Here’s the link to this article by Joyce Carol Oates.

Five Motives for Writing

Originally published in The Kenyon Review, New Series, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Fall 2014)

Edited and arranged by Robert Friedman

It is a very self-conscious thing to speak of one’s “credo.”

I think that most writers and artists love their work, which of course we don’t consider “work”—exactly. As artists love the basic materials of their art—paints, charcoal, clay, marble—so writers love the basic materials of their art—language.

Many visual artists have no “credo” at all. They offer no “artist’s statement.” And they consider those who do to be somewhat suspicious, if not frankly duplicitous.

The oracular, pontificating, self-aggrandizing vatic voice—how hollow it sounds, to others! There are great poets, including even Walt Whitman and Robert Frost, who might have known better, who have fallen into such hollowness, as one might fall into a bog.

Recall D. H. Lawrence’s admonition—Never trust the teller, trust the tale.

Criticism, as distinct from literature, or “creative” writing, has often been aligned with a particular moral, political, religious sensibility. The 1950s were perceived, proudly and without irony, as an Age of Criticism—at least, by critics. (It does seem rather narrow to define the 1950s as an age of criticism when writers like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Eudora Welty, and Flannery O’Connor, among numerous others, were publishing frequently.) Criticism is more naturally a kind of preaching, or propaganda; there are systems of belief underlying most criticism, intent upon rewarding those who confirm the critic’s core beliefs and punishing those who don’t. But “creative” artists resist defining their beliefs so overtly, as one might wish not to wear one’s clothing inside-out revealing seams and stitches.

However, considering my own life, or rather my career, I think it is likely that my credo, if I were to have one, involves several overlapping ideals.

Subscribe

Commemoration

Much of literature is commemorative. Home, homeland, family, ancestors. Mythology, legend. That “certain slant of light” in a place deeply imprinted in childhood, as in the oldest, most prevailing region of the brain.

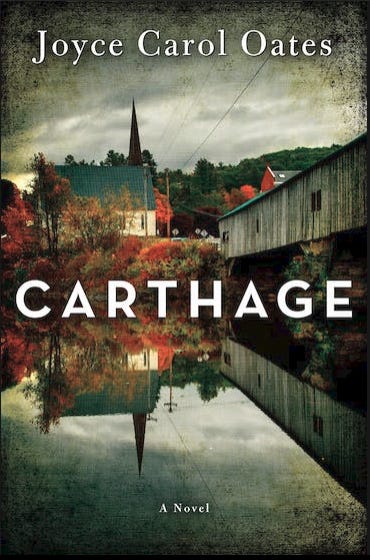

Much of my prose fiction is “commemorative” in essence—it is a means of memorializing a region of the world in which I have lived, a past I’ve shared with others, a way of life that might seem to me vanishing, thus in danger of being forgotten. Not an “old” America but rather an “older” America—those years described as the Depression, through World War II, the Vietnam War, the 1960s, and so forward to the present time in upstate, quasi-rural America. Writing is our way of assuaging homesickness.

Commemoration is identical, for me, with setting. Where a story or a novel is set is at least as significant as what the story—the plot—“is.” In my fiction, characters are not autonomous but arise out of the very physicality of the places in which they live and the times in which they live. There is a spiritual dimension to landscape that gifted photographers can suggest and gifted writers can evoke.

Often, I am mesmerized by the descriptions of landscapes, towns, and cities in fiction—(obviously, the novels of Dickens, Hardy, Lawrence come to mind; it is difficult to name any novels of distinction that are not firmly imbued with “place.”) And if the setting is antagonistic to the spirit, as in our environmentally devastated landscapes and cityscapes, this is a part of the story.

Bearing witness

Most of the world’s population, through history, have not been able to “bear witness” for themselves. They lack the language, as well as the confidence, to shape the language for their own ends. They lack the education, as well as the power that comes with education. Politically, they may be totally disenfranchised—simply too poor, and devastated by poverty and the bad luck that comes with poverty, like an infected limb turning gangrenous. They may be suppressed, or terrorized into silence. My most intense sympathies tend to be for those individuals who have been left behind by history, as by the economy; they are all around us, but become visible only when something goes terribly wrong, like a natural disaster, or an outburst of madness and violence.

Particularly, I have been sympathetic with the plight of women and girls in a patriarchal society; I am struck by the ways in which weakness can be transformed into strength and vulnerability into survival.

