Month: May 2023

Montaigne and the Double Meaning of Meditation

Here’s the link to this essay.

“There is no exercise that is either feeble or more strenuous … than that of conversing with one’s own thoughts.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

“We all have the same inner life,” beloved artist Agnes Martin said in a wonderful lost interview. “The difference lies in the recognition. The artist has to recognize what it is.” But in an age where we compulsively seek to optimize our productivity, the art of presence with and recognition of our inner lives, while infinitely more rewarding, is one fewer and fewer of us are able or willing to master. Of those who seek to cultivate it despite the cultural current, many turn to meditation. And yet meditation itself has an ambivalent history that reflects this tug-of-war between productivity and presence.

Among the timeless trove of musings collected in his Complete Essays (public library; public domain) is the following passage Michel de Montaigne penned sometime in the second half of the 16th century:

Meditation is a rich and powerful method of study for anyone who knows how to examine his mind, and to employ it vigorously. I would rather shape my soul than furnish it. There is no exercise that is either feeble or more strenuous, according to the nature of the mind concerned, than that of conversing with one’s own thoughts. The greatest men make it their vocation, “those for whom to live is to think.”

“Meditation,” here, is taken to mean “cerebration,” vigorous thinking — the same practice John Dewey addressed so eloquently a few centuries later in How We Think. This conflation, at first glance, seems rather antithetical to today’s notion of meditation — a practice often mistakenly interpreted by non-practitioners as non-thinking, an emptying of one’s mind, a cultivation of cognitive passivity. In reality, however, meditation requires an active, mindful presence, a bearing witness to one’s inner experience as it unfolds. In that regard, despite the semantic evolution of the word itself, Montaigne’s actual practice of meditation was very much aligned with the modern concept and thus centuries ahead of his time, as were a great deal of his views.

In How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (public library) — that remarkable distillation of timeless lessons on the art of living from the godfather of “blogging,” explored more closely here — British philosophy scholar Sarah Bakewell points to Montaigne’s oft-quoted aphorism — “When I dance, I dance; when I sleep, I sleep.” — noting that he “achieved an almost Zen-like discipline” and remarking on his “ability to just be,” the essence of meditation:

It sounds so simple, put like this, but nothing is harder to do. This is why Zen masters spend a lifetime, or several lifetimes, learning it. Even then, according to traditional stories, they often manage it only after their teacher hits them with a big stick — the keisaku, used to remind meditators to pay full attention. Montaigne managed it after one fairly short lifetime, partly because he spent so much of that lifetime scribbling on paper with a very small stick… Observing the play of inner states is the writer’s job. Yet this was not a common notion before Montaigne, and his peculiarly restless, free-form way of doing it was entirely unknown.

Meditation, then, isn’t merely the product of solitude — that increasingly endangered art of learning how to be alone — but is also aided by an active record of one’s inward gaze, the very practice that makes keeping a diary so spiritually and creatively beneficial, particularly for writers.

How to Live is revelational in its entirety, full of Montaigne’s timeless and ever-timely wisdom on the most central questions of leading a meaningful life.

Goddess Timeline

05/18/23 Biking & Listening

Biking is something else I both love and hate. It takes a lot of effort but does provide good exercise and most days over an hour to listen to a good book or podcast. I especially like having ridden.

Here’s my bike, a Rockhopper by Specialized. I purchased it November 2021 from Venture Out in Guntersville; Mike is top notch! So is the bike, and the ‘old’ man seat I salvaged from an old Walmart bike.

Here’s a link to today’s bike ride. This is my pistol ride.

Here’s a few photos taken along my route:

Here’s what I’m listening to: It Ends With Us, by Colleen Hoover

Amazon abstract:

In this “brave and heartbreaking novel that digs its claws into you and doesn’t let go, long after you’ve finished it” (Anna Todd, New York Times bestselling author) from the #1 New York Times bestselling author of All Your Perfects, a workaholic with a too-good-to-be-true romance can’t stop thinking about her first love.

Lily hasn’t always had it easy, but that’s never stopped her from working hard for the life she wants. She’s come a long way from the small town where she grew up—she graduated from college, moved to Boston, and started her own business. And when she feels a spark with a gorgeous neurosurgeon named Ryle Kincaid, everything in Lily’s life seems too good to be true.

Ryle is assertive, stubborn, maybe even a little arrogant. He’s also sensitive, brilliant, and has a total soft spot for Lily. And the way he looks in scrubs certainly doesn’t hurt. Lily can’t get him out of her head. But Ryle’s complete aversion to relationships is disturbing. Even as Lily finds herself becoming the exception to his “no dating” rule, she can’t help but wonder what made him that way in the first place.

As questions about her new relationship overwhelm her, so do thoughts of Atlas Corrigan—her first love and a link to the past she left behind. He was her kindred spirit, her protector. When Atlas suddenly reappears, everything Lily has built with Ryle is threatened.

An honest, evocative, and tender novel, It Ends with Us is “a glorious and touching read, a forever keeper. The kind of book that gets handed down” (USA TODAY).

Science of Genesis Paradise Lost – Part 9 Science of Genesis Paradise Lost – Part 9 ‘Dem Soft Bones (feat. Dr. Mary Schweitzer)

Sam Harris on the Paradox of Meditation and How to Stretch Our Capacity for Everyday Self-Transcendence

Here’s the link to this essay.

“Positive emotions, such as compassion and patience, are teachable skills; and the way we think directly influences our experience of the world.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

Montaigne believed that meditation is the finest exercise of one’s mind and David Lynch uses it as an anchor of his creative integrity. Over the centuries, the ancient Eastern practice has had a variety of exports and permutations in the West, but at no point has it been more vital to our sanity and psychoemotional survival than amidst our current epidemic of hurrying and cult of productivity. It is remarkable how much we, as a culture, invest in the fitness of the body and how little, by and large, in the fitness of the spirit and the psyche — which is essentially what meditation provides.

In Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion (public library), neuroscientist and philosopher Sam Harris argued that cultivating the art of presence is our greatest gateway to true happiness. After his extensive, decades-long empirical romp through the world’s major religious traditions and humanity’s most potent psychedelic substances, Harris returns again and again to meditation as the holy grail of self-transcendence, the single most promising practice for slicing through the illusion of the ego to reveal what Jack Kerouac so memorably called “the Golden Eternity.”

