Category: Religion

The Problem With Miracles, by Sam Harris

Keeping the Folks in the Pews in the Dark

By David Madison at 10/21/2022

Here’s the link to this article.

What the church doesn’t want them to think about

Worship services are a form of show business, at which some Christian brands excel especially. How much does the Vatican spend every year on its worship costumes alone? But most denominations, while not so extravagant, do their best to “put on the show,” which includes music, liturgy, ritual, props, sets—those stained-glass depictions of Bible stories—and the trained actors, i.e., the clergy. All this is designed to promote the beliefs and doctrines of each denomination. But there are so many different denominations: who is getting Christianity right? Is there any denomination that urges its followers to look beyond the liturgies? What’s behind it all? What are the origins of the beliefs celebrated in liturgies?

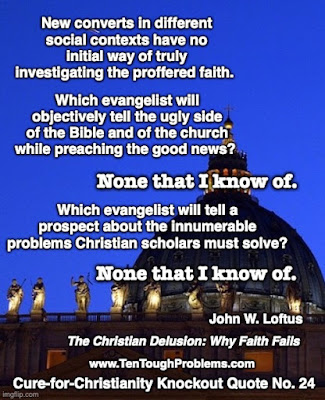

John Loftus, in The Christian Delusion: Why Faith Fails, has correctly noted how the church—of whatever brand—tries to win and keep converts:

“New converts in different social contexts have no initial way of truly investigating the proffered faith. Which evangelist will objectively tell the ugly side of the Bible and of the church while preaching the good news? None that I know of. Which evangelist will tell a prospect about the innumerable problems Christian scholars must solve? None that I know of.” (p. 90)

Indeed, it might be argued that the worship spectacle—it really is a show—is meant to divert attention from truly distressing realities that are best ignored—for the sake of keeping faith intact.

Here are four of these distressing realities:

1. The Bible doesn’t qualify as divinely inspired

The Bible has been hyped for centuries as a source of information about a god. A splendid edition of the Bible is commonly found on the church altar, and no Christian home would be complete without at least one copy. Presidents are sworn in using the Bible as a prop. One Christian sect has footed the bill for placing more than a billion copies of it in hotel rooms. It has been translated into hundreds of languages, not doubt because of Jesus-script in Matthew 28:19, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations…”

Yet with all this, how embarrassing that many Christians pay so little attention to it, maybe because they’ve tried reading it, and given up. They grasp—but would rarely admit—that Hector Avalos’ analysis is correct: going line by line, 99% of the Bible would not be missed. After trying to wade through much of the Old Testament or the letters of the apostle Paul, they’re happy with the feel-good verses read from the pulpit. Moreover, they are largely unaware that intense scholarly study of the Bible—for the last two centuries—has revealed how deficient the Bible is from the perspectives of morality, history, or even what might reasonably be called sane religion.

This is the distressing reality, for which I make a full case in my essay, “Five Inconvenient Truths that Falsify Biblical Revelation,” in John Loftus’ 2019 anthology, The Case Against Miracles. I’ll offer one specific example here. In January 2018, on this blog, I published an article, Getting the Gospels Off on the Wrong Foot, in which I discussed several bizarre features of Mark’s gospel—specifically about Jesus. Hence my warning to those Christians who want to believe that Mark’s gospel was divinely inspired: “If you accept the Jesus of Mark’s gospel, you are well on the way to full-throttle crazy religion. No slick excuses offered by priests and pastors—none of their pious

posturing about ‘our Lord and Savior’—can change that fact.”

Christian apologists have written countless books and articles trying to rescue the Bible, to hold on to it as divinely inspired scripture. For the most part, they convince only each other.

2. Christian origins scuttle its claim to be the One True Religion

It is common to celebrate the heroism and determination of the apostle Paul, especially as he is portrayed in the Book of Acts. But then we hit a brick wall: this apostle, whose writings are the first we have about Jesus Christ, never met or knew Jesus—and bragged that he didn’t learn anything about Jesus from those who had followed him: “For I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that the gospel that was proclaimed by me is not of human origin, for I did not receive it from a human source, nor was I taught it, but I received it through a revelation of Jesus Christ.” (Galatians 1:11-12) Paul had no problem claiming it was “a revelation,” but we can be properly skeptical about getting messages from the spiritual realm: where is the reliable, verifiable data that this actually happens? A better explanation is that Paul suffered from hallucinations. So this is not good: the Christian religion received a major primary boost from the hallucinations of a man who never met Jesus. This must qualify as a distressing reality.

