Here’s the link to this article.

By David Madison at 5/12/2023

Deceptive translators don’t want readers to see the problems

There has been a meme floating about on the Internet: “If you ever feel worthless, remember, there are people with theology degrees.” These degrees are granted by a huge variety of religious schools, ranging from fundamentalist Protestant to Vatican-loyal Catholic. So among those holding these degrees—what else would we expect?—there is substantial disagreement regarding what god is like, how he/she/it expects people to behave, how he/she/it wants to be worshipped. This is one of the reasons Christianity has splintered into thousands of quarreling brands.

This confusion and strife can be traced to many sources (e.g., personality conflicts, egos, desire for power and control), but the Bible must take a large share of the blame. It is a deeply flawed document that shows no evidence whatever of divine inspiration: it contains so many contradictions, so much incoherence and bad theology. Thus the irony that the Bible itself—carefully read, that is—has destroyed faith for so many people. Mark Twain argued that the “best cure for Christianity is reading the Bible.” Andrew Seidel has pointed out that “the road to atheism is littered with Bibles that have been read cover to cover.”

Even a casual reading of the Bible can be shocking: “God so loved the world,” yet he got so mad at humans that he destroyed all human and animal life—except for the crowd on Noah’s boat. Jesus suggested that people should forgive seventy-times seven, yet assured his disciples that any village that did not welcome their preaching would be destroyed—and that hatred of family was a requirement for following him. This is what I mean by incoherence and bad theology. Anyone with common sense can figure it out.

These are items that are visible on the surface, and it gets worse; a closer examination reveals deeper problems. Devout Bible scholars have been aware for a long time that this is the case, and secular scholars don’t hesitate to expose the ways—unnoticed by the laity—in which the Bible itself destroys the faith that so many hold dear. On 1 May 2023, an article written by John Loftus was published on The Secular Web: Does God Exist? A Definitive Biblical Case. This is a must read. Bookmark the link for future reference. I printed the article to go in a binder of important essays. If you can manage to get Christian family and friends to do some homework on the Bible, this piece should be included.

Loftus invites his readers to see what is actually there in the Bible:

“What is almost always overlooked in debating the existence of the theistic god is that such a divine being has had a complex evolution over the centuries from Elohim, to Yahweh, to Jesus, and then to the god of the philosophers, without asking if the original gods had any merit…If believers really understood the Bible, they wouldn’t believe in any of these gods.”

Theologians and apologists, priests and preachers, have worked so hard over the centuries to clean up the god(s) that we find in the Bible, so that the faith today—that so many people are comfortable embracing—has a noble, positive flavor. If only the devout would bother to think carefully about their most common, cherished Bible texts. For example: “Our father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name.” Just what is god’s name? An easy answer would be, “Well, Jesus, of course.” But before Jesus, what was it? As Loftus mentions, one of them was Elohim, but pious translators sense their god having a name might make it look like he was just one of many of the pagan gods. And that was exactly the case, as Loftus notes: “When we take the Bible seriously, we discover a significant but unsuccessful cover-up about the gods that we find in the Bible, who evolved over the centuries through polytheism to henotheism to monotheism.”

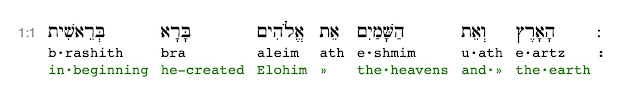

When I printed the Loftus essay, it came to twenty pages, seven of which are about Elohim—and most of this content never comes to the attention of devout laypeople. Loftus offers a careful analysis of the first two verses of Genesis 1, which are commonly translated something like this:

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was without form and void, and darkness covered the surface of the abyss, and the Spirit of God was moving over the waters.”

He points out that this is a more accurate rendering:

“Elohim made the skies and dry land, beginning with land that was without form and void, with darkness covering the surface of the chaos, and the wind of Elohim hovering over the waters,” while noting that “the original grammar is a bit difficult to translate. If nothing else, consider this a slightly interpretive translation using corrected wording.”

Loftus notes seven elements of this text that are commonly misunderstood, e.g., there is nothing here about the beginning of time, or creation out of nothing. Nor is the claim by contemporary theologians that an all-powerful cosmic god did the deed. Believers want to assume this was the case, and translators cooperate in promoting this deception, i.e., “In the beginning, God…” But the text says that Elohim was the initiator of this drama.

Just who was this Elohim? “The Hebrew word Elohim is derived from the name of the Canaanite god El, a shortened version of which is El Elyon, or ‘God Most High.’” Well, there, don’t you have the grand god Christians want? No, far from it: “El was the head of the Canaanite pantheon of gods.” Loftus quotes scholar Mark S. Smith:

“Archaeological data in the Iron I age suggests that the Israelite culture largely overlapped with and derived from Canaanite culture… In short, Israelite culture was largely Canaanite in nature.” (The Early History of God: Yahweh and Other Deities of Ancient Israel, 2002, pp. 6-7.)

The influence of Elohim-belief is reflected in so many of the names familiar to us in the Old Testament, e.g., Bethel, Michael, Daniel, and even Israel.

Elohim the tribal deity was imagined as we would expect of ancient writers who had no understanding whatever of the Cosmos. So it is silly to read the god imagined by modern believers into the Genesis story. Loftus describes the naïveté of these ancient theologians:

“Elohim showed no awareness of dinosaurs, nor the fact that the history of evolution has shown that 99.9% of all species have gone extinct, since evolution produces a lot of dead ends on its way to producing species that survive. Imagine that! On every day in Genesis 1 the supposed creator god Elohim knows nothing about the universe! … There is no excuse for a real creator to utterly fail a basic science class…There is no excuse for a real creator to mislead his creatures about something so important, which would lead generations of scientifically literate people away from the Christian religious faith and into damnation.”

