Here’s the link to this article.

Why Oliver Cromwell was right to beseech you to think it possible you may be mistaken

Very much not in the spirit of “just asking questions,” which is so pervasive among creationists, climate deniers, anti-vaxxers, 9/11 Truthers, Obama Birthers, QAnoners and many others that it has its own skeptical descriptor—JAQing off—I present here some challenging questions for Christians and other religious believers.

I realize that faith doesn’t always open itself to rational inquiry and empirical testing, otherwise it wouldn’t be faith, or “the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things unseen” (Hebrews 11:1). But in this age of science and rationality—the twin pillars of Enlightenment humanism—a great many Christians and members of other faiths contend that their claims are true, not in the mythic or metaphorical sense, but in the literal sense.

Skeptic is a reader-supported publication. All monies go to the Skeptics Society, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Upgrade to paid

There really is a God called Yahweh. God really created the universe and everything in it. God really vouchsafed to us humans consciousness, morality, and meaning. God really performs miracles. God really grants everlasting life after the provisional proscenium of this world. And so forth.

For over four decades—after my own seven-year stint as an evangelical Christian—I have engaged believers in countless conversations and dozens of formal debates, so I can assure readers that for a great many religious people their beliefs are literally true, in the Enlightenment sense of knowledge as justified true belief. That is, they believe that there are arguments and evidence for religious claims substantial enough to be considered “true,” which I define (in Why People Believe Weird Things) as: a claim for which the evidence is so substantial it would be reasonable to offer one’s provisional assent.

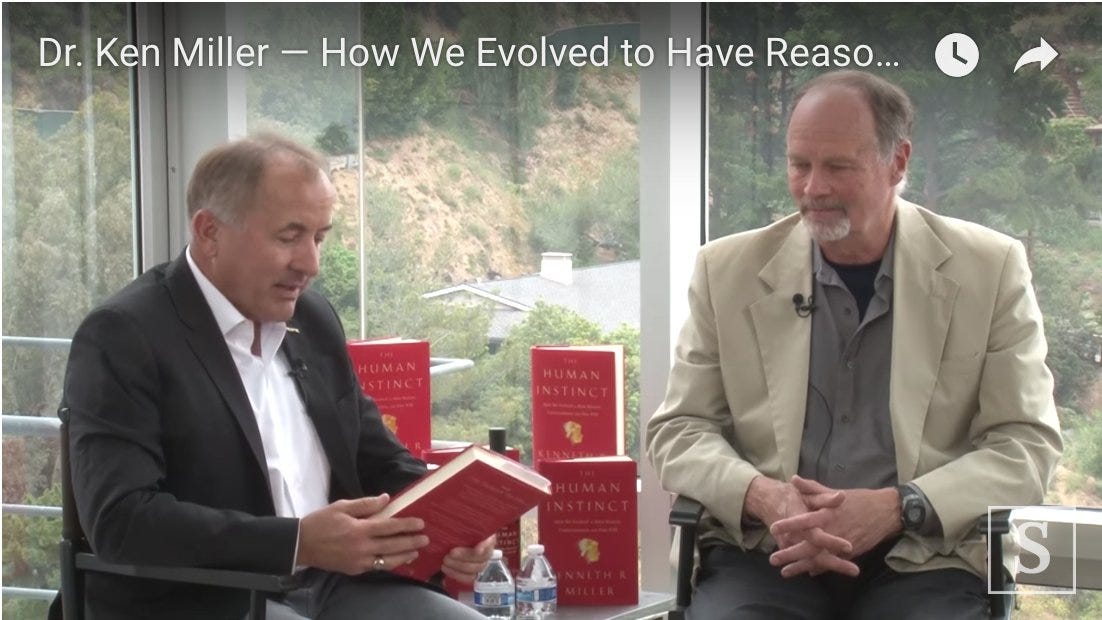

I rarely hear such sentiments as “this is my faith—I’m not claiming that it is literally true.” Or “this is just what I believe and I’m not trying to convince you that you should believe it too.” Or “this is what people of my faith believe but people in other faiths believe something different and all are equally true.” Such qualifiers are rare enough in my world that I can (and have) identified who declared them. The renowned biologist Ken Miller is one, a self-declared Catholic who nevertheless isn’t claiming the central tenets of which are scientific conclusions.