Harris writes:

Although the insights we can have in meditation tell us nothing about the origins of the universe, they do confirm some well-established truths about the human mind: Our conventional sense of self is an illusion; positive emotions, such as compassion and patience, are teachable skills; and the way we think directly influences our experience of the world.

We know that the self is a social construct and the dissolution of its illusion, Harris argues, is the most valuable gift of meditation:

The conventional sense of self is an illusion [and] spirituality largely consists in realizing this, moment to moment. There are logical and scientific reasons to accept this claim, but recognizing it to be true is not a matter of understanding these reasons. Like many illusions, the sense of self disappears when closely examined, and this is done through the practice of meditation.

[…]

The feeling that we call “I” seems to define our point of view in every moment, and it also provides an anchor for popular beliefs about souls and freedom of will. And yet this feeling, however imperturbable it may appear at present, can be altered, interrupted, or entirely abolished.

Such abolition may seem unnerving in the context of personal identity, something to which we are invariably attached, but as soon as we begin to understand just how mutable that identity is, dissolving the self illusion becomes not a punishing negation of free will but a promise of freedom. Harris writes:

The self that does not survive scrutiny is the subject of experience in each present moment — the feeling of being a thinker of thoughts inside one’s head, the sense of being an owner or inhabitant of a physical body, which this false self seems to appropriate as a kind of vehicle. Even if you don’t believe such a homunculus exists — perhaps because you believe, on the basis of science, that you are identical to your body and brain rather than a ghostly resident therein — you almost certainly feel like an internal self in almost every waking moment. And yet, however one looks for it, this self is nowhere to be found. It cannot be seen amid the particulars of experience, and it cannot be seen when experience itself is viewed as a totality. However, its absence can be found — and when it is, the feeling of being a self disappears.

And yet, and yet, this is where the essential paradox of meditation arises — if meditation is about cultivating the capacity to accept the present moment exactly as it is, then the notion of a meditation practice or of mindfulness training, which implies progress toward a future goal, seems at odds with the very concept of such pure presence. Harris captures this elegantly:

We wouldn’t attempt to meditate, or engage in any other contemplative practice, if we didn’t feel that something about our experience needed to be improved. But here lies one of the central paradoxes of spiritual life, because this very feeling of dissatisfaction causes us to overlook the intrinsic freedom of consciousness in the present. As we have seen, there are good reasons to believe that adopting a practice like meditation can lead to positive changes in one’s life. But the deepest goal of spirituality is freedom from the illusion of the self — and to seek such freedom, as though it were a future state to be attained through effort, is to reinforce the chains of one’s apparent bondage in each moment.

The solution to the paradox, Harris suggests, is in approaching mindfulness not as a compulsively productive practice of self-improvement — there is the “self” creeping up again — but as a state of active presence with everyday life:

The ultimate wisdom of enlightenment, whatever it is, cannot be a matter of having fleeting experiences. The goal of meditation is to uncover a form of well-being that is inherent to the nature of our minds. It must, therefore, be available in the context of ordinary sights, sounds, sensations, and even thoughts. Peak experiences are fine, but real freedom must be coincident with normal waking life.

He cautions against treating meditation as another to-do item:

Those who begin to practice in the spirit of gradualism often assume that the goal of self-transcendence is far away, and they may spend years overlooking the very freedom that they yearn to realize.

Reflecting on his training with the Burmese spiritual master Sayadaw U Pandita, who teaches meditation as an “explicitly goal-oriented” practice — mindfulness is approached not as freedom from the self illusion in the present moment but as a means of attaining the “cessation” of that illusion in the future — Harris writes:

[This approach] encourages confusion at the outset regarding the nature of the problem one is trying to solve. It is true, however, that striving toward the distant goal of enlightenment (as well as the nearer goal of cessation) can lead one to practice with an intensity that might otherwise be difficult to achieve. I never made more effort than I did when practicing under U Pandita. But most of this effort arose from the very illusion of bondage to the self that I was seeking to overcome. The model of this practice is that one must climb the mountain so that freedom can be found at the top. But the self is already an illusion, and that truth can be glimpsed directly, at the mountain’s base or anywhere else along the path. One can then return to this insight, again and again, as one’s sole method of meditation — thereby arriving at the goal in each moment of actual practice.

Despite the paradoxes of the practice, however, Harris considers it our most promising access point to a fulfilling spiritual life:

It is very difficult to imagine someone’s not being able to see her reflection in a window even after years of looking — but that is what happens when a person begins most forms of spiritual practice. Most techniques of meditation are, in essence, elaborate ways for looking through the window in the hope that if one only sees the world in greater detail, an image of one’s true face will eventually appear. Imagine a teaching like this: If you just focus on the trees swaying outside the window without distraction, you will see your true face. Undoubtedly, such an instruction would be an obstacle to seeing what could otherwise be seen directly. Almost everything that has been said or written about spiritual practice, even most of the teachings one finds in Buddhism, directs a person’s gaze to the world beyond the glass, thereby confusing matters from the very beginning.

But one must start somewhere. And the truth is that most people are simply too distracted by their thoughts to have the selflessness of consciousness pointed out directly. And even if they are ready to glimpse it, they are unlikely to understand its significance.

Harris reframes the paradox with an admonition and an assurance:

Embracing the contents of consciousness in any moment is a very powerful way of training yourself to respond differently to adversity. However, it is important to distinguish between accepting unpleasant sensations and emotions as a strategy — while covertly hoping that they will go away — and truly accepting them as transitory appearances in consciousness. Only the latter gesture opens the door to wisdom and lasting change. The paradox is that we can become wiser and more compassionate and live more fulfilling lives by refusing to be who we have tended to be in the past. But we must also relax, accepting things as they are in the present, as we strive to change ourselves.

[…]

Happiness and suffering, however extreme, are mental events. The mind depends upon the body, and the body upon the world, but everything good or bad that happens in your life must appear in consciousness to matter. This fact offers ample opportunity to make the best of bad situations — changing your perception of the world is often as good as changing the world — but it also allows a person to be miserable even when all the material and social conditions for happiness have been met. During the normal course of events, your mind will determine the quality of your life.