Nor can Christians fall back on the gospels as a firm anchor for the truth about Jesus. There is scant evidence that they were written by eyewitnesses. The broad consensus among Christian scholars—outside of fundamentalist/evangelical circles—is that the gospels were written after the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 CE during the First Jewish-Roman War. This ferocious conflict brought widespread devastation; it is highly improbable that anyone in the original Jesus-sect, i.e., eyewitnesses, would have survived. Thus one of the agonizing dilemmas in New Testament scholarship: there is no way to verify any of the words and deeds of Jesus reported in the gospels. Especially since the gospels read so much like fantasy literature. Devout readers may think this is okay—after all, they believe in miracles. But each miracle story, each bit of folklore and magical thinking, forces historians to concede that the gospels fail as history. They qualify rather as propaganda literature for the early Jesus cult. And they worked so well in this capacity for centuries, until critical, skeptical analysis of the gospels began to take over.

The fact that the gospels were written in Greek points to even more complications in figuring out Christian origins. Dennis MacDonald has shown, in several of his books, that the gospel writers were influenced by Greek literature in creating their stories about Jesus. Thus it’s no surprise that themes common in other religions were grafted onto the Jesus narratives, e.g., a hero or divine son born of a virgin, a dying-and-rising god bringing salvation to followers; so many of the wonders attributed to Jesus are similar to miracle folklore found in other religious traditions.

Yet all these factors that influenced the birth and evolution of Christianity remain outside the awareness of those who show up for church—for the worship experience. Many priests and preachers may be in the dark themselves. They were trained to “spread the gospel,” not to encourage probing, skepticism, and doubt. The literature on the complex origins of the Christian faith is now vast; scholars have been studying it for a long time. But almost none of this has filtered down to the laity.

3. Christians have fought and killed each other over theological differences

What a sorry history this is, a distressing reality indeed. Even in the New Testament itself, we find the beginnings of Christian dissention. The apostle Paul was blunt: “But when Cephas [Peter] came to Antioch, I opposed him to his face because he stood self-condemned…” (Galatians 2:11) And in I Corinthians 1:10-13 we read:

“Now I appeal to you, brothers and sisters, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that all of you be in agreement and that there be no divisions among you but that you be knit together in the same mind and the same purpose. For it has been made clear to me by Chloe’s people that there are quarrels among you, my brothers and sisters. What I mean is that each of you says, ‘I belong to Paul,’ or ‘I belong to Apollos,’ or ‘I belong to Cephas,’ or ‘I belong to Christ.’ Has Christ been divided?”

This tendency of Christians to disagree has resulted in the endless—and continuing—splintering of this religion, with now well over 30,000 different denominations, divisions, sects, and cults: because they cannot agree on theology and worship practice. Which doesn’t seem to bother the faithful, and is even piously denied: “In Christ there is no east or west, in him no south or north, but one great fellowship of love throughout the whole wide earth.” (Hymn lyrics by John Oxenham, 1908)

Philip Jenkins came up with one of the best titles ever: Jesus Wars: How Four Patriarchs, Three Queens, and Two Emperors Decided What Christians Would Believe for the Next 1,500 Years. (2010) This is one of his observations: “By the year 500 or so, the churches were in absolute doctrinal disarray, a state of chaos that might seem routine to a modern American denomination, but which in the context of the time

seemed like satanic anarchy.” (p. 242)

The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) is an appalling example (four to eight million dead) of Christians killing other Christians. Consider also World War I, Christian nations locked in mutual slaughter for four years.

One more example—a less terrifying one—of Christians not being able to get along. In this case, Catholics. There are Catholic women who want to become priests, convinced this is their vocation because of they’ve been called to it by the Holy Spirit. But the patriarchy will have none of it, saying, in effect, that the holy-spirit-experience of these devout women is not valid. The male priests, anchored in their own theological certainties, don’t want to admit women to their fellowship of love.

4. Small and epic episodes of horrendous suffering cancel belief in a good, powerful god

This is a distressing reality that is perhaps ignored the most. The spectacle of worship is a way for the devout to hold on to their belief that the Cosmos is friendly, that a caring father-god is accessible, and can be influenced by flattery, i.e., “How great thou art!” “Hallowed be thy name!” etc. Even a little reflection shows that this doesn’t bring the desired results. We live in a dangerous world, and even the most fervent believers are not exempt from ssuffering. Just look at the way the world works—if you’re religious, look at the way your god allows the world to work: school shootings, church shootings (one in particular, in which hundreds of women and children were machine-gunned to death), endless warfare for millennia (all that aggression…god couldn’t have done better designing the human brain?), thousands of genetic diseases, the agony of mental illness, plagues, pandemics, cancers; our brutal planet, i.e., earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, floods, tornadoes, wildfires.