Do things get any better with the other tribal deity who plays a major role in the Old Testament, namely Yahweh? Devout folks today can be forgiven if, when asked what god’s name is, they fail to answer, Yahweh. One of the most famous—and annoying—Christian cults proudly labels itself Jehovah’s Witnesses. That is, they know god’s name, as adjusted in English translation. Ancient Hebrew was written without vowels, and some of the consonants were flexible. Hence YHWH could also be JHVH. Plug in different vowels, and it becomes Jehovah instead of Yahweh. Even so, most of the devout—outside the Witness cult—wouldn’t right way agree that god’s name is Jehovah, let alone Yahweh.

One of the reasons for this, again, is that translators are eager to cover up the tribal god’s name, as Loftus points out:

“In the Old Testament, whenever you come across ‘the Lord Our God,’ or ‘the Lord God,’ or even ‘Lord,’ Christian translators have hidden the truth behind those words. It’s ‘Yahweh’ or ‘Yahweh your god.’” It’s easy to spot this coverup in the Revised Standard Version, which renders Yahweh as LORD, i.e., all capital letters. The ancient theologians who cobbled together the Old Testament were happy to put stories about Elohim right beside stories about Yahweh, e.g. the two creation stories in Genesis.

Loftus devotes a full eight pages in this essay to Yahweh, making quite clear that this was indeed an inferior tribal deity. He presents four aspects of Yahweh that qualify him as a moral monster, especially his behavior in the story of Job:

“In this story Yahweh lives in a separate palace in the sky and acts like a petty narcissistic king who would treat his subjects terribly simply because he could do so, just like any other despotic Mediterranean king they knew. Job was a pawn who was tortured for the pleasure of Yahweh and other sons of Elohim. At the end Yahweh doesn’t reveal why Job suffered, just that Job wasn’t capable of understanding why, so he was faulted for demanding an answer from the Almighty.”

Loftus also describes Yahweh’s guilt in terms of genocide, slavery, and child sacrifice—and limited power. Translators should be especially ashamed of labelling this deity LORD God: far from being omnipotent, its inferior status is obvious: “The LORD was with Judah, and he took possession of the hill country but could not drive out the inhabitants of the plain, because they had chariots of iron” (Judges 1:19).

Loftus is right: “Imagine that! An all-powerful god cannot defeat men in iron chariots! What could he do against tanks and fighter jets?”

In the final pages of the essay Loftus addresses the issue of Jesus as god. He had pointed out that Yahweh was depicted as having a body (in the Genesis story of the Garden of Eden, in his meetings with Moses), but the ultimate god-in-bodily-form would have to be Jesus. But the utter moral failures of Yahweh should encourage even the devout to admit, “No, that tribal god didn’t really exist.” But Loftus notes the devastating implications for the Jesus story:

“If the embodied moral monster Yahweh doesn’t exist, then the embodied god Jesus depicted in the Gospels doesn’t exist, either, since he’s believed to be the son of Yahweh, a part of the Trinity, and in complete agreement with everything that Yahweh said and did. That should be the end of it.”

This is not necessarily to say that Jesus as an actual historical person didn’t exist—although there are serious arguments that cause us to doubt it. But Loftus is saying that Jesus as a god is based so thoroughly on Yahweh the flawed tribal deity; hence the divine nature of Jesus can’t be taken seriously. He also notes that Justin Martyr, “the grandfather of the entire tradition of Christian apologetics,” sought to bolster the case for divine Jesus by arguing that he was like others who came before him:

“When we say that the Word, who is the first-birth of God, was produced without sexual union, and that He, Jesus Christ, our Teacher, was crucified and died, and rose again, and ascended into heaven, we propound nothing new from what you believe regarding those whom you esteem sons of Zeus.”

Loftus notes Richard Miller’s summation of Justin Martyr’s approach: “Our new hero is just like your own, except ours is awesome, whereas yours are the deceptions of demons.” (Miller, Resurrection and Reception in Early Christianity, 2017) Sounds a lot like how Christians put down other brands of Christians!

In my article here last week, I argued that core Christian beliefs are a “clumsy blend of ancient superstitions, common miracle folklore, and magical thinking.” Christian theologians have worked so hard over the centuries to overcome this huge handicap. Their god must be the best, the ultimate—he must be an omni-god: all good, all powerful, all knowing. But these arguments plunge their faith into massive incoherence. Loftus notes that the “problem of horrendous suffering renders that god-concept extremely improbable to the point of refutation” (see his anthology, God and Horrendous Suffering). Their whole endeavor—creating the god of the philosophers—is a fool’s errand: “If theists think that an omni-everything God can legitimately be based on the Bible or its theology, they are fooling themselves. They are inventing their own versions of God, just like the ancient peoples in the Bible did.”

David Madison was a pastor in the Methodist Church for nine years, and has a PhD in Biblical Studies from Boston University. He is the author of two books, Ten Tough Problems in Christian Thought and Belief: a Minister-Turned-Atheist Shows Why You Should Ditch the Faith (2016; 2018 Foreword by John Loftus) and Ten Things Christians Wish Jesus Hadn’t Taught: And Other Reasons to Question His Words (2021). The Spanish translation of this book is also now available.

His YouTube channel is here. He has written for the Debunking Christianity Blog since 2016.

The Cure-for-Christianity Library©, now with more than 500 titles, is here. A brief video explanation of the Library is here.

by

by

by

by