Here’s the link to this article.

“If equal affection cannot be, let the more loving one be me.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

This is the seventh of nine installments in the animated interlude season of The Universe in Verse in collaboration with On Being, celebrating the wonder of reality through stories of science winged with poetry. See the previous installments here.

THE ANIMATED UNIVERSE IN VERSE: CHAPTER SEVEN

In 1865 — a year before the German marine biologist Ernst Haeckel coined the word ecology, the year Emily Dickinson composed her stunning pre-ecological poem about how life-forms come into being — the German physicist Rudolf Clausius coined the word entropy to describe the undoing of being. The thermodynamic collapse of physical systems into increasing levels of disorder and uncertainty. The dissolution of cohesion along the arrow of time. Inescapable. Irreversible. Perpetually inclining us toward, in poet Mary Ruefle’s perfect phrase, “the end of time, which is also the end of poetry (and wheat and evil and insects and love).” Perpetually ensuring, in poet Edna St. Vincent Millay’s perfect phrase, that “lovers and thinkers” become “one with the dull, the indiscriminate dust.”

This transformation of order into disorder, of constancy into discontinuity, is how we register change and tell one moment from the next. Without entropy, the universe would be a vast eternal stillness — a frozen fixity in which never and forever are one. Without entropy, there would be no time — at least not for us, creatures of time.

Clausius built on the Greek word for transformation, tropē, because he believed that leaning on ancient languages to name new scientific concepts made them available to all living tongues, belonging to all people for all time. It pleased him, too, that entropy looked like energy — its twin in the making and unmaking of the universe. Energy, the giver of life. Entropy, the taker away. The frayer of every cell that animates our bodies with being. The extinguisher of every star that unlooses its thermal energy into the cold sublime of spacetime as it runs out of fuel, warming up the orbiting planets with its dying breath. We are only alive because our Sun is burning out. Without entropy, there would be no us.

The child of a physicist, W.H. Auden (February 21, 1907–September 29, 1973) had no illusion about the entropic nature of reality — a science-lensed lucidity he wove into his poetic search for truth, for meaning, for a way to live with our human fragility, with our twin capacities for terror and tenderness inside an impartial universe he knew to be impervious to our plans and pleas. The child of two world wars, he had no illusion about how our humanity comes unwoven by its own pull but is also the enchanted loom that makes life worth living.

Just as Auden was reaching the peak of his poetic powers, the world’s deadliest war broke out, brutal and incomprehensible. It may be that art is simply what we call our most constructive coping mechanism for the incomprehension of life and mortality, and so Auden coped through his art. He looked at the stars and saw “ironic points of light” above a world “defenseless under the night”; he looked at himself and saw a creature “composed like them of Eros and of dust, beleaguered by the same negation and despair.”

“September 1, 1939” became a generation’s life-raft for “the waves of anger and fear” subsuming the unexamined certainties of yore, splashing awake the “euphoric dream” of a final and permanent triumph over evil. But the war went on, and in the protracted post-traumatic reckoning with its aftermath — this gasping ellipsis in the narrative of humanity — Auden revised his understanding of the world, of life, of our human imperative, and so he revised his poem.

In what may be the single most poignant one-word alteration in the history of our species, he changed the final line of the penultimate stanza to reflect his war-annealed recognition that entropy dominates all. The original version read: “We must love one another or die” — an impassioned plea for compassion as a moral imperative, the withholding of which assures the destruction of life. But the plea had gone unanswered and eighty million lives had gone unsaved. Auden came to feel that his reach for poetic truth had been rendered “a damned lie,” later lamenting that however our ideals and idealisms may play out, “we must die anyway.”

A decade of disquiet after the end of the war, he changed the line to read: “We must love one another and die.”Liminal Days. (Available as a print.)

But there was a private reckoning beneath the public one — this, after all, is the history of humanity, of our science and our art. Auden was working out the world in the arena where we so often wrestle with the vastest, austerest, most abstract and universal questions about how reality works — the fleshy, feeling concreteness of personal love.

In the summer of 1939, just before the world came unworlded, Auden met the young aspiring poet Chester Kallman and fell in love, fell hard, fell dizzily into the strangeness of spending “the eleven happiest weeks” of his life amid a world haunted by death. Over the next two years, as the war peaked, this passionate love became a lifeline of sanity and survival. But Auden, already well into his thirties, kept longing for a stable and continuous relationship of mutual fidelity — the closest thing to a marriage their epoch allowed — and Kallman, barely twenty, kept wounding him with the scattered and discontinuous affections of self-discovery.