The faithful need to reflect on the implications of these horrors. But critical thinking doesn’t come easily. We’ve all heard the stories of houses burning down, people killed, but wow: a Bible was left untouched by the flames. A miracle! A plane crashes, hundreds die, but wow one person somehow survived. A miracle! Such nonsense is encouraged by clerical explanations for small and epic episodes of horrendous suffering:

“God works in mysterious ways.”

“God has a bigger plan that we don’t know about.”

These are guesses, speculation. To take them seriously we need to know where we can find the reliable, verifiable, objective data upon which they’re based. No such luck, these are evasive tactics, cowardly dodges: “We don’t want to think about issues that might damage our faith.” And so many of the laity follow. Other excuses are even worse:

“God is testing us, punishing us.”

Of course, the clergy can turn to the Bible to back up this excuse. Bible-god threatens repeated—in both the Old and New Testaments—to destroy people for their sins. Believers who nod approval apparently don’t notice their descent into bad theology, oblivious to a god who qualifies as a moral monster. On the other hand, I suspect that some church folks shy away from Bible reading because the abusive theology is all too obvious, e.g., in this Jesus-script: “I tell you, on the day of judgment you will have to give an account for every careless word you utter…” (Matthew 12:36)

The ministry requires certain skills for spreading the good news, preaching the standard creeds, but at the same time suppressing curiosity: “It’s better not to think about the things we don’t want you to think about. Take what we say on faith—please.”

David Madison was a pastor in the Methodist Church for nine years, and has a PhD in Biblical Studies from Boston University. He is the author of two books, Ten Tough Problems in Christian Thought and Belief: a Minister-Turned-Atheist Shows Why You Should Ditch the Faith (2016; 2018 Foreword by John Loftus) and Ten Things Christians Wish Jesus Hadn’t Taught: And Other Reasons to Question His Words (2021). His YouTube channel is here. He has written for the Debunking Christianity Blog since 2016.

The Cure-for-Christianity Library©, now with more than 500 titles, is here. A brief video explanation of the Library is here.

Why Even Conservative Christians Should Accept Evolution: Blog Anniversary Guest Post by Michael Shermer (part 2)

September 8, 2022

Here is the link to this article.

For several months now I have been posting Guest Posts that were generoulsly provided by others in honor of the blog’s tenth anniversary. These posts have been wide-ranging in their content and the intriguing , each pbased on the posters’ unique backgrounds and expertise. This now is the final one in the series, the second of two posts by Michael Shermer, to continue what he was saying in his post of Sept. 3.

This one is particularly significant. Why is it in conservative Christians’ (and everyone else’s) own best interest to accept evolution as a reality of the past? He makes some compelling points. Read and see!

*************************

To counter the doubts I mentioned in my previous post, I argue that, in fact, Christians and conservatives should accept the theory of evolution for at least eight reasons (again, for brevity, truncated here):

- Evolution happened.

The theory describing how evolution happened is one of the most well-founded in all of science. Christians and conservatives embrace the value of truth-seeking as much as non-Christians and liberals do, so evolution should be accepted by everyone because it is true. In this sense, evolution is no different than any other scientific theory already fully accepted by both Christians and conservatives, such as Big Bang cosmology, heliocentrism, gravity, continental drift and plate tectonics, the germ theory of disease, the genetic basis of heredity, the aerodynamics of flight, and more.

- Evolution makes for good theology.

Christians believe in a God who is omniscient, omnipotent, and eternal. Compared to eternity, what difference does it make when God created the universe—10,000 years ago or 10,000,000,000 years ago? The glory of the creation commands reverence regardless of how many zeroes there are in the age. And compared to omniscience and omnipotence, what difference does it make how God created life—spoken word or natural forces? The grandeur of life’s complexity elicits awe regardless of what creative processes were employed. Christians should embrace evolutionary theory (and cosmology) for what it has done to reveal the magnificence of the divinity in a depth and detail unmatched by ancient texts. Darwin himself made this argument in response to his critics in the 2nd edition of On the Origin of Species:

I see no good reason why the views given in this volume should shock the religious feeling of any one. It is satisfactory, as showing how transient such impressions are, to remember that the greatest discovery ever made by man, namely, the law of the attraction of gravity, was also attacked by Leibnitz, ‘as subversive of natural, and inferentially of revealed, religion.’ A celebrated author and divine has written to me that ‘he has gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of the Deity to believe that He created a few original forms, capable of self-development into other and needful forms, as to believe that He required a fresh act of creation to supply the voids caused by the actions of His laws.

