I’m currently taking a writing and blogging sabbatical due to family health issues. For now, I’ll repost selected articles from my Fiction Writing School.

Here is the link to this article.

by Lewis Jorstad / March 22, 2022 / Character Development

The word “hero” carries a lot of weight.

Classic heroes are a staple of nearly all fiction, regardless of the genre you’re writing in. These characters are those who face seemingly impossible challenges, rise to the occasion, and then return to share the rewards of their journey with their community.

At first glance, this “hero’s journey” seems universal, and in many ways it is. However, there’s another side to this story that doesn’t match up with the traditional hero—and that is the heroine. Believe it or not, heroes and heroines aren’t the same. So, in this article, let’s explore all the differences between the hero and heroine, along with why these character types have nothing to do with gender!

Who Are the Hero and the Heroine?

Contents [hide]

A few years back, I wrote a post focused on the twelve stages of the hero’s character arc.

In that article, I explained that this arc is based on Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, which states that all fictional heroes follow the same common patterns—which Campbell calls the “monomyth.” In this theory, the hero’s quest is about a character leaving home, facing a series of tests and trials, and then using the lessons they learned to heal and preserve their community for the future.

It’s this “return” that sets the hero apart from the rest of your cast.

By making the difficult choice to return home, your hero caps off what is basically a three-part journey:

The Known World:

The hero begins in their normal world. This represents stability and the status quo, though there are undeniable flaws beginning to form. Most heroes are discontent in their known world, even if they appreciate the security it provides.

Facing the Unknown:

This shifts when the hero enters the unknown, a wild place filled with possibility. This is where they’ll face tests and trials that help them attain mastery of their new world, eventually equipping them with the tools they need to resolve their story’s conflict.

Returning to the Known:

Finally, the hero returns to the known. By now, they fully understand their community’s flaws, and use that understanding to heal their world. In the process, they become a hero, safeguarding their community and ensuring its future for years to come.

This journey is what forms the foundation of the “hero’s character arc,” which takes these more plot-focused elements and translates them into a character-centric framework. Of course, these are just the basics! There are a whole variety of unique story beats that characterize a well-written hero, along with their cyclical journey from known to unknown.

This is where the heroine comes into play.

You see, the hero and the heroine’s arc both follow this three-part structure. What sets them apart, however, is their focus. While the hero’s character arc is all about a character gaining physical mastery over their world, the heroine’s arc is much more concerned with their mastery over their own mind.

In the end, this has nothing to do with gender, and there are plenty of excellent female heroes and male heroines out there. Instead, these two character arcs act as mirror images—with one focused on an external quest, and the other on an internal one.

The Hero’s Arc vs. The Heroine’s Arc

The Hero’s Arc – External:

So, how do these arcs compare?

Well, we’ll start by discussing the hero’s arc. This is what most people associate with the classic hero, so it provides a great baseline for understanding how these character arcs unfold:

The Known World:

The hero begins their story suffering from some inner struggle. Meanwhile, their community is suffering too. Though they might not realize it just yet, a powerful threat is brewing beneath the surface—both within and outside of their known world.

A Threat Revealed:

This threat reveals itself at the Catalyst, forcing the hero to leave their known world behind in search of some reward. This is where they first step foot into the unknown.

Entering the Unknown:

Once in the unknown, the hero will face a variety of challenges, learning and adapting as they struggle to get their bearings. Along the way, they’ll start to understand the flaws of their community, though they won’t know how to handle those flaws just yet.

Receiving Their Reward:

This culminates in a major test, where the hero embraces their truth and receives their reward. This could be anything from a new skill to key allies, powers, or physical tools. Whatever it is, it’s rarely what the hero expected at the start of their quest.

Dreading the Return:

Now comfortable in the unknown world, the hero will dread returning home. They’ve attained mastery over the unknown, and are hesitant to leave. Instead, they make plans to resolve their story’s conflict without abandoning the unknown world.

Facing Failure:

Unfortunately, this falls through. After a major defeat, the hero is forced to question their place in the unknown, as well as the fate of their known world. If either is to survive, they must sacrifice their own desires in order to protect them.

Becoming a Hero:

Realizing their reward is the secret to saving their community, the hero makes the choice to leave the unknown world and return home. In a final test, they share their reward and sacrifice a part of themselves for the greater good, earning the title of hero.