In a conversation with Tim Ferriss on the altogether excellent The Tim Ferriss Show, Harris argues that the mindfulness meditation cultivates — a quality of mind that allows you to pay attention to whatever arises without being lost in thought — is the most useful way to explore the phenomenon of self-transcendence “without believing anything on insufficient evidence.” He adds:

The human nervous system is plastic in a very important way — which means your experience of the world can be radically transformed. You are tending who you were yesterday by virtue of various habit patterns and physiological homeostasis and other things that are keeping you very recognizable to yourself, but it’s possible to have a very different experience… It’s possible to do it through a deliberate form of training, like meditation, and I think it’s crucial to do — because we all want to be as happy and as fulfilled and as free of pointless suffering as can possibly be. And all of our suffering, and all of our unhappiness, is a product of how our minds are in every moment. So if there’s a way to use the mind itself to improve one’s capacity for moment-to-moment wellbeing — which I’m convinced there is — then this should be potentially of interest to everybody.

Milton, it turns out, was not only philosophically but also neuropsychologically right when he penned his famous verse: “The mind is its own place, and in itself / Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven.”

If you are looking for a good place to start with meditation, or would like slow-burning fuel for your existing practice, I highly recommend Tara Brach, who has truly transformed my life — her teachings and guided meditations are available as a reliably excellent free podcast, and her four-part primer on meditation is indispensable for beginners. (If you are moved and enriched by her generously offered free teachings, consider making a donation — Brach’s work, like my own, is supported by direct patronage, and I am a proud monthly donor.)

Harris has also written about how to begin a meditation practice himself.

Waking Up, which you can sample further here, is a superb read in its entirety, quite possibly the best thing written on this ecosystem of spiritual subjects since Alan Watts’s treatise on the taboo against knowing who you really are.

Mr. Hume: Tear. Down. This. Wall. A Response to George Ellis’s Critique of My Defense of Moral Realism

Another great article by Michael Shermer. Download and read.

The Final Lecture

Here’s the link to this article. Definitely worth a read.

Ten lessons on living a good life and being resilient in the teeth of entropy, problems, setbacks & obstacles, aka normal life

MAY 16, 2023

For the past 12 years I have been a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University, where I have taught a course called Skepticism 101: How to Think Like a Scientist, examples for which I draw from over 30 years of publishing Skeptic magazine and directing the Skeptics Society. I lecture on causality and determining truth, Bayesian reasoning, Signal Detection Theory, the scientific method, rationality and irrationality, game theory, cognitive biases, cults, conspiracies, Holocaust denial, creationism, science and religion, and much more (you can watch some of the lectures that I recorded remotely during the pandemic here).

In the final minutes of the final lecture of my final semester at Chapman a student asked what practical lessons for life I might share with them. I offered as much as I could think of off the top of my head, but since I have researched and written a fair amount on this topic over the decades (and tried to apply these lessons to my own life) I thought I would deliver a final lecture here, not only for my students but for anyone who is interested in knowing what tools science and reason can provide for how to live a good life and how to deal with entropy, problems, setbacks and obstacles, aka normal life. I have kept this short and limited to ten lessons, but I plan to expand each of these into chapter-length lessons and add a number more (possibly for a book). Watch for those in this space as well as in eSkeptic and on my podcast. To that end, please consider becoming a paid subscriber below. All monies go to the Skeptics Society, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit educational organization.

Skeptic is a reader-supported publication. All monies go to the Skeptics Society, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Lesson 1. The First Law of Life

The Second Law of Thermodynamics is first law of life, namely to expend energy to survive and flourish. That sounds rather anodyne, so let me unpack that briefly here, then we will see how it applies to all the other lessons.

We are physical beings living in a physical universe governed by the laws of nature. One of the most fundamental of all the laws of nature is called the Second Law of Thermodynamics, sometimes called “entropy”, which holds that in a closed system energy dissipates, disorder increases, and things run down.

A hot cup of coffee, for example, will get cold if you don’t do anything to heat it up again. Why? Because heat is produced by all the jiggling of the water and coffee molecules in the cup, and since energy decreases and disorder increases, over time the molecules will jiggle less and the heat will dissipate into the environment, like the air above the cup or your hand holding the cup (which itself temporarily warms as the heat is transferred). In this case, a microwave oven to re-heat the coffee is your way of fighting back against entropy by putting energy into the cup. Of course, the energy to run the microwave comes from electricity generated by power plants, which you have to pay for each month, so there’s no free lunch in the universe!

Humans are open systems. We capture energy from food and convert it to power our muscles to move and push back against entropy, like making coffee, cleaning the house, going to work, and so forth. This is what I mean when I say that the Second Law of Thermodynamics is the First Law of Life. Your purpose in life is to expend energy to carve out pockets of order that lead to survival and flourishing.

Examples of entropy abound: metal rusts if you don’t maintain it. Weeds overrun gardens if you don’t weed them. Wood rots if you don’t paint it. Beds stay unmade and bedrooms get cluttered if you don’t make and clean them. Your body will grow weak and flabby if you don’t stress it regularly with exercise. Your mind becomes fuzzy and confused if you don’t challenge it to think. Friendships and relationships must be maintained through regular communication. An empty bank account is what happens if you don’t go to work and earn money. Poverty is what societies get if they do nothing productive.

Entropy is not a “force” per se, like gravity. It’s just what happens if energy isn’t put into the system. Think of a sandcastle: There are a near infinite number of ways that grains of sand can be configured into an amorphous blob that resembles nothing in particular, but with just the right amount of water mixed with the sand there are a limited number of ways that the grains can be congealed into structures that resemble castles. What happens if the sandcastle is not maintained? Wind and waves and dogs and children erode it back into a featureless glob. There are simply far more ways for sand to be unstructured than structured. Life consists of building sand castles and maintaining them.

This also explains why failures in life are so much more common than successes: there are simply more ways to fail than there are to succeed. And the higher you aim the more obstacles there are going to be for you to get there, and entropy will push back against you along the way. Remember that the next time you fail. Like sandcastles, failure is normal, success unusual.

Lesson 2. To Thine Own Self Be True

In William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, the character Polonius says:

“This above all: to thine own self be true,

And it must follow, as the night the day.

Thou canst not then be false to any man.”