Surely God has more important things to do than to track the fall of every sparrow (Matthew 10:29).

- Intelligent Design makes for bad theology.

ID creationism reduces God to an artificer, a divine watchmaker piecing together life out of available parts in a cosmic warehouse. If God is a being in space and time, it means that He is restrained by the laws of nature and the contingencies of chance, just like all other being of this world. An omniscient and omnipotent God must be above such constraints and not subject to law and chance. God as creator of heaven and earth and all things visible and invisible would need necessarily to be outside such created objects. If He is not, then God is like us, only smarter and more powerful; but not omniscient and omnipotent. Calling God a watchmaker is delimiting.

- Evolution explains Christian family values and social harmony.

The following characteristics are shared by humans and other social mammals: attachment and bonding, cooperation and mutual aid, sympathy and empathy, direct and indirect reciprocity, altruism and reciprocal altruism, conflict resolution and peace-making, community concern and reputation caring, and awareness of and response to the social rules of the group. As a social primate species we evolved the capacity for positive moral values because they enhance the survival of both family and community. Evolution created these values in us, and religion identified them as important in order to accentuate them. “The following proposition seems to me in a high degree probable,” Darwin theorized in The Descent of Man (1871, 1:71-72), “namely, that any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts, the parental and filial affections being here included, would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience, as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well, or nearly as well developed, as in man.” The evolution of the moral sense was a stepwise process, “a highly complex sentiment, having its first origin in the social instinct, largely guided by the approbation of our fellow-men, ruled by reason, self-interest, and in later times by deep religious feelings, confirmed by instruction and habit, all combined, constitute our moral sense and conscience.”

- Evolution explains evil, original sin, and the Christian model of human nature.

We may have evolved to be moral angels, but we are also immoral beasts. Whether you call it evil or original sin, humans have a dark side. Individuals in our evolutionary ancestral environment needed to be both cooperative and competitive, for example, depending on the context. Cooperation leads to more successful hunts, food sharing, and group protection from predators and enemies. Competition leads to more resources for oneself and family, and protection from other competitive individuals who are less inclined to cooperate, especially those from other groups. Thus, we are by nature, cooperative and competitive, altruistic and selfish, greedy and generous, peaceful and bellicose; in short, good and evil. Moral codes, and a society based on the rule of law, are necessary not just to accentuate the positive, but especially to attenuate the negative side of our evolved nature. Christians would find little to disagree with in this observation by Thomas Henry Huxley, Darwin’s chief defender of evolutionary theory in the nineteenth century, in his 1894 book Evolution and Ethics: “Let us understand, once for all, that the ethical process of society depends, not on imitating the cosmic process, still less in running away from it, but in combating it.”

- Evolution explains the origin of Christian morality.

Religions designed moral codes based on our evolved natures. For the first 90,000 years of our existence as fully modern humans, our ancestors lived in small bands of tens to hundreds of individuals. In the last 10,000 years, these bands evolved into tribes of thousands; chiefdoms of tens of thousands; states of hundreds of thousands; and empires of millions. With those increased populations came new social technologies for governance and conflict resolution: politics and religion.

The moral emotions, such as guilt and shame, pride and altruism, evolved in those tiny bands of 100 to 200 people as a form of social control and group cohesion. One means of accomplishing this was through reciprocal altruism—“I’ll scratch your back if you’ll scratch mine.” But as Madison noted, men are not angels. People defect from informal agreements and social contracts. In the long run, reciprocal altruism works only when you know who will cooperate and who will defect. This information is gathered in various ways, including through stories about other people—more commonly known as gossip. Most gossip is about relatives, close friends, those in our immediate sphere of influence and members of the community or society who have high social status. It is here we find our favorite subjects of gossip: sex, generosity, cheating, aggression, social status and standings, births and deaths, political and religious commitments, and the various nuances of human relations, particularly friendships and alliances.

When bands and tribes gave way to chiefdoms and states, religion developed as a social institution to accentuate amity and attenuate enmity. It did so by encouraging altruism and selflessness, discouraging excessive greed and selfishness, and especially by revealing the level of commitment to the group through social events and religious rituals. If I see you every week participating in our religion’s activities and following the prescribed rituals, this is signal that you can be trusted. As organizations with codified moral rules and the power to enforce the rules and punish their transgressors, religion and government responded to a need.