Finally at Peace:

With their community safe, the hero is left with a foot in both worlds. No longer restricted to one or the other, they bridge the gap between the known and unknown.

As you can see, this hero’s arc is tightly focused on the hero’s physical mastery over their world—though it still contains all the elements of a successful character arc. Though they’ll still have to confront their inner struggle and (eventually) embrace their truth, the main reward they gain is external.

For instances, consider Disney’s Mulan.

Mulan begins her story when she sets out to protect her father from the draft, only to find herself struggling to survive in the Chinese army. Luckily, she eventually gains mastery over this new unknown world, until she eventually defeats the warlord threatening her people. In doing so, she returns home with honor, rising to the status of hero and completing her hero’s character arc.

This is a great example of the hero in action. Though Mulan learns a lot about herself and overcomes her inner struggle throughout her journey, her story is primarily about overcoming physical threats—and thus attaining physical mastery.

The Heroine’s Arc – Internal:

In contrast, the heroine takes a different approach.

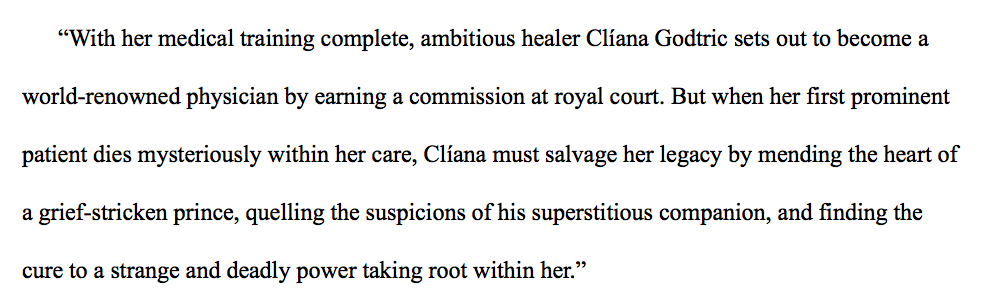

This character starts out in the same known world, suffering from a similar inner struggle—but, rather than set out on a physical quest, they leave home in search of their true self. This journey is all about wisdom, identity, and internal connections, following the heroine as they slowly rekindle their connection to who they really are:

The Known World:

The heroine begins their story suffering from some inner struggle, taking shape as an internal disconnect. Meanwhile, their community is suffering too. Though they might not realize it yet, a powerful threat is brewing beneath the surface—both within and outside of their known world.

A Threat Revealed:

This threat reveals itself at the Catalyst, forcing the heroine to leave their known world and enter the unknown in search of the wisdom needed to protect their people.

Entering the Unknown:

Once in the unknown world, the heroine will face a variety of challenges, learning and adapting as they struggle to shed the weight of their old identities. Along the way, they’ll begin to understand the flaws of their community, though they won’t know how to handle those flaws just yet.

Discovering Themselves:

This culminates in a major test, where the heroine embraces their truth and rekindles their connection with their true self. This internal change is typically represented by some symbolic action.

Then and Now:

Now comfortable in the unknown world, the heroine will dread returning home, unsure how to reconcile their old self with their new identity. Instead, they make plans to resolve their story’s conflict without abandoning the unknown.

Facing Failure:

Unfortunately, this falls through. After a major defeat, the heroine is forced to question their new identity, as well as the fate of their known world. If their community is to survive, they must accept who they are without fear.

Sharing Their Wisdom:

Realizing this wisdom is the secret to saving their community, the heroine makes the choice to leave the unknown and return home. In a final test, they share their true self and sacrifice a part of themselves for the greater good, earning the title of heroine.

Finally at Peace:

With their community safe, the heroine is left with a foot in both worlds. No longer restricted to one or the other, they bridge the gap between the known and unknown, finally at peace with who they are.

Right away, you can hopefully see how this heroine’s arc mirrors the hero’s arc—just with a more internal focus. While the heroine will still face plenty of physical conflicts, their true reward is the wisdom to heal both themselves and their community.

A great example of this is Moana.

Much like Mulan, Moana sets out into the unknown in order to protect her family. However, her story isn’t about physical mastery. Though she absolutely faces physical trials throughout her journey, her ultimate triumph is instead discovering her ancestry and accepting her emotional bond with the ocean. It’s this deeper understanding of herself that eventually allows her to save her people, thus marking her as a heroine.

