Driven Life.

In it, Warren claims that God creates every human with a purpose. This comes about before each person is conceived. Although I once believed this, I no longer do. The Pencil Driven Life is simply the reverse, the opposite of Warren’s position. I now believe that there’s insufficient reason to believe Warren’s God exists. Thus, what naturally follows is that every person creates his or her own meaning; it comes from within, not from without. Each person decides what he wants to pursue. And, there’s no better creative tool than the lowly pencil. Properly used, this wonderful tool is a pathway to clarify one’s thinking and choosing what matters. It’s all about individual choice, not some supernatural force superimposing his/her/its choice.

My old tag line was: Reading and writing will change your life for the good. I wanted to make myself more clear. At bottom, I wanted my new tag line to express what I’d personally discovered since changing my religious beliefs, and starting a regular writing practice in 2015.

After an hour or so of thinking, doodling, considering various words and their definitions, and reviewing what many others have said about why they write, this is the current result: Writing is a tool for thinking, for discovering the truth obscured by a cluttered, unquestioning, and gullible mind.

Consider these words and their definitions (quotation marks omitted):

Cluttered–filled or scattered with a disorderly accumulation of objects or rubbish;

Unquestioning–not inclined to ask questions, being without doubt or reserve;

Gullible–naive and easily deceived or tricked.

Look carefully at the following quote. I don’t think anyone–ever–has better illustrated the necessity of writing.

I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.

Joan Didion

Note the meaning of necessity—“the condition of being essential or indispensable.” To Joan and many others, including me, writing is essential to a good life.

If we want to think better we need to start writing. Don’t believe this? Then, take this test. Sit down, alone, with as few distractions as possible. Start observing your mind. It won’t take long to discover it’s a mess (“dirty and disorderly”). Thoughts start appearing. You can’t stop them and most of them vanish as rapidly as they appear. It’s chaotic, disorderly. I close my eyes and my first thought is a snake story. More on this later.

None of this means writing isn’t messy. It is. Try it. You’ll soon conclude it’s a arduous process. The difference between initial thoughts and first scribblings, and a cogent representation of what you’re looking at, of what you’re seeing, and of what it means, is in the focusing, the determination, the doggedness of the rewriting.

Ernest Hemingway once said, “the only kind of writing is rewriting.” And, in the same vein, Robert Graves said, “there is no such thing as good writing, only good rewriting.” I’m certain Joan Didion would agree. It was not in her “easily deceived” mind or in her first marks on the page, but in her rewriting that she discovered what truly was obscured inside the cluttered back-room of her mind. I think it goes without saying that rewriting involves a ton of questioning.

Let’s talk about snakes. Today, I saw a 2014 abcNews article titled, “Snake-Handling Pentecostal Pastor Dies From Snake Bite.” Here’s the link. I encourage you to read it and watch the embedded video.

In a separate Google search, here’s what this pastor, Jamie Coots, said some years before his death in response to the question, “What does the Bible mean by taking up serpents?”

Takin’ up serpents, to me, it’s just showin’ that God has power over something that he created that does have the potential of injuring you or takin’ your life.

Jamie Coots

Was Mr. Coots correct? Let’s say we’d heard about snake handling, and learned that those who practiced it believed it’s how Jesus wanted Christians to demonstrate their faith. Maybe we’ve done some reading on the topic and even sat in a service at Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus Name in Middlesboro, Ky.

We’re back home now and want to sort things out–we want to find out what we’re thinking, what we’re looking at, what we see and what it means. What we want and what we fear. We grab a pencil and notepad and start brainstorming, jotting down a number of questions. Such as, what does the Bible actually say? And, what happened to Pastor Coots? Was he a true believer?

The abcNEWS article referenced Mark 16:18, so we look it up. As an aside, I recalled my beliefs from my sixty years as a Southern Baptist fundamentalist, and, after considering the above article and video, I quickly discover I’d never been as ‘fundamentalist’ as Jamie Coots.

For better context, here’s Mark 16:15-18 in the King James Version:

15 And he said unto them, Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature.

16 He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved; but he that believeth not shall be damned.

17 And these signs shall follow them that believe; In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues;

18 They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.

For comparison, here’s the passage in the New International Version:

15 [Jesus] said to them, “Go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation.

16 Whoever believes and is baptized will be saved, but whoever does not believe will be condemned.

17 And these signs will accompany those who believe: In my name they will drive out demons; they will speak in new tongues;

18 they will pick up snakes with their hands; and when they drink deadly poison, it will not hurt them at all; they will place their hands on sick people, and they will get well.