Consider the biblical command to “Love thy neighbor.” In the Paleolithic social environment in which our moral sentiments evolved, one’s neighbors were family, extended family, and community members who were either related to or knew well to everyone else. To help others was to help oneself. In chiefdoms, states, and empires, the decree meant one’s immediate in-group. Out-groups were not included. This explains the seemingly paradoxical nature of Old Testament morality, where on one page high moral principles of peace, justice and respect for people and property are promulgated, and on the next page killing, raping, and pillaging people who are not one’s “neighbors” are endorsed. The cultural expression of this in-group morality is not restricted to any one religion, nation, or people. It is a universal human trait common throughout history, from the earliest bands and tribes to modern nations and empires. Christian morality was designed to help us overcome these natural tendencies.

- Evolution explains specific Christian moral precepts.

Much of Christian morality has to do with human relationships, most notably sexual fidelity and truth-telling, because the violation of these causes a severe breakdown in trust, and once trust is gone there is no foundation on which to build a family or a community. Evolution explains why.

We evolved as pair-bonded primates for whom monogamy is the norm (or, at least, serial monogamy—a sequence of monogamous marriages). Adultery is a violation of a monogamous relationship and there is copious scientific data showing how destructive adulterous behavior is to a monogamous relationship. (In fact, one of the reasons that serial monogamy best describes the mating behavior of our species is that adultery typically destroys a relationship, forcing couples to split up and start over with someone new.) This is why most religions are unequivocal on the subject. Consider Deuteronomy 22:22: “If a man is found lying with the wife of another man, both of them shall die, the man who lay with the woman, and the woman; so you shall purge the evil from Israel.” Most religions decree adultery to be immoral, but this is because evolution made it immoral. How?

Adultery does have some evolutionary benefits. For the male, sexual promiscuity increases the probability of his genes making it into the next generation. For the female, it is a chance to trade up for better genes, greater resources, and higher social status. The evolutionary hazards of adultery, however, often outweigh the benefits, as David Buss detailed in two books, The Dangerous Passion and When Men Behave Badly. For males, revenge by the adulterous woman’s husband can be extremely dangerous, if not deadly—some nontrivial percentage of homicides involve love triangles. And while getting caught by one’s own wife is not likely to result in death, it can result in loss of contact with children, loss of family and security, and risk of sexual retaliation, thus decreasing the odds of one’s mate bearing one’s own offspring. For females, being discovered by the adulterous man’s wife involves little physical risk, but getting caught by one’s own husband can and often does lead to extreme physical abuse and even death (the primary perpetrator of homicide against women is an intimate partner). So evolutionary theory explains the origins and rationale behind the religious precept against adultery.

Likewise for truth-telling and lying. Truth telling is vital for building trust in human relations, so lying is a sin. Unfortunately, research shows that all of us lie every day, but most of these are so-called “little white lies,” where we might exaggerate our accomplishments, or lies of omission, where information is omitted to spare someone’s feelings or save someone’s life—if an abusive husband inquires whether you are harboring his terrified wife it would be immoral for you to answer truthfully. Such lies are usually considered amoral. Big lies, however, lead to the breakdown of trust in personal and social relationships, and these are considered immoral. As Robert Trivers argues in The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life, evolution created a system of deception detection because of the importance of trusting social relations to our survival and fecundity. Although we are not perfect lie detectors (and thus you can fool some of the people some of the time), if you spend enough time and have enough interactions with someone, their honesty or dishonesty will be revealed, either through direct observation or by indirect gossip from other observers.

Ultimately, as I argued in The Science of Good and Evil, it is not enough to fake doing the right thing in order to fool our fellow group members, because although we are good liars, we are also good lie detectors. The best way to convince others that you are a moral person is not to fake being a moral person but to actually be a moral person. Don’t just pretend to do the right thing, do the right thing. Such moral sentiments evolved in our Paleolithic ancestors living in small communities. Subsequently, religion identified these sentiments, labeled them, and codified rules about them.

- Evolution explains conservative free market economics.

Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection is precisely parallel to Adam Smith’s theory of the invisible hand. Darwin showed how complex design and ecological balance were unintended consequences of individual competition among organisms. Smith showed how national wealth and social harmony were unintended consequences of individual competition among people. The natural economy mirrors the artificial economy. Conservatives embrace free market capitalism. In fact, they are against excessive top-down governmental regulation of the economy because they understand that it is a complex emergent property of bottom-up design in which individuals are pursuing their own self-interest without awareness of the larger consequences of their actions. As Smith wrote in his 1776 book On the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.

By allowing individuals to follow their natural inclination to pursue their self-love, the country as a whole will prosper, almost as if the entire system were being directed by…yes…an invisible hand. It is here where we find the one and only use of the metaphor in The Wealth of Nations:

Every individual is continually exerting himself to find out the most advantageous employment for whatever capital he can command. … He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. He intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

This brings us back to Darwin and his description of what happens in nature when organisms pursue their self-love, with no cognizance of the unintended consequences of their behavior:

It may be said that natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinising, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving and adding up all that is good; silently and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, at the improvement of each organic being in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life. We see nothing of these slow changes in progress, until the hand of time has marked the long lapses of ages, and then so imperfect is our view into long past geological ages, that we only see that the forms of life are now different from what they formerly were.