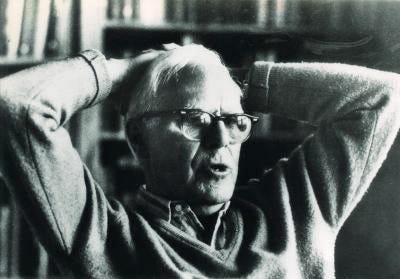

Another is Martin Gardner, one of the founders of the modern skeptical movement and a debunker of all forms of flimflam and flapdoodle, who nevertheless declared himself a philosophical theist, or sometimes a fideist—someone “who believes something on the basis of emotional reasons rather than intellectual reasons,” as he told me in an interview:

People think that if you don’t believe Uri Geller can bend spoons then you must be an atheist. But I think these are two different things. I call myself a philosophical theist in the tradition of Kant, Charles Peirce, William James, and especially Miguel Unamuno, one of my favorite philosophers. As a fideist I don’t think there are any arguments that prove the existence of God or the immortality of the soul. Even more than that, I agree with Unamuno that the atheists have the better arguments. So it is a case of quixotic emotional belief that is really against the evidence and against the odds. The classic essay in defense of fideism is William James’ The Will to Believe. James’ argument, in essence, is that if you have strong emotional reasons for a metaphysical belief, and it is not strongly contradicted by science or logical reasons, then you have a right to make a leap of faith if it provides sufficient satisfaction.

It makes the atheists furious when you take this position because they can no more argue with you than they can argue over whether you like the taste of beer or not. To me it is entirely an emotional thing.

I pressed Martin to expand on his comment that atheists’ arguments are better than theists’ arguments:

Well, they are better in the sense that the theist has a tremendous problem of explaining the existence of evil, and to me that is the strongest argument against God. If there is a God and he is all powerful and all good, why does he allow evil into the world? Evil exists, so is God all good but not all powerful? Or is he all powerful but not all good? That is a very powerful argument and I don’t know of any good way to answer it.

What about the afterlife, I inquire?

If you believe in God at all, I think you have to believe in a personal God, in a sense. That is, you have to assign to God something analogous to human mind because that is the highest type mind we are acquainted with. If God is just another name for nature then I think it is more honest just to say we are humanists.

Indeed, this is why I call myself a humanist, or more specifically an Enlightenment humanist, but this is not what most people believe by “God”, which Gardner acknowledged:

No, and of course if you do believe in a personal God it is in an analogical sense, so I sometimes like to call myself a theological positivist because I agree completely with Carnap that metaphysical questions are meaningless—if you can’t get at it by logic or by science you really can’t say anything at all about the question.

If you ask me for details about the nature of God I would have to answer “I don’t know.” The kind of God I believe in is so completely transcendent and so wholly Other that you really can’t say anything about God’s nature. To ask, for example, whether God is inside or outside of time, I have no idea what this means or how to reply to it. I can understand arguments saying he is in time, coming from the process theologians; on the other hand I can understand the arguments that place God completely outside of time, in some sort of realm in which time has no meaning. But these are metaphysical arguments and Carnap would say they are meaningless questions, and I would agree to that.

If this is what you believe, that is, you are a philosophical theist in this pragmatic fideist tradition, then the following questions are not for you. If you are a religious believer in the more traditional sense, or if you know people who are, then these questions may prove challenging. (In appreciation and acknowledgment of my friend and colleague Michael Aisner for the inspiration for this exercise.) If you would like to provide answers to or comment on any of these questions feel free to use the Comments section below.

* * *

Given that there dozens of major religions, hundreds of minor religions, and thousands of religious sects, that they often differ substantially in their core beliefs does this suggest one of them is the “right religion” and all the rest are “wrong” (in some epistemological sense), or could it be that they are all human constructions and none of them are right (in an ontological sense)?

If you were raised in a different religion, do you think you would now belong to that religion instead and believe it as much as you do your current religion?

If you pray and hear the voice of God in your head, how can you tell that it is God talking to you or just the normal voices in the head that we all experience?

If that voice of God commanded you to do something immoral or illegal, would you do it? That is, if the voices in your head are a form of evidence for God’s providence, how do you decide which commandments to follow and which to reject?

The bible and other holy books are chockablock full of moral prescriptions (what we should do) and proscriptions (what we shouldn’t do), but they often contradict one other (do I love my neighbor as myself or should I smite them as moral enemies) or are in conflict with modern morals and laws (slavery, torture, capital punishment), so how do you decide which ones to obey and which to ignore?

Echoing Plato’s “Euthyphro’s dilemma” (“whether the pious or holy is beloved by the gods because it is holy, or holy because it is beloved of the gods?”), does God embrace moral principles naturally occurring and external to Him because they are sound (“holy”) or are these moral principles sound only because God says that they are sound or otherwise they wouldn’t be? If moral principles hold value only because we believe that God created them, then what is their value if there is no God? Do we really need God to tell us that murder, rape, slavery, torture, pedophilia, lying, and stealing are wrong?

If God is omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent, and thus he knows what is in your heart and mind, why does he require you to demonstrate your faith by worshiping him? In any case, why would such a being need to be worshipped? Isn’t worshipfulness a human desire often affiliated with dictators, demagogues, and authoritarians of all stripes?

If God is omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent, why do holy books describe him as surprised or angered by the actions of humans? Shouldn’t he have known what was going to happen?

If God is omniscient, omnipotent, and omnibenevolent, then how can Jesus be his son and God at the same time? Doesn’t this violate Aristotle’s Law of Identity, or A is A, or “everything is the same as itself and different from another” (Metaphysics IV, 3)?

