September 8, 2022

Here is the link to this article.

For several months now I have been posting Guest Posts that were generoulsly provided by others in honor of the blog’s tenth anniversary. These posts have been wide-ranging in their content and the intriguing , each pbased on the posters’ unique backgrounds and expertise. This now is the final one in the series, the second of two posts by Michael Shermer, to continue what he was saying in his post of Sept. 3.

This one is particularly significant. Why is it in conservative Christians’ (and everyone else’s) own best interest to accept evolution as a reality of the past? He makes some compelling points. Read and see!

*************************

To counter the doubts I mentioned in my previous post, I argue that, in fact, Christians and conservatives should accept the theory of evolution for at least eight reasons (again, for brevity, truncated here):

- Evolution happened.

The theory describing how evolution happened is one of the most well-founded in all of science. Christians and conservatives embrace the value of truth-seeking as much as non-Christians and liberals do, so evolution should be accepted by everyone because it is true. In this sense, evolution is no different than any other scientific theory already fully accepted by both Christians and conservatives, such as Big Bang cosmology, heliocentrism, gravity, continental drift and plate tectonics, the germ theory of disease, the genetic basis of heredity, the aerodynamics of flight, and more.

- Evolution makes for good theology.

Christians believe in a God who is omniscient, omnipotent, and eternal. Compared to eternity, what difference does it make when God created the universe—10,000 years ago or 10,000,000,000 years ago? The glory of the creation commands reverence regardless of how many zeroes there are in the age. And compared to omniscience and omnipotence, what difference does it make how God created life—spoken word or natural forces? The grandeur of life’s complexity elicits awe regardless of what creative processes were employed. Christians should embrace evolutionary theory (and cosmology) for what it has done to reveal the magnificence of the divinity in a depth and detail unmatched by ancient texts. Darwin himself made this argument in response to his critics in the 2nd edition of On the Origin of Species:

I see no good reason why the views given in this volume should shock the religious feeling of any one. It is satisfactory, as showing how transient such impressions are, to remember that the greatest discovery ever made by man, namely, the law of the attraction of gravity, was also attacked by Leibnitz, ‘as subversive of natural, and inferentially of revealed, religion.’ A celebrated author and divine has written to me that ‘he has gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of the Deity to believe that He created a few original forms, capable of self-development into other and needful forms, as to believe that He required a fresh act of creation to supply the voids caused by the actions of His laws.

Surely God has more important things to do than to track the fall of every sparrow (Matthew 10:29).

- Intelligent Design makes for bad theology.

ID creationism reduces God to an artificer, a divine watchmaker piecing together life out of available parts in a cosmic warehouse. If God is a being in space and time, it means that He is restrained by the laws of nature and the contingencies of chance, just like all other being of this world. An omniscient and omnipotent God must be above such constraints and not subject to law and chance. God as creator of heaven and earth and all things visible and invisible would need necessarily to be outside such created objects. If He is not, then God is like us, only smarter and more powerful; but not omniscient and omnipotent. Calling God a watchmaker is delimiting.

- Evolution explains Christian family values and social harmony.

The following characteristics are shared by humans and other social mammals: attachment and bonding, cooperation and mutual aid, sympathy and empathy, direct and indirect reciprocity, altruism and reciprocal altruism, conflict resolution and peace-making, community concern and reputation caring, and awareness of and response to the social rules of the group. As a social primate species we evolved the capacity for positive moral values because they enhance the survival of both family and community. Evolution created these values in us, and religion identified them as important in order to accentuate them. “The following proposition seems to me in a high degree probable,” Darwin theorized in The Descent of Man (1871, 1:71-72), “namely, that any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts, the parental and filial affections being here included, would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience, as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well, or nearly as well developed, as in man.” The evolution of the moral sense was a stepwise process, “a highly complex sentiment, having its first origin in the social instinct, largely guided by the approbation of our fellow-men, ruled by reason, self-interest, and in later times by deep religious feelings, confirmed by instruction and habit, all combined, constitute our moral sense and conscience.”

- Evolution explains evil, original sin, and the Christian model of human nature.