To thine own self be true. What does this mean, exactly? Let’s begin with what philosophers call the Law of Identity: A is A, which means that each thing is identical with itself. The 15th century philosopher Nicholas of Cusa explained it this way: “there cannot be several things exactly the same, for in that case there would not be several things, but the same thing itself.”

Being true to yourself means recognizing and acknowledging that A is A, that you are you and not someone else. To try to be something that you are not, or to pretend to be someone else, is a violation of the Law of Identity: A cannot be non-A.

A is A means discovering who you are, your temperament and personality, your intelligence and abilities, your needs and wants, your loves and interests, what you believe and stand for, where you want to go and how you want to get there, and what matters most to you. Thine own self is your A, which cannot also be non-A. The attempt to make A into non-A has caused countless problems, failures, and heartaches in peoples’ lives.

How do you figure out who you are? By testing yourself, by trying new things, by meeting new people, by exploring, traveling, and reading, by trying different jobs and considering different careers. In time you will discover that most things you try, you will not be good at, but out of all those failures will emerge a handful of things that you are good at, a few people whom you are drawn to, and slowly the real you will emerge and thine own true self will come into focus.

Lesson 3. Be Antifragile

If the purpose of life is to survive and flourish in the teeth of entropy pushing back against everything you do, then you need to be antifragile, a word coined by the risk analyst Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his 2012 book of that title, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder, on how to live in a world that is unpredictable and chaotic, and how to thrive during times of stress and even disaster.

Antifragile means growing and prospering from randomness, uncertainty, opacity, and disorder, and benefitting from a variety of shocks. Here’s how my psychologist friend and colleague Jonathan Haidt applies the concept of antifragility to raising children:

Bone is anti-fragile. If you treat it gently, it will get brittle and break. Bone actually needs to get banged around to toughen up. And so do children … they need to have a lot of unsupervised time, to get in over their heads and get themselves out.

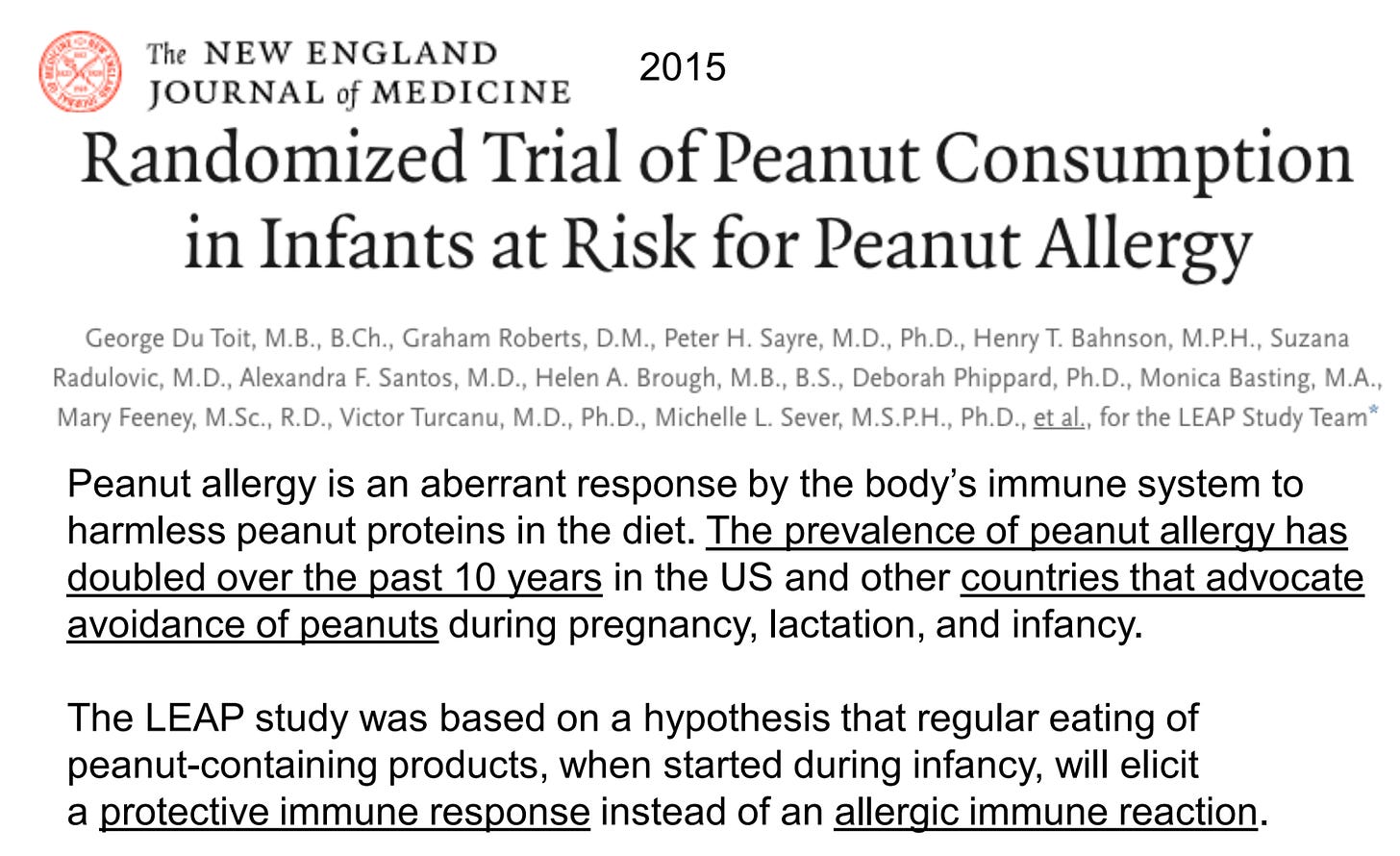

For example, peanut allergies were once extremely rare. A mid-1990s study found that only 4 out of 1,000 children under the age of eight had a peanut allergy. A 2008 study by the same researchers, however, found that the rate had skyrocketed by 350 percent to 14 per 1,000. Why? Because parents and teachers had protected children from exposure to peanuts. The lesson is clear: immune systems become antifragile by exposure to environmental stressors, and so too do our minds and bodies to the stressors of daily life.