The first thing we note is the problem of interpreting verse 18. Ignoring the ‘taking up’ versus ‘picking up’ in the first part of this verse, it seems the subject is changed to drinking deadly poison. Do we assume it means the person with the snake in hand somehow drinks some of the snakes venom? That seems odd given what we know about how the venom is transferred via the snake’s bite. Oddly, it seems to say something else, that some other person, if they drink deadly poison, the result will be positve. “[I]t will not hurt them.”

For now, let’s skip over this and hypothesize Mark is saying a true believer can handle snakes and not be harmed. And, even further (since it’s all in the same verse; probably not the best assumption), the true believer’s action of snake handling will give them power to heal sick folks.

As to our question whether Mr. Coots was a true believer, it appears he either wasn’t or there’s something else going on. Again, look at the Coots quote from above: “Takin’ up serpents, to me, it’s just showin’ that God has power over something that he created that does have the potential of injuring you or takin’ your life.” We might ask ourselves concerning Coots, what happened to God’s power?

Can we conclude Jesus’ promise applies only to “believers”? True believers are saved. The snakes will not harm true believers. Why not scribble a note to the side of our paper: Right now I have grave doubts what I’m reading here in Mark represents reality.

We dig a little deeper. Let’s look back at our NIV Bible. At the end of Mark 16:8, there’s a footnote:

“Mark 16:8 Some manuscripts have the following ending between verses 8 and 9, and one manuscript has it after verse 8 (omitting verses 9-20): Then they quickly reported all these instructions to those around Peter. After this, Jesus himself also sent out through them from east to west the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation. Amen.”

Here’s verses 9-20 in the NIV:

9 When Jesus rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom he had driven seven demons. 10 She went and told those who had been with him and who were mourning and weeping. 11 When they heard that Jesus was alive and that she had seen him, they did not believe it. 12 Afterward Jesus appeared in a different form to two of them while they were walking in the country. 13 These returned and reported it to the rest; but they did not believe them either. 14 Later Jesus appeared to the Eleven as they were eating; he rebuked them for their lack of faith and their stubborn refusal to believe those who had seen him after he had risen. 15 He said to them, “Go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation. 16 Whoever believes and is baptized will be saved, but whoever does not believe will be condemned. 17 And these signs will accompany those who believe: In my name they will drive out demons; they will speak in new tongues; 18 they will pick up snakes with their hands; and when they drink deadly poison, it will not hurt them at all; they will place their hands on sick people, and they will get well.” 19 After the Lord Jesus had spoken to them, he was taken up into heaven and he sat at the right hand of God. 20 Then the disciples went out and preached everywhere, and the Lord worked with them and confirmed his word by the signs that accompanied it.

Two observations. First, it’s reasonable to conclude these verses were added to later manuscripts to support Jesus and a supernatural resurrection (see especially vs. 19). The second observation is that these highly questionable verses include our snake handling promise, including the promise such handlers will have special powers to heal sick folks.

It appears reasonable to question whether Mr. Coots sole authority for his Christian snake-handling beliefs, for his God-inspired way to demonstrate his faith, shouldn’t even be included in the Bible. Of course, this assumes the Bible, without these verses is the inerrant, infallible word of God. I wanted show it here but it doesn’t take much research to conclude Mark didn’t write the book of Mark. The author or authors are anonymous. But, we’ll leave that alone for now.

It seems our first draft raised some serious issues, none of which will likely be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction, especially to folks like Jamie Coots.

But, what about you? Will you stake your life on Rick Warren’s Bible? Believing God created and ordained you for a specific purpose in this life? Believing God that you’ll come to no harm handling those diamondback rattlers?

Or, is it more likely that if you do lean toward trusting in Warren’s Bible, you’ll at least ignore Mark 16:18 and cherry pick other verses to decide what you believe?

Ending thoughts. Why didn’t earlier manuscripts include verses 9-20? And, was Jamie Coots more likely to become a snake-handling Christian because of his ancestors (recall, both his father and grandfather were snake-handlers)? If so, does this indicate where we are born and to what parents and what they believe may be the primary reason we believe as we do.

Finally, can writing help us make better choices? Recall my new tag line: Writing is a tool for thinking, for discovering the truth obscured by a cluttered, unquestioning, and gullible mind.

Want a life with fewer snakes? Then, write to life.

For additional insight into Mark 16, read David Madison’s article, The Colossal Embarrassment of Mark 16.