Throughout the cycles of heartache, Auden refused to withdraw his love — a stubborn and devoted love, opposing the forces of dissolution and disorder, outlasting the fraying of passion and the abrasions of romantic disappointment, until it buoyed their bond over to the other side of the tumult, to the stable shore of lifelong friendship.

For the remainder of his life, Auden summered with Kallman in Europe. They spent twenty New York winters as roommates in a second-floor apartment at 77 St. Marks Place in the East Village, later marked with a stone plaque emblazoned with lines from Auden’s ode to the foolish, fierce devotion that had prevailed over the lazy entropy of romantic passion to salvage from its wreckage the lasting friendship, the mutual cherishment and understanding that had bound them together in the first place.

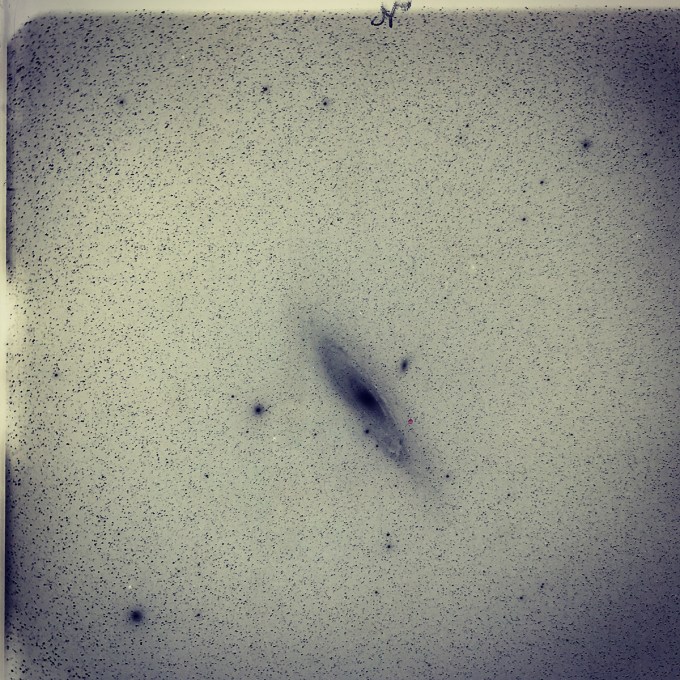

“The More Loving One” — the second verse of which became the epigraph of Figuring, and which appears in Auden’s indispensable Collected Poems (public library) — is a poem both profoundly personal and profoundly universal, radiating a reminder that no matter the heartbreak, no matter the entropic undoing of everything we love and are, we are survivors. It is at once a childish fantasy chalked on the blackboard of consciousness — we do not, after all, survive ourselves — and a blazing manifesto for being, for the measure of maturity, for the only adequate attitude with which to go on living with the incremental loss that is life itself.

In this seventh installment of the animated interlude season of The Universe in Verse (which returns as a live show next week), “The More Loving One” comes alive in a reading by astrophysicist, author, and OG Universe in Verse collaborator Janna Levin (who has previous inspirited many a splendid poem), animated by Taiwanese artist and filmmaker Liang-Hsin Huang, and winged with original music by Canadian double bassist, composer, and nature-celebrator Garth Stevenson.

THE MORE LOVING ONE

by W.H. AudenLooking up at the stars, I know quite well

That, for all they care, I can go to hell,

But on earth indifference is the least

We have to dread from man or beast.How should we like it were stars to burn

With a passion for us we could not return?

If equal affection cannot be,

Let the more loving one be me.Admirer as I think I am

Of stars that do not give a damn,

I cannot, now I see them, say

I missed one terribly all day.Were all stars to disappear or die,

I should learn to look at an empty sky

And feel its total dark sublime,

Though this might take me a little time.

Previously in the series: Chapter 1 (the evolution of life and the birth of ecology, with Joan As Police Woman and Emily Dickinson); Chapter 2 (Henrietta Leavitt, Edwin Hubble, and the human hunger to know the cosmos, with Tracy K. Smith); Chapter 3 (trailblazing astronomer Maria Mitchell and the poetry of the cosmic perspective, with David Byrne and Pattiann Rogers); Chapter 4 (dark matter and the mystery of our mortal stardust, with Patti Smith and Rebecca Elson); Chapter 5 (a singularity-ode to our primeval bond with nature and each other, starring Toshi Reagon and Marissa Davis); Chapter 6 (Emmy Noether, symmetry, and the conservation of energy, with Amanda Palmer and Edna St. Vincent Millay).