By providing a scientific foundation for the core values shared by most Christians and conservatives, the theory of evolution may be fully embraced along with the rest of science. When it is, the needless conflict between science and religion—currently being played out in curriculum committees and public courtrooms over evolution and creationism—must end now, or else, as the book of Proverbs (11:29) warned:

“He that troubleth his own house shall inherit the wind.”

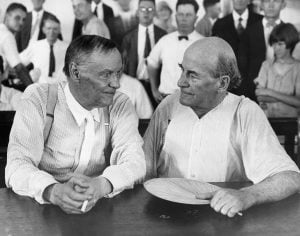

Clarence Darrow, a famous Chicago lawyer, and William Jennings Bryan, defender of Fundamentalism, have a friendly chat in a courtroom during the Scopes evolution trial. Darrow defended John T. Scopes, a biology teacher, who decided to test the new Tenessee law banning the teaching of evolution. Bryan took the stand for the prosecution as a bible expert. The trial in 1925 ended in conviction of Scopes.

Why Christians and Conservatives Should Accept Evolution: Blog Anniversary Guest Post by Michael Shermer (part 1)

September 3, 2022

Here’s the link to this article.

I have been publishing guest posts in celebration of the blog’s tenth anniversary, and am pleased to conclude the series now with two posts by Michael Shermer, whom many of you will know from his writings and media appearances discussing (especially) religion and science. Michael was a one-time committed fundamentalist turned outspoken skeptic. Here is the first of his two-parter, on an issue of particular cultural and religious importance.

US public acceptance of evolution is growing but is still low compared to other countries. Why? Religion and politics. Here’s why that need not be.

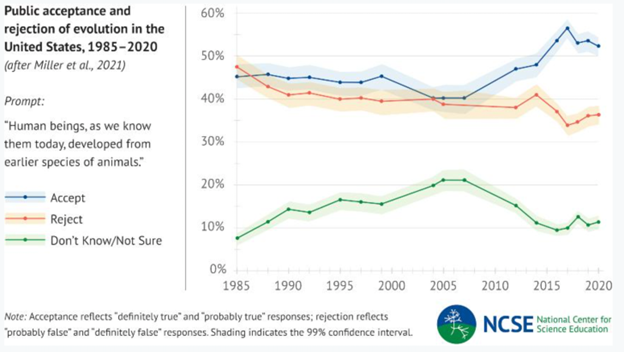

As a career-long student of the century-long evolution-creationism debate I was encouraged to read the results of a new study on “Public Acceptance and Rejection of Evolution in the United States, 1985-2020” by Jon Miller, Eugenie Scott, Mark Ackerman, and Belén Laspra, published in the journal Public Understanding of Science. “Using data from a series of national surveys collected over the last 35 years, we find that the level of public acceptance of evolution has increased in the last decade after at least two decades in which the public was nearly evenly divided on the issue,” the authors write. That sounds encouraging, and the uptick of the blue line of acceptance and downward slope of the orange line of rejection in this graph appears encouraging, until one glances over at the vertical axis showing that progress here is defined as breaking the 50 percent barrier! That’s not especially encouraging for a robust science that began 162 years ago with the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and accepted by 97 percent of all scientists.

What is the cause in the recent increase (however modest) in the acceptance of the theory? According to the study’s authors:

A structural equation model indicates that increasing enrollment in baccalaureate-level programs, exposure to college-level science courses, a declining level of religious fundamentalism, and a rising level of civic scientific literacy are responsible for the increased level of public acceptance.

Those of us in academia, and especially in the science education business, should find this especially encouraging, but I want to drill down into that variable of “religious fundamentalism,” which the authors defined and quantified as belief in a personal God who hears prayers, reading the Bible as literal truth, frequency of church attendance, frequency of prayer, and agreement with the statement “We depend too much on science and not enough on faith.” There was an inverse correlation between religious fundamentalism and acceptance of evolution: 32 percent acceptance on the high end of the scale compared 91 percent on the lowest end of the scale (and 54 percent of the entire sample). That 30 percent of Americans self-identify as religious fundamentalists goes a long way to explaining their doubt. As does their political affiliation. While 83 percent of liberal Democrats accept the theory of evolution, the researchers found that only 34 percent of conservative Republicans do so.