One solution to this problem may be found in an old saying: “Prepare the child for the road, not the road for the child.” Other idioms capture the principle behind the lesson of antifragility: “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” Nietzsche famously said. “Tough times don’t last but tough people do,” my mother often told me. Here is what I wrote one of my students when she was going through a particularly difficult time:

No matter who you reach out to, ultimately it will come down to you and how you respond to your issues. There’s only so much other people can do. In the end, you have to help yourself. Whatever has happened in your life, you can’t do anything about that now as it is in the past and is out of your control. What is in your control is how you respond to it, whatever the “it” is, starting by deciding today that you are not going to let yourself be a victim any longer. It has to stop.

Ultimately only you can make it stop. Psychologists, family, and friends can only do so much. You must dig deep inside yourself and call up reserves you didn’t know you had, and from there rebuild your life, day by day, hour by hour, until it no longer is holding you back from realizing your full potential. What does not kill you makes you stronger. Whatever happened, it didn’t kill you. You are alive. You are engaged in the world. You are working on assignments. You will grow stronger with every accomplishment.

The current craze of overprotecting students from anything that makes them uncomfortable, including ideas that may challenge them, is making them weaker, not stronger, fragile, not antifragile.

Lesson 4. Be Self-Disciplined Because Action is Character

As the name implies, discipline comes from within the self. You are the architect of your life. You are responsible for what you do. So do it. How? Change your behavior and your cognition will follow. Change your habits and your thoughts will follow.

Everyone is looking for a hack, an easy way around the self-discipline problem. There is no hack and no way around being self-disciplined. External motivations, like motivating yourself with rewards for changing your habits, will not last. The motivation must eventually come from within. Internal motivation is the key to self-discipline.

You want to stop eating sugar and unhealthy food? Stop eating sugar and unhealthy food! Where? Here. When? Now. Self-discipline happens here and now. Stop eating bad food and start eating good food…here and now. Just do it.

Toward the end of his life the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote that “action is character,” by which he meant that what you do is who you are. Cognitive psychologists call this “embodied cognition”, in which action becomes character. My friend the science writer Amy Alkon wrote a book about this, colorfully titled Unfuckology: A Field Guide to Living with Guts and Confidence, with a chapter title that perfectly captures this principle: “The Mind is Bigger Than the Brain.” Here’s how Amy explains the principle in her humorous way:

Embodied cognition research shows that who you are is not just a product of your brain. It’s also in your breathing, your gut, the way you stand, the way you speak, and, while you’re speaking, whether you make eye contact or dart your eyes like you’re about to bolt under a car like a cat.

By acting and behaving a new way, you push out of your mind the old ways of being that you want to change. You are what you do. So act the way you want to feel. Be the person you want to be by acting like that person. As the Buddha counseled:

Your worst enemy cannot harm you as much as your own thoughts, unguarded. But once mastered, no one can help you as much.

Lesson 5. Don’t be a Victim

In their 2018 book The Rise of Victimhood Culture: Microaggressions, Safe Spaces, and the New Culture Wars, the sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning document how Western society has transitioned from an honor culture to a dignity culture and now is shifting into a victimhood culture.

In a culture of honor, each person has to earn honor and, unable to tolerate a slight, takes action himself. The big advance in Western society was to let the law handle serious offenses and ignore the inevitable minor ones—what sociologists call the culture of dignity, which reigned in the 20th century. It allows diversity to flourish because different people can live near each other without killing each other. As such, a culture of honor leads to autonomy, independence, self-reliance, confidence, courage, and strength of character.

The past quarter century, however, has seen the rise of a victimhood culture, where people are hypersensitive to slights as in the honor culture, but they don’t take care of it themselves. Instead they appeal to a third party to punish for them. A culture of victimhood leads people to divide the world into good and bad classes—victims and oppressors. As such, a culture of victimhood makes one weak, dependent, timid, afraid, and lacking courage and character.

Yes, any of us can be victims, but how you handle it matters. In a victimhood culture the primary way to gain status is to either be a victim or to condemn alleged perpetrators against victims, leading to an accelerating search for both. An Oxford student explained what happened to her after she joined a campus feminist group named Cuntry Living and started reading their literature on misogyny and patriarchy:

Along with all of this, my view of women changed. I stopped thinking about empowerment and started to see women as vulnerable, mistreated victims. I came to see women as physically fragile, delicate, butterfly-like creatures struggling in the cruel net of patriarchy. I began to see male entitlement everywhere.

As a result she became fearful and timid, afraid even to go out to socialize:

Feminism had not empowered me to take on the world—it had not made me stronger, fiercer or tougher. Even leaving the house became a minefield. What if a man whistled at me? What if someone looked me up and down? How was I supposed to deal with that? This fearmongering had turned me into a timid, stay-at-home, emotionally fragile bore.

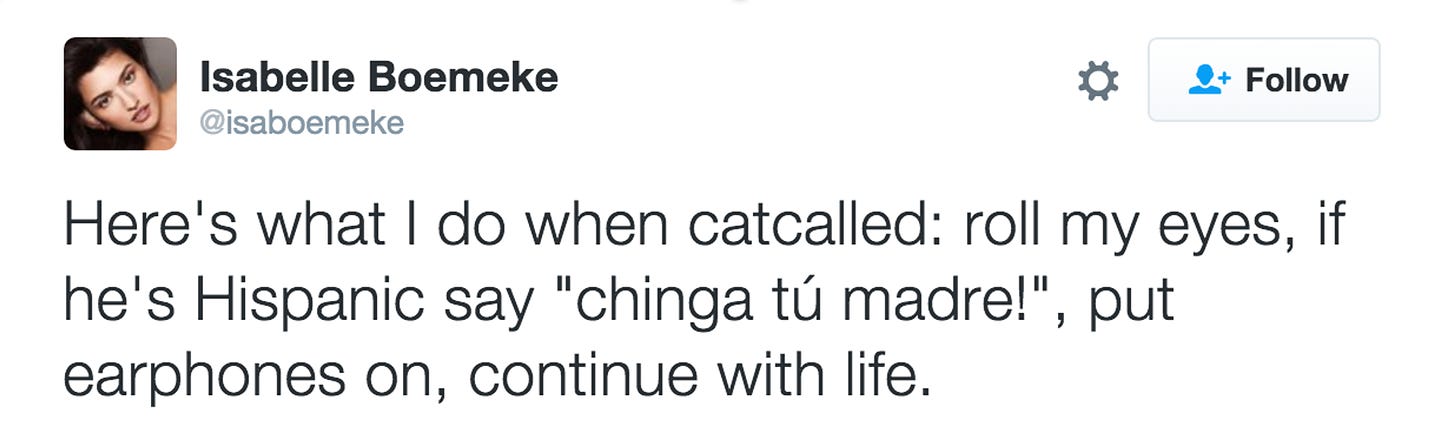

Here is an antifragile way to deal with misogyny and patriarchy, from the model and pro-nuclear energy activist Isabelle Boemke:

If your Spanish is rusty a biblical metonymy may be found in the command to “go forth and multiply” (with your mother).