If God is Jesus is vice versa, then the Christian claim that one must accept Jesus as one’s savior from original sin in order to have everlasting life (and not spend an eternity in hell), doesn’t this mean that God sacrificed…himself…to himself…to save us from himself?

When did Jesus become a capitalist? Didn’t he caution his followers about the dangers of wealth and the worship of money, didn’t he admonish the money changers, and didn’t he preach that it would be easier “for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God” (Matthew 19:23)?

If missionaries from your religion are sent to evangelize and convert people in other countries, should missionaries from other religions be sent to your country for the same reason?

When you declare a miracle, does this mean you understand everything that is possible in nature? Could it be that the said miracle is just something that happened for which you have no explanation (the argument from ignorance, or the God of the Gaps argument)?

If God answers prayers and sometimes they seem to come true—say, the healing of someone’s cancer, recovery from a horrific accident, or survival in a seemingly deadly situation—what about all the devout believers who (and whose devout families) fervently prayed for them and they nevertheless died or suffered unmercifully?

If God can heal cancers, cure deadly diseases, enable pregnancies, and perform countless signs and miracles, why can’t he grow new limbs on Christian soldiers maimed in battle? Salamanders can grow new limbs, so why can’t God do that for his faithful and worshipful followers?

Can a mass murderer, serial killer, or child abuser go to heaven if, just before death, he accepts Jesus as his savior? Wouldn’t it be more just if he burned in hell for eternity for his deeds? In other words, don’t works matter more than words?

Do the mass murdering and torturing Crusaders and Inquisitors make it into the Christian heaven if they accepted Jesus as their savior?

If aliens exist on other worlds and they have never heard of your God, what happens to them? Does Jesus visit all exo-planets that contain sentient beings? Are there the equivalent of alien Romans who torture and murder Jesus, who rises from the dead to atone for their original alien sins?

* * *

I have many more such questions, but that should suffice for now to (hopefully) at least give Christians and other religious believers pause in their confidence in the verisimilitude of their knowledge assertions. Perhaps—and here hope springs eternal—religious believers might consider the skeptical admonitions of Oliver Cromwell in his letter to the general assembly of the Church of Scotland on August 3, 1650:

Is it therefore infallibly agreeable to the Word of God, all that you say? I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken.

Skeptic is a reader-supported publication. All monies go to the Skeptics Society, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Upgrade to paid

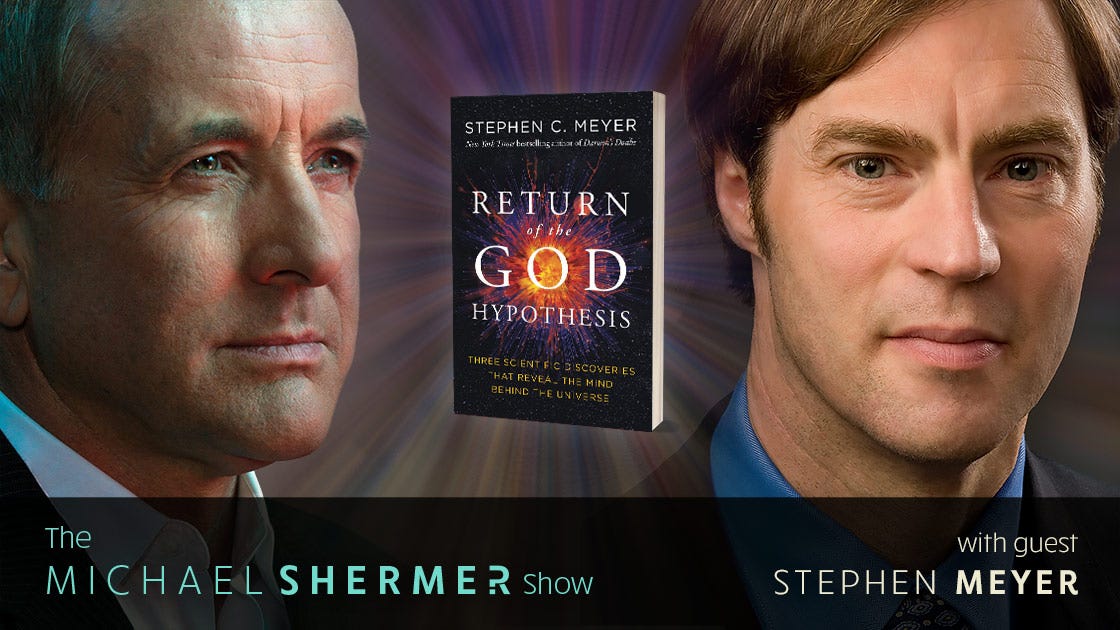

Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, the host of The Michael Shermer Show, and a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University. His many books include Why People Believe Weird Things, The Science of Good and Evil, The Believing Brain, The Moral Arc, and Heavens on Earth. His new book is Conspiracy: Why the Rational Believe the Irrational.