Why do Christians and conservatives doubt evolution? My 2006 book Why Darwin Matters (my only book with full frontal nudity) attempts to answer this question. For brevity here, I will outline four reasons:

-

-

-

-

- Belief that evolution is a threat to specific religious tenets. If one believes that the world was created within the past 10,000 years, that will be in direct conflict with the geological evidence for a 4.6 billion-year old Earth. If one insists on the findings of science squaring true with religious doctrines, this can lead to conflict between science and religion.

- Misunderstanding of evolutionary theory. Many cognitive studies show, such as those by Andrew Shtulman and others in his book Scienceblind: Why Our Intuitive Theories About the World Are So Often Wrong, that most people—both religious believers and secularists alike—have a poor understanding of the theory, mixing in some Lamarckian notions of the inheritance of acquired characteristics (giraffes got their long necks by stretching), a misunderstanding of population genetics, and a fumbled explanation of what, exactly, natural selection is selecting for (not the good of the species or the group, not future environments, not structural or cognitive progress).

- The fear that evolution degrades our humanity. After Copernicus toppled the pedestal of our cosmic centrality, Darwin delivered the coup de grace by revealing us to be “mere” animals, subject to the same natural laws and historical forces as all other animals.

- The equation of evolution with ethical nihilism and moral degeneration. This sentiment was expressed by the neo-conservative social commentator Irving Kristol in 1991: “If there is one indisputable fact about the human condition it is that no community can survive if it is persuaded—or even if it suspects—that its members are leading meaningless lives in a meaningless universe.” Similar fears were raised by Nancy Pearcey, a fellow of the Discovery Institute in a briefing on Intelligent Design before a House Judiciary Committee of the United States Congress. She cited a popular song urging “you and me, baby, ain’t nothing but mammals so let’s do it like they do on the Discovery Channel.” Pearcey went on to claim that since the U.S. legal system is based on moral principles, the only way to generate ultimate moral grounding is for the law to have an “unjudged judge,” an “uncreated creator.”

-

-

-

Faith vs. Fact, by Jerry Coyne. Reading Session #3 (continuing Chapter 1, The Problem)

This is a great book. Eye-opening, especially to those who’ve never considered the incompatibility of science and religion.

I encourage you to watch my computer screen, listen, and think as I read aloud the words written by the brilliant evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne.

Click the link below to begin Reading Session #3 (sorry, but I think I refer to this session as Session #2). This session starts at Kindle Page 11, Location 500.

Faith vs. Fact, by Jerry Coyne. Reading Session #2 (Chapter 1, The Problem).

This is a great book. Eye-opening, especially to those who’ve never considered the incompatibility of science and religion.

I encourage you to watch my computer screen, listen, and think as I read aloud the words written by the brilliant evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne.

Click the link below to begin Reading Session #1.

Faith vs. Fact, by Jerry Coyne. Reading Session #1 (Preface: The Genesis of this Book).

This is a great book. Eye-opening, especially to those who’ve never considered the incompatibility of science and religion.

I encourage you to watch my computer screen, listen, and think as I read aloud the words written by the brilliant evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne.

Click the link below to begin Reading Session #1.

Does Mark’s Gospel Implicitly Deny the Virgin Birth?

The following is interesting and addresses one of two questions that, if the answer is no, virtually destroys the foundation of what Southern Baptist fundamentalists believe. The first question is, ‘was Jesus born to a virgin?’ The second (not addressed here) is simply, ‘did Jesus resurrect to life on the third day?’

Please take note of the following well-established fact: the Gospel of Mark was the first of the four canonical gospels. It was written thirty to fourty years after Jesus’ death.

The following article strongly implies the authors of the gospels of Matthew and Luke (the second and third gospels to be written) created the virgin birth myth.

Here is the link to the titled article.

By Bart Ehrman

December 27, 2014

It is interesting that our first canonical Gospel (which is our first Gospel, whether canonical or noncanonical), Mark, does not have the story of the Virgin birth and in fact shows no clue that it is familiar with the stories of the Virgin birth. On the contrary, there are passages in Mark that appear to work against the idea that Jesus’ mother knew anything about his having had an extraordinary birth.

There is a complicated little passage in Mark 3:20-21 about Jesus’ family coming to take him out of the public eye because they thought he was crazy. It is a difficult passage to translate from the Greek, and a number of translations go out of their way to make it say something that it probably doesn’t say. The context is that Jesus has been doing extraordinary miracles, attracting enormous crowds, and raising controversy among the Jewish leaders. Jesus then chooses his disciples and they go with him into a house. And then come our verses.