So stop with the safe spaces, trigger warnings, microaggressions, and especially the deplatforming and cancelation of speakers who may cause students to rethink their beliefs—you know, what colleges and universities were designed to do. It is turning young adults into fragile snowflakes instead of antifragile warriors.

Lesson 6. Don’t Eat the Marshmallow

When video of Admiral William H. McRaven’s 2014 commencement address at the University of Texas at Austin was posted online, the speech went viral. Millions of viewers will remember the core message summed up in his memorable line: “If you want to change the world, start off by making your bed.” The Navy SEAL veteran explained the psychology behind such a simple task:

If you make your bed every morning you will have accomplished the first task of the day. It will give you a small sense of pride and it will encourage you to do another task and another and another. By the end of the day, that one task completed will have turned into many tasks completed. Making your bed will also reinforce the fact that little things in life matter. If you can’t do the little things right, you will never do the big things right. And, if by chance you have a miserable day, you will come home to a bed that is made—that you made—and a made bed gives you encouragement that tomorrow will be better.

Admiral McRaven’s “life lessons” in his speech are, in fact, variations on a theme explored by the legendary psychologist Walter Mischel in his 2014 book The Marshmallow Test. The key to being a successful Navy SEAL—or anything else in life—is summed up in the book’s subtitle, Mastering Self-Control. Mischel begins by describing how, in the late 1960s, he and his colleagues devised a straightforward experiment to measure self-control at the Bing Nursery School at Stanford University.

In its simplest form, children between the ages of 4 and 6 were given a choice between one marshmallow now or two marshmallows if they waited 15 minutes. Some kids ate the marshmallow right away, but most engaged in unintentionally hilarious attempts to overcome temptation. They averted their gaze, covered their eyes, squirmed in their seats, or sang to themselves. They made grimacing faces, tugged at their ponytails, picked up the marshmallow and pretended to take a bite. They sniffed it, pushed it away from them, covered it up. If paired with a partner, they engaged in dialogue about how they could work together to reach the goal of doubling their pleasure.

In 2006, Professor Mischel published a new paper in the prestigious journal Psychological Science. The researchers did a follow-up study with the students they had tested 40 years before, examining the type of adults they had grown into. They found that the children who were able to delay gratification had higher SAT scores entering college, higher grade-point averages at the end of college, and they made more money after college. Perhaps not surprisingly, they also tended to have a lower body-mass index. That is, they were less likely to have a weight problem.

So, not eating the marshmallow is good for both your body and your mind. And all of life is a series of marshmallow tests.

Lesson 7: Directing Your Future Self

In an episode of the hit animated television series The Simpsons, Marge warns her husband that he might regret the drinking binge he’s about to go on, to which Homer replies: “That’s a problem for future Homer. Man, I don’t envy that guy.”

All of us, in fact, have future selves. Or, more accurately, there is no fixed self, but rather an ever-changing self, and the fact that we can project ourselves into the future means we can not only anticipate how our future selves might act, we can take measures today to alter how our future selves behave.

In the field of behavioral economics this problem of the future self is called future discounting, or myopic (nearsighted) discounting, and research shows that most of us discount the future too steeply, for example, electing to spend too much now instead of saving some for later. People are notoriously bad at long-term investing, as well as selecting smart retirement plans. The reason is that in the world we evolved in, and in all of human history until recently, life was, in the words of the political theorist Thomas Hobbes, “nasty, brutish, and short.” Why save for a fabulous 75th birthday party when the odds were high that you’d be dead by 50?

For most of our ancestors, a bird in the hand was worth two in the bush. In that world, it was better to eat one marshmallow now rather than risk the promised two marshmallows later that might be purloined or otherwise lost. A bumper sticker captures the temptation psychology: “Life is short. Eat dessert first.”

In today’s world, however, there is a good chance you will live a long life, so there is some justification to figuring out how to delay gratification, save for the future, plan for retirement, and expect your future self to be around for awhile.

The key here is projecting your current self into the future, asking yourself now what you want to happen then, and set up conditions today that you know will take effect later when your future self may not be trusted with doing the right thing.

That is, you don’t want to be Homer and say of your future self “man, I don’t envy that guy.”

Lesson 8: Be Your Own Financial Advisor

The comedian Woody Allen once joked, “It is better to be rich than it is to be poor…if only for financial reasons.” Well, yes, it is, and those financial reasons are not trivial.

Money may not be able to buy you love, happiness, or meaningfulness, but it sure can make life more comfortable and, more importantly, it can increase your opportunities for finding love, happiness and meaningfulness. How?

First, if you’re living on the margin—that is, your income barely covers your expenses and you have next to nothing left over for additional consumption or investment—your opportunities for doing anything else, from vacations to hobbies to retirement, are reduced to next to nothing.

Second, money buys you time, and that time can be put to use to make more money, as well as enjoy life by enriching it with additional opportunities for both business and pleasure.

Third, money buys a better life: better food, better clothes, better homes, better education, better transportation, better travel, better recreation, and better retirement.

How do you make money? Investments in real estate or the stock market (or both). I recommend a book called The Gone Fishin’ Portfolio by a financial advisor named Alex Green, who subsequently became a friend of mine. What Alex demonstrates is that no one can consistently beat the market. You may hear about people who do—for example, fund managers like Bill Miller, who in 2006 was declared by CNNMoney.com to be “The Greatest Money Manager of our Time” because he beat the S&P 500 stock index 15 years in a row.