A Note on Primary vs. Secondary Arcs

With those differences in mind, what should you do with all of this information?

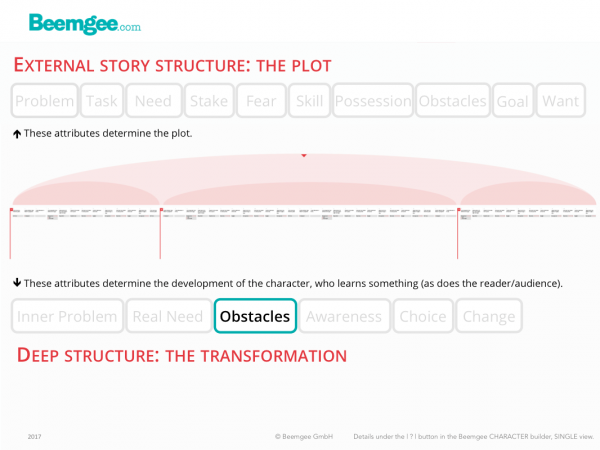

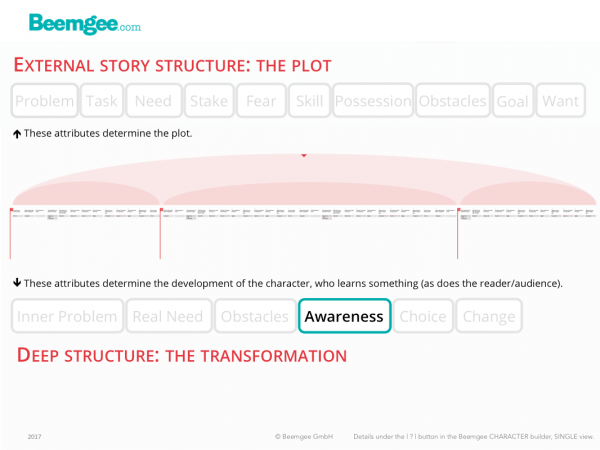

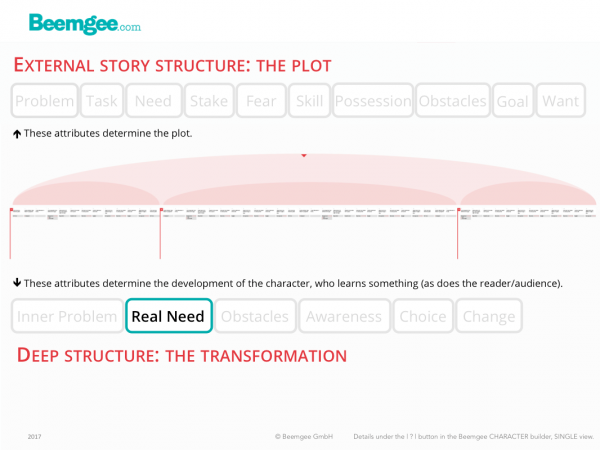

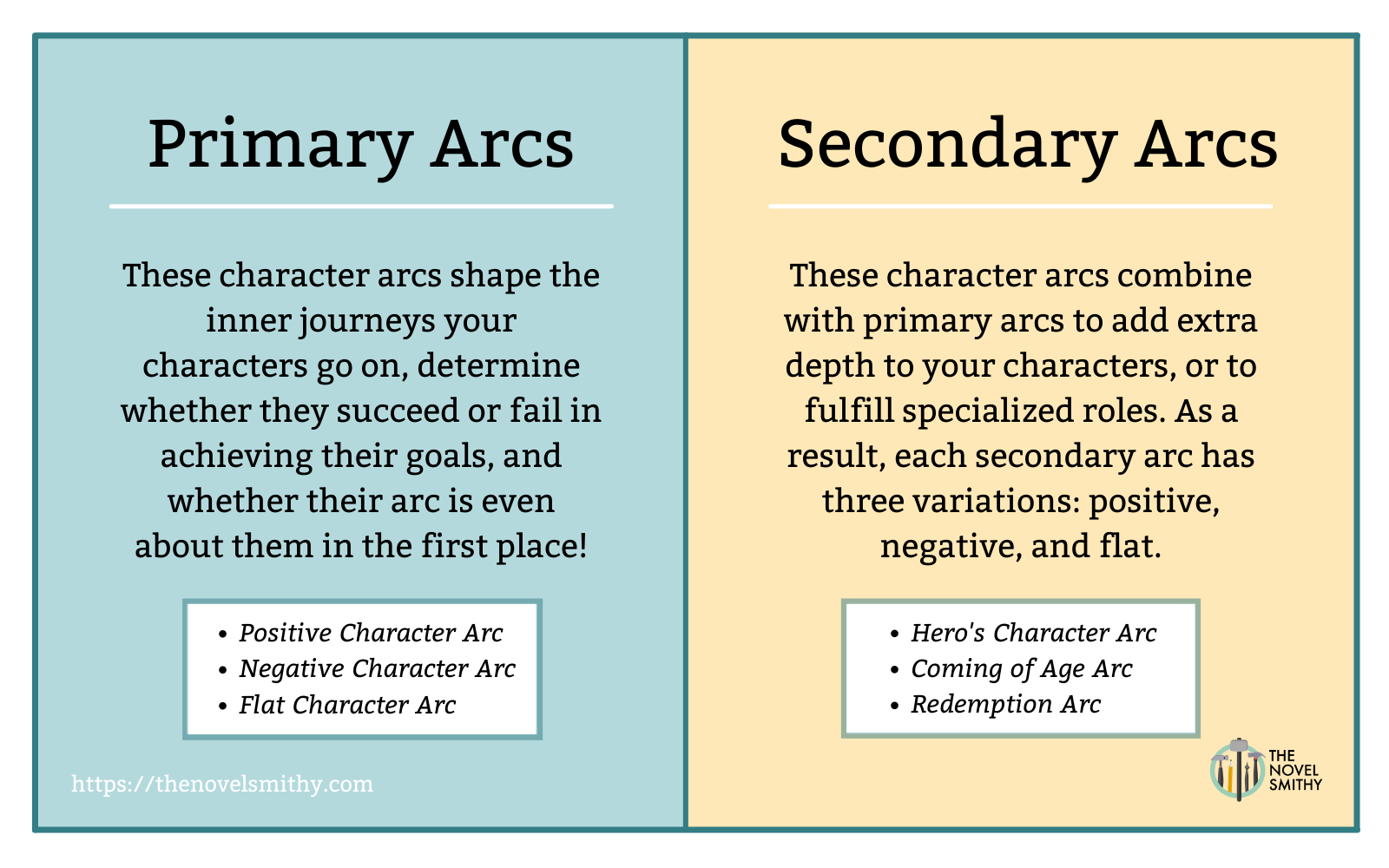

Well, the first thing you’ll want to consider is that the hero and heroine’s arcs are secondary arcs. This is a term I’ve mentioned in past articles, but it essentially describes a subset of character arcs. Secondary arcs are optional, specialized patterns you can use to create specific types of characters like the elder, rogue, or hermit—along with the hero and heroine.

Meanwhile, primary arcs are the type of character arc most writers are familiar with. These are your classic positive, negative, and flat arcs, which determine the overarching journey your character goes on, whether they achieve their goals, and how their story concludes.

What makes this distinction important is that secondary arcs layer on top of primary arcs—meaning that, if you want to use a secondary arc to craft your hero, you’ll first need to consider their overall journey.

NOTE: If you’d like to explore other primary and secondary character arcs, these articles are a great place to start:

Writing the Hero vs the Heroine

Ultimately, the terms “hero” and “heroine” are tangled up in all kinds of preconceived ideas, and those ideas can make it hard to see our characters for who they really are. Personally, this is why I find these character arcs so valuable! By understanding the specific journey each of these types of heroes goes on, I can look at my cast objectively and build better, more engaging stories.

The key is simply one of focus.

While the hero’s story is all about their journey into the unknown in search of physical mastery, the heroine’s is all about their quest to better understand their own mind. Because of this, the hero’s arc is mostly an external one, while the heroine’s arc is primarily internal.

Lewis Jorstad is an author and editor, a lover of reading and travel, and the steward of a very creaky sailboat. He hopes to visit every country in the world before he dies, but for now he spends his time teaching up-and-coming writers the skills they need to write their dream novels. Interested? Read more here or get in touch.