We may have evolved to be moral angels, but we are also immoral beasts. Whether you call it evil or original sin, humans have a dark side. Individuals in our evolutionary ancestral environment needed to be both cooperative and competitive, for example, depending on the context. Cooperation leads to more successful hunts, food sharing, and group protection from predators and enemies. Competition leads to more resources for oneself and family, and protection from other competitive individuals who are less inclined to cooperate, especially those from other groups. Thus, we are by nature, cooperative and competitive, altruistic and selfish, greedy and generous, peaceful and bellicose; in short, good and evil. Moral codes, and a society based on the rule of law, are necessary not just to accentuate the positive, but especially to attenuate the negative side of our evolved nature. Christians would find little to disagree with in this observation by Thomas Henry Huxley, Darwin’s chief defender of evolutionary theory in the nineteenth century, in his 1894 book Evolution and Ethics: “Let us understand, once for all, that the ethical process of society depends, not on imitating the cosmic process, still less in running away from it, but in combating it.”

- Evolution explains the origin of Christian morality.

Religions designed moral codes based on our evolved natures. For the first 90,000 years of our existence as fully modern humans, our ancestors lived in small bands of tens to hundreds of individuals. In the last 10,000 years, these bands evolved into tribes of thousands; chiefdoms of tens of thousands; states of hundreds of thousands; and empires of millions. With those increased populations came new social technologies for governance and conflict resolution: politics and religion.

The moral emotions, such as guilt and shame, pride and altruism, evolved in those tiny bands of 100 to 200 people as a form of social control and group cohesion. One means of accomplishing this was through reciprocal altruism—“I’ll scratch your back if you’ll scratch mine.” But as Madison noted, men are not angels. People defect from informal agreements and social contracts. In the long run, reciprocal altruism works only when you know who will cooperate and who will defect. This information is gathered in various ways, including through stories about other people—more commonly known as gossip. Most gossip is about relatives, close friends, those in our immediate sphere of influence and members of the community or society who have high social status. It is here we find our favorite subjects of gossip: sex, generosity, cheating, aggression, social status and standings, births and deaths, political and religious commitments, and the various nuances of human relations, particularly friendships and alliances.

When bands and tribes gave way to chiefdoms and states, religion developed as a social institution to accentuate amity and attenuate enmity. It did so by encouraging altruism and selflessness, discouraging excessive greed and selfishness, and especially by revealing the level of commitment to the group through social events and religious rituals. If I see you every week participating in our religion’s activities and following the prescribed rituals, this is signal that you can be trusted. As organizations with codified moral rules and the power to enforce the rules and punish their transgressors, religion and government responded to a need.

Consider the biblical command to “Love thy neighbor.” In the Paleolithic social environment in which our moral sentiments evolved, one’s neighbors were family, extended family, and community members who were either related to or knew well to everyone else. To help others was to help oneself. In chiefdoms, states, and empires, the decree meant one’s immediate in-group. Out-groups were not included. This explains the seemingly paradoxical nature of Old Testament morality, where on one page high moral principles of peace, justice and respect for people and property are promulgated, and on the next page killing, raping, and pillaging people who are not one’s “neighbors” are endorsed. The cultural expression of this in-group morality is not restricted to any one religion, nation, or people. It is a universal human trait common throughout history, from the earliest bands and tribes to modern nations and empires. Christian morality was designed to help us overcome these natural tendencies.

- Evolution explains specific Christian moral precepts.

Much of Christian morality has to do with human relationships, most notably sexual fidelity and truth-telling, because the violation of these causes a severe breakdown in trust, and once trust is gone there is no foundation on which to build a family or a community. Evolution explains why.

We evolved as pair-bonded primates for whom monogamy is the norm (or, at least, serial monogamy—a sequence of monogamous marriages). Adultery is a violation of a monogamous relationship and there is copious scientific data showing how destructive adulterous behavior is to a monogamous relationship. (In fact, one of the reasons that serial monogamy best describes the mating behavior of our species is that adultery typically destroys a relationship, forcing couples to split up and start over with someone new.) This is why most religions are unequivocal on the subject. Consider Deuteronomy 22:22: “If a man is found lying with the wife of another man, both of them shall die, the man who lay with the woman, and the woman; so you shall purge the evil from Israel.” Most religions decree adultery to be immoral, but this is because evolution made it immoral. How?