But as my science writer friend Leonard Mlodinow calculated in his book The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives, there are over 6,000 fund managers in the U.S., and so if you do a simple coin-flip calculation of the odds that someone in that cohort of 6,000 fund managers would beat the S&P 500 15 years in a row, it turns out to be .75, or 3 out of 4. As Len says, the CNNMoney headline should have read “Expected 15-Year Run Finally Occurs: Bill Miller Lucky Beneficiary.” And, wouldn’t you know it, in the two years after Miller’s 15-year streak, the story read: “the market handily pulverized him.”

When Alex Green says to “go fishin” what he means is that you should not try to be the next Bill Miller. Why? Because only after the fact can we pick out the winners. Instead, you should pick stocks in companies with a solid track record—or, even better, invest in mutual funds tied to, for example, the S&P 500—and then, well, go fishing; that is, leave your investments alone. For example, Green calculates that if you invested $10,000 in 1990 in a mutual fund tied to the entire S&P 500 and then went fishing, 20 years later you would have $90,000, not counting dividend reinvestment, which would push you well over the $100,000 figure.

By contrast, if you tried to be actively involved in trading—buying and selling stocks and trying to anticipate what the market would do—you risk missing the biggest increases in that 20-year block. For example, if you miss just the 5 best days in that 20 years, your $90,000 account would plummet to $45,000. If you miss the 10 best days you’d end up with around $35,000. If you miss the best 25 days your $10,000 investment would only bring you only $19,000. And if you miss the best 50 days…you’d actually lose money.

Anyone can compute for you how much stocks have returned to investors in the past. No one can do that for the future. In the case of the S&P 500, since the 1920s it has returned an annualized average of around 10%. The returns for the NASDAQ, which is heavily loaded in tech stocks that have done so well the past 20 years, is significantly higher. Whichever fund you invest in, however, you should expect that your returns will not be significantly higher or lower than the long-term average, which in any block of time in a two-digit positive number. Here’s how Alex Green explains it:

History clearly demonstrates that no other asset class returns more than stocks over the long haul. Once you understand this—and accept the steep odds against timing the market—you’ve made the first step toward adopting an investment strategy that can generate high returns with an acceptable level of risk.

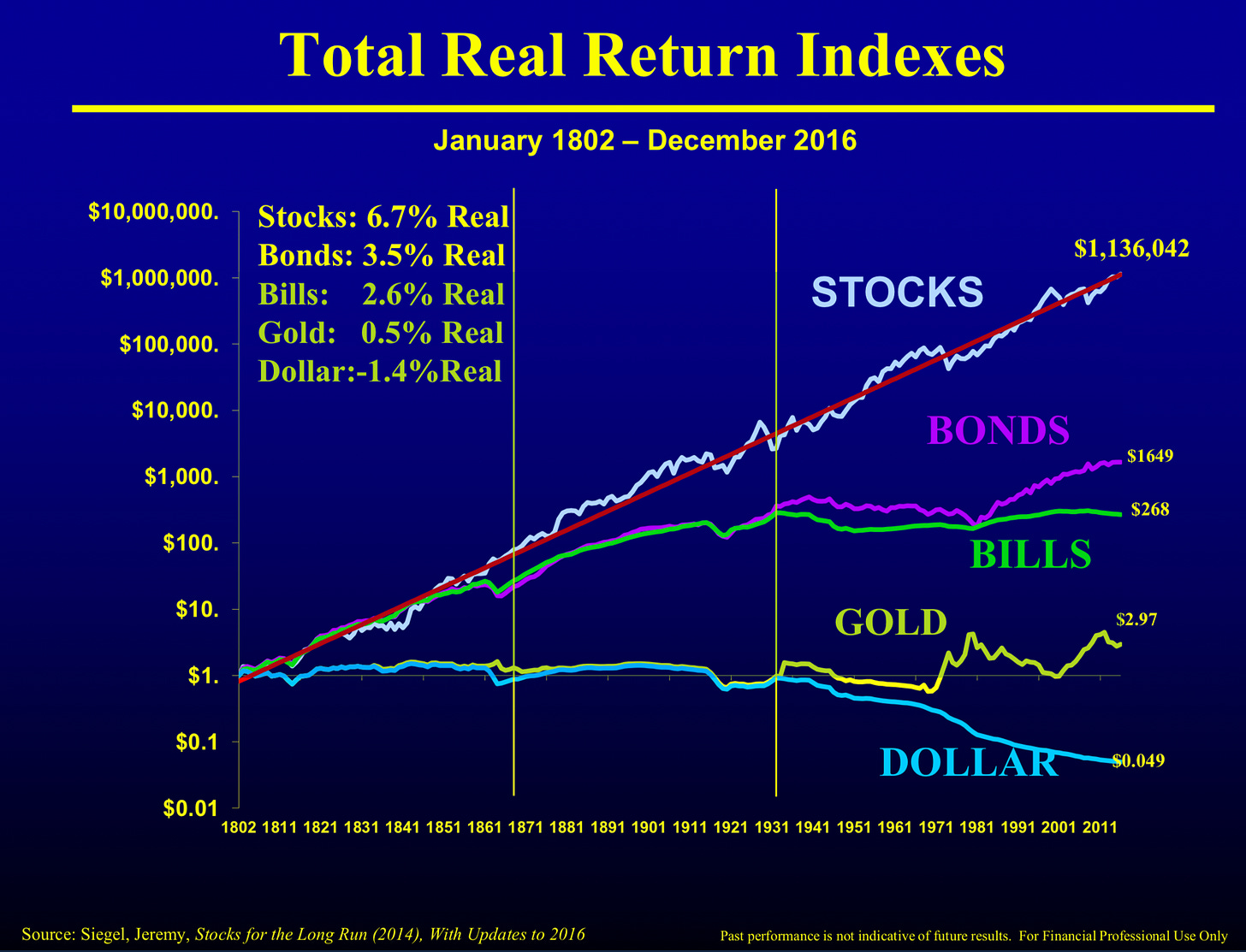

Here’s a chart showing the value of different assets over the very long run:

Lesson 9: Build Strong Social Networks

Diet and exercise are very important tools for living a long, healthy, and high-quality life, but believe it or not there’s something else you can do that produces even better results and it doesn’t require getting up at Zero Dark Thirty, doing push-ups, or eating kale. All you have to do is be sociable. Here are some comparisons of things you can do to lower your mortality risk based on the latest studies in longevity by scientists around the world:

- Exercise lowers mortality risk by 33%. A happy marriage lowers it by 49%.