If the writer has any obligation—and this is a debatable issue, for the writer must remain free—it’s to give voice to those who lack voices of their own.

Self-expression

The “self” is, at its core, radically young, even adolescent. Our “selves” are forged in childhood, burnished and confirmed in adolescence. That is why there are great, irresistibly engaging writers of “adolescence”—for instance, Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Ernest Hemingway (in his early short stories set in northern Michigan).

Since I began writing fairly seriously when I was very young, my truest and most prevailing self is that adolescent self, confronting an essentially mysterious and fascinating adult world, like a riddle to be solved, or a code to be decoded. The essence of the adolescent is rebelliousness, skepticism. It is very healthy, a stay against the accommodations and compromises of what we call adulthood, particularly “middle age.”

Propaganda, “moralizing”

Once, it was not considered gauche for literary writers (Stowe, Upton Sinclair, Tolstoy, Eliot, Dickens) to address the reader more or less directly, and to speak of moral predilections; now, since the revolution in sensibility generally associated with the early decades of the twentieth century, which we call Modernism, it is virtually impossible to indicate a moral position in any dogmatic way. Ours is still, over all, an age of irony—indirection, obliquity. As Emily Dickinson advises, speaking of her own credo—“Tell all the truth but tell it slant / Success in circuit lies.” And Virginia Woolf, in these thrilling, liberating words:

Art is being rid of all preaching: things in themselves: the sentence in itself beautiful. . . Why all this criticism of other people? Why not some system that includes the good? What a discovery that would be—a system that did not shut out.

—Virginia Woolf

Still, most of us who write hope to evoke sympathy for our characters, as George Eliot and D. H. Lawrence prescribed; we would hope not to be reducible to a political position, still less a political party—though writers in other parts of the world are often adamantly political and are political activists—but we write with the expectation that our work will illuminate areas of the world that may be radically different from our readers’ experiences, and that this is a good thing. It is an “educational” instinct—one hopes it is not “preacherly.”

Aesthetic object

Writing as purely gestural, as Woolf suggests—“the sentence in itself beautiful.” In fact, it is very difficult to write a sustained work of fiction that is “purely gestural”— meaning emerges even out of the random, a moral perspective evolves even out of anarchy, nihilism, and amorality; the mere act of writing, still more the discipline of revision, seems to carry with it an ethical commitment to its subject. Yet most of us are drawn to art, not because of its moral gravity, but rather because it is “art”—that is, “artificial”—in some sort of heightened and rarified and very special relationship to reality, which (mere) reality itself can’t provide.

Of course, “beauty” in art can be virtually anything, including even conventional ugliness, beautifully/originally treated. In choosing a suitable language for a work of prose fiction, as well as poetry, the writer is making an aesthetic choice: she is rejecting all other languages, or “voices”; she is gambling that this particular voice is the very best voice for this material. The truism “Art for art’s sake” really means “Art for beauty’s sake”—the content of any literary novel is of less significance than the language in which the novel is told.

Now that much of publishing is digital, the book as aesthetic object is endangered. Storytelling isn’t likely to vanish, but physical, three-dimensional books comprised of actual pages (paper of varying quality) —with their “hard” covers and “dust” jackets—are in a perilous state. Many of us who love to write also love books—the phenomenon of books.

We may have been initially drawn to writing because we fell in love with a very few, select books in childhood, which we have hoped to replicate somehow; we hoped, however fantastically, to join the select society of those individuals whose names are printed on the spines of books. It isn’t to grasp at a kind of immortality—we fell into our yearning as children, long before immortality, or even mortality, was an issue. Rather, we yearn to ally ourselves with a kind of beauty, an object to be held in the hand, passed from hand to hand—an object to place upon a shelf, or to be stood upright, its beautiful cover turned outward to the world.

As Freud said memorably in Civilization and Its Discontents, “Beauty has no obvious use; nor is there any clear cultural necessity for it. Yet civilization could not do without it.”

Would the great writers of our tradition, James Joyce, for instance, have labored quite so hard, and with such fierce devotion, if the end-product of their labor was to have been nothing more than “online” art—sustained purely by electricity, bodiless, near-anonymous, instantaneously summoned as a genie out of a bottle, and just as instantaneously banished to the netherworld of cyberspace?

Like Joyce, most writers still crave the quasi-permanence of the book: not the book as idea but as physical, aesthetic object. This is as close as we are likely to come to the sacramental, which, for some of us, is wonderfully close enough.