Adultery does have some evolutionary benefits. For the male, sexual promiscuity increases the probability of his genes making it into the next generation. For the female, it is a chance to trade up for better genes, greater resources, and higher social status. The evolutionary hazards of adultery, however, often outweigh the benefits, as David Buss detailed in two books, The Dangerous Passion and When Men Behave Badly. For males, revenge by the adulterous woman’s husband can be extremely dangerous, if not deadly—some nontrivial percentage of homicides involve love triangles. And while getting caught by one’s own wife is not likely to result in death, it can result in loss of contact with children, loss of family and security, and risk of sexual retaliation, thus decreasing the odds of one’s mate bearing one’s own offspring. For females, being discovered by the adulterous man’s wife involves little physical risk, but getting caught by one’s own husband can and often does lead to extreme physical abuse and even death (the primary perpetrator of homicide against women is an intimate partner). So evolutionary theory explains the origins and rationale behind the religious precept against adultery.

Likewise for truth-telling and lying. Truth telling is vital for building trust in human relations, so lying is a sin. Unfortunately, research shows that all of us lie every day, but most of these are so-called “little white lies,” where we might exaggerate our accomplishments, or lies of omission, where information is omitted to spare someone’s feelings or save someone’s life—if an abusive husband inquires whether you are harboring his terrified wife it would be immoral for you to answer truthfully. Such lies are usually considered amoral. Big lies, however, lead to the breakdown of trust in personal and social relationships, and these are considered immoral. As Robert Trivers argues in The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, evolution created a system of deception detection because of the importance of trusting social relations to our survival and fecundity. Although we are not perfect lie detectors (and thus you can fool some of the people some of the time), if you spend enough time and have enough interactions with someone, their honesty or dishonesty will be revealed, either through direct observation or by indirect gossip from other observers.

Ultimately, as I argued in The Science of Good and Evil, it is not enough to fake doing the right thing in order to fool our fellow group members, because although we are good liars, we are also good lie detectors. The best way to convince others that you are a moral person is not to fake being a moral person but to actually be a moral person. Don’t just pretend to do the right thing, do the right thing. Such moral sentiments evolved in our Paleolithic ancestors living in small communities. Subsequently, religion identified these sentiments, labeled them, and codified rules about them.

- Evolution explains conservative free market economics.

Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection is precisely parallel to Adam Smith’s theory of the invisible hand. Darwin showed how complex design and ecological balance were unintended consequences of individual competition among organisms. Smith showed how national wealth and social harmony were unintended consequences of individual competition among people. The natural economy mirrors the artificial economy. Conservatives embrace free market capitalism. In fact, they are against excessive top-down governmental regulation of the economy because they understand that it is a complex emergent property of bottom-up design in which individuals are pursuing their own self-interest without awareness of the larger consequences of their actions. As Smith wrote in his 1776 book On the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

By allowing individuals to follow their natural inclination to pursue their self-love, the country as a whole will prosper, almost as if the entire system were being directed by…yes…an invisible hand. It is here where we find the one and only use of the metaphor in The Wealth of Nations:

Every individual is continually exerting himself to find out the most advantageous employment for whatever capital he can command. … He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. He intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

This brings us back to Darwin and his description of what happens in nature when organisms pursue their self-love, with no cognizance of the unintended consequences of their behavior:

It may be said that natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinising, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving and adding up all that is good; silently and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, at the improvement of each organic being in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life. We see nothing of these slow changes in progress, until the hand of time has marked the long lapses of ages, and then so imperfect is our view into long past geological ages, that we only see that the forms of life are now different from what they formerly were.

By providing a scientific foundation for the core values shared by most Christians and conservatives, the theory of evolution may be fully embraced along with the rest of science. When it is, the needless conflict between science and religion—currently being played out in curriculum committees and public courtrooms over evolution and creationism—must end now, or else, as the book of Proverbs (11:29) warned:

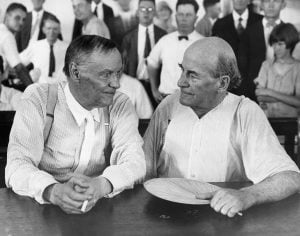

“He that troubleth his own house shall inherit the wind.”

Clarence Darrow, a famous Chicago lawyer, and William Jennings Bryan, defender of Fundamentalism, have a friendly chat in a courtroom during the Scopes evolution trial. Darrow defended John T. Scopes, a biology teacher, who decided to test the new Tenessee law banning the teaching of evolution. Bryan took the stand for the prosecution as a bible expert. The trial in 1925 ended in conviction of Scopes.