- Eating 6 or more servings per day of fruits and vegetables lowers mortality risk by 26%. Having a large social network lowers it by 45%

- Eating 3 servings a day of whole grains lowers mortality risk by 23%. Feeling you have others you can count on for support lowers it by 35%.

- Eating a Mediterranean diet lowers mortality risk by 21%. Living with someone lowers it by 32%.

These numbers, and their implications for what you can do to improve your life, were compiled by the science journalist Marta Zaraska and published in her book Growing Young: How Friendship, Optimism, and Kindness can Help You Live to 100. Here are some of her suggestions of simple things you can do, all backed by scientific research:

- Engage in more physical contact with others: kiss your partner more often, hold hands with your kids, hug your friends, rub each other’s back, look others in the eyes.

- Prioritize your romantic relationship and really commit to it. Read books and articles on how to be a better partner. Avoid contempt, criticism, stonewalling, and defensiveness. Talk with your partner about good things that happen in your daily life. Try new and fun things together and have some fun.

- Invest in your friendships. Spend more time together, disclose your secrets, and don’t be afraid to ask for favors. When you’re with your partner or friends and family, put your phone away and focus on them.

- Be more extraverted by greeting staff in a store, calling a friend whom you haven’t talk to in awhile, try a new restaurant or bar or café where you will meet new people working there.

In Zaraska’s words, here’s the bottom line:

It’s time we recognize that improving our social lives and cultivating our minds can be at least as important for health and longevity as are diet and exercise. When you grow as a person, chances are, you will also grow young. To Michael Pollan’s famous statement, “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants,” I would add: “Be social, care for others, enjoy life.”

Lesson 10. Find Your Meaning and Purpose in Life

What, specifically, should you do to find meaning and purpose in life? Philosophers, theologians, and sages from spiritual traditions have been writing about this topic for millennia, and recently psychologists have undertaken scientific studies of people and what they do to find meaning and purpose in life. Here are some of their findings.

1. Love and family. The bonding and attachment to other people increases one’s circle of sentiments and a corresponding sense of purpose to care about others as much as, if not more than, oneself. A core principle of leading a meaningful life is to make it more than just about yourself.

2. Meaningful work and career. Having a passion for work and a long-term career gives most people a drive to achieve goals beyond the needs of themselves and their immediate family that lifts all of us to a higher plane, and society toward greater prosperity and moral progress. Having a reason to get up and around in the morning, and having a place to go where one is needed, is a lasting purposeful goal.

3. Social and community involvement. We are not isolated individuals but social beings with a drive to participate in the process of determining how best we should live together, for the benefit of ourselves, our families, our communities, and our societies. This is not just voting but, for example, being actively engaged in the political process; it is not just a matter of joining a club or society, but caring about its goals and the actions of the other members working toward the same goals. Get out and participate!

4. Challenges and goals. Most of us need tests and trials and things at which to aim, both ordinary, such as the physical challenge of sports and recreation and the mental challenge of games and intellectual pursuits, as well as extraordinary, such as striving for abstract principles like truth, justice, and freedom, and struggling through obstacles in the way of realizing them.

5. Transcendency and spirituality. Possibly unique to our species is the capacity for aesthetic appreciation, spiritual reflection, and transcendent contemplation through a variety of expressions such as art, music, dance, exercise, sports, meditation, prayer, quiet contemplation, religious revere, and spiritual contemplation, connecting us to that which is outside of ourselves, and generating a sense of awe and wonder at the vastness of humanity, nature, the world, and the cosmos. The idea that we live in a universe that is 13.8 billion years old, and on a planet that is but one among trillions of planets in our galaxy alone, itself one of hundreds of billions of other galaxies, in a universe that is possibly just one in a multiverse of universes, is so staggering a thought as to leave one speechless in reverence for the vastness of it all.

I will end this reverie on lessons for life with an inspiring poem that completely changed how I looked at my life when I first encountered it. It’s called Invictus, written in 1920 by William Ernest Henley, and is particularly poignant as he wrote it when he was terminally ill:

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

Please consider supporting Skeptic by becoming a free or paid subscriber below. All monies go to the Skeptics Society, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit educational organization.

Upgrade to paid

###

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.

Science of Genesis Paradise Lost – Part 8 Dating Problems (feat. Genetically Modified Skeptic)

Anaïs Nin on the Meaning of Life and the Dangers of the Internet, Before the Internet

Here’s the link to this article.

“We believe we are in touch with a greater amount of people… This is the illusion which might cheat us of being in touch deeply with the one breathing next to us.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

Last week’s widely reverberating meditations on the meaning of life by cultural icons like Charles Bukowski, Annie Dillard, Arthur C. Clarke, and John Cage reminded me of a passage from the altogether sublime The Diary of Anais Nin, Vol. 4: 1944-1947 (public library) — the same tome that gave us this poignant reflection on why emotional excess is essential to creativity.

In an entry from May 1946, Anaïs Nin once again challenges our presentism bias by thinking deeply and timelessly about issues we tend to believe we’re brushing up against for the very first time, from the pitfalls of always-on communication technology to the pace of modern life to the venom of procrastination.

Even more interesting than the striking similarity between what Nin admonishes against and the present dynamics of the internet is the fact that she essentially describes Marshall McLuhan’s seminal concept of the global village… a decade and a half before he coined it. She writes:

The secret of a full life is to live and relate to others as if they might not be there tomorrow, as if you might not be there tomorrow. It eliminates the vice of procrastination, the sin of postponement, failed communications, failed communions. This thought has made me more and more attentive to all encounters, meetings, introductions, which might contain the seed of depth that might be carelessly overlooked. This feeling has become a rarity, and rarer every day now that we have reached a hastier and more superficial rhythm, now that we believe we are in touch with a greater amount of people, more people, more countries. This is the illusion which might cheat us of being in touch deeply with the one breathing next to us. The dangerous time when mechanical voices, radios, telephones, take the place of human intimacies, and the concept of being in touch with millions brings a greater and greater poverty in intimacy and human vision.

For more on Nin’s timeless insights on life, see Lisa Congdon’s stunning hand-lettered diary quotes.