In the Greek the passage literally says that “those who were beside him came forth” in order to seize him, because they were saying, EXESTH. The two problems are: who is this group that has come, and what does it meant that he EXESTH? It is widely thought among translators and interpreters – and I think this has to be right – that “those who were beside him” means “his family.” It cannot mean the disciples, because they are already with him in the house. It must be people who were personally attached to Jesus (that’s what the phrase “were beside him” means). And so that appears to leave his family members. No one else is “on his side,” as it were.

Why then did his family members come? Because they thought he was EXESTH. Whatever the word means, it can’t be good. The whole point of this section of Mark is that Jesus is finding opposition everywhere he turns, despite all the miracles he is doing. The Pharisees are against him because they don’t think he has authority to do the things he does (2:24, 3:2). They become so outraged at his activities that they team up with the Herodians to decide to kill him (3:6). The scribes are against him because they think that he has blasphemed against God (2:6) and that he does his mighty works because he is possessed by the Devil, Beelzebub (3:22). Even his family members – those who stand beside him – think that he EXESTH.

The word EXESTH literally means “to stand outside of oneself.” It is a phrase comparable to the English phrase “to be out of your mind.” In other words, it means “he has gone crazy.”

And so 3:21-22 can be translated “Now when his family heard these things they came out in order to seize him, for they were saying “He is out of his mind.”

Some translators don’t like that way of putting it, not because of any grammatical or lexical issues with the Greek, but simply because they can’t get their heads around Jesus’ family members thinking that he has gone crazy. And so, to avoid the problem, they sometimes change the translation – not because of what the Greek says, but because of what they think it ought to say. And so they translate it as saying that his family has come to take him out of the public eye because “people were saying that ‘He is beside himself.’” (Thus the RSV, for example.)

This is really taking liberties with the Greek. In Greek, the subject of a sentence is often not expressed because it can be found in the form of the verb itself. I will try to explain this simply. In English, when we write or speak a sentence that requires a pronoun (“I” “you” He” “she” “they” “Those ones” “These ones”) we actually give the pronoun. In Greek and other “inflected” languages, the pronouns are already built into the verb. So the verb is spelled differently, with a different ending, whether you want the subject to be “I” “you” “she” “we” etc. It was possible for Greek to use pronouns, of course, and it often does when it wants to place special emphasis on the subject. But in normal speech it was not necessary.

Now the rule is that if a sentence containing a verb does not have an explicit pronoun, and the subject within the sentence itself is ambiguous, then the implied subject (found in the ending of the verb) is the immediately preceding noun or pronoun (or other substantive). So that if you have a sentence that says “He jumped over the ditch,” you actually do not know who the “he” is unless you look in the preceding context and see, right before this sentence, something like, “James ran into the field.” Then you know that the “He” that is jumping over the ditch is James.

Apologies for the grammar lesson here, but it matters. In Mark 3:21, when it says “for they were saying” there is no noun or pronoun expressed to indicated who the “they” is. And so, by the rules of grammar, it almost certainly refers to the closest antecedent, which in this case is “those who were on his side,” i.e., his family. In other words, the ones who came to seize him were the ones saying that he is out of his mind.

The RSV translators were not happy with that view though, evidently because of its implications. But its implications are the very point of the passage and of this post. (As I’ll explain in just one second.) Still, not liking what the verse actually said, the RSV translators interpreted it and re-translated it so the English says something different from the Greek. Their English version adds the word “people” – not found in the Greek – to explain who, in the translators’ opinion, were saying that Jesus had gone crazy. And now what the story means is that the family of Jesus wanted to take him from the public eye because there were people out there saying that he was nuts. But that’s not what the Greek says. The Greek says that the family came to seize him because they were saying that he was nuts.

And who would be included in his family? It becomes pretty clear later in the chapter. For once again his family members come, and we’re told that it is “his mother and his brothers” (3:31) – in another interesting passage where Jesus appears to reject them in favor of his followers (3:31-34).

What does all this have to do with the Virgin birth? Mark does not narrate an account of Jesus’ birth. Mark never says a word about Jesus’ mother being a virgin. Mark does not presuppose that Jesus had an unusual birth of any kind. And in Mark (you don’t find this story in Matthew and Luke!!), Jesus’ mother does not seem to know that he is a divinely born son of God. On the contrary, she thinks he has gone out of his mind. Mark not only lacks a virgin birth story; it seems to presuppose that they never could have been a virgin birth. Or Mary would understand who Jesus is. But she does not.

It’s no wonder that when Matthew and Luke took over so many of the stories of Mark, they decided, both of them, not to take over Mark 3:20-21. They had completely different view of Jesus’ mother and his birth.