Category: Religion

Christianity’s Biggest Sins

Here’s the link to this article by David Madison.

03/03/2023

Fueled by scripture’s biggest mistakes

In the second chapter of Acts we find the story of Peter preaching about Jesus, with dramatic results: “So those who welcomed his message were baptized, and that day about three thousand persons were added” (v. 41). Most New Testament scholars grant that the Book of Acts was written decades after events depicted, all but conceding that authentic history is hard to find here; sources are not mentioned, and the case for Jesus is made primarily by quoting from the Old Testament. Moreover, the fantasy factor is pretty high, e.g., an angel helps Peter escape from prison: “Suddenly an angel of the Lord appeared. A light shone in the prison cell. The angel struck Peter on his side. Peter woke up. ‘Quick!’ the angel said. ‘Get up!’ The chains fell off Peter’s wrists” (Acts 12:7).

The early Christians were a small breakaway Jewish sect, but there’s an attempt here to exaggerate its success: three thousand were baptized when they heard Peter speak. How would an author writing decades after the “event” have been able to verify that figure? And are modern readers supposed to be impressed that three thousand people signed up because they heard the words of a preacher? Throughout the ages many cults have gathered the gullible in exactly this way.

Scripture’s First Big Mistake

But catastrophic damage has been done by this text—and many others—by positioning the Jews as the bad guys, the enemies of God and Christ. Verse 23: “…this man, handed over to you according to the definite plan and foreknowledge of God, you crucified and killed by the hands of those outside the law.” The Christians set themselves apart from Judaism by claiming that Jesus was the messiah, and it was but a small step to assume that evil was behind the denial of this status to Jesus.

This finds expression in the nasty verse in John’s gospel (8:44)—which John presents as Jesus-script, addressed to the Jews: “You are from your father the devil, and you choose to do your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning and does not stand in the truth because there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks according to his own nature, for he is a liar and the father of lies.” This is pretty bad: “You Jews, your god is the devil.”

In Paul’s letter to the Thessalonians (called I Thessalonians; II Thessalonians is widely regarded as a forgery), in chapter 2 we find these verses, 14-16:

“For you, brothers and sisters, became imitators of the churches of God in Christ Jesus that are in Judea, for you suffered the same things from your own compatriots as they did from the Jews who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets and drove us out; they displease God and oppose everyoneby hindering us from speaking to the gentiles so that they may be saved. Thus they have constantly been filling up the measure of their sins, but wrath has overtaken them at last.”

There was been debate among scholars about this text—is it an interpolation? —but there it is in the New Testament, with plenty of devout Christians over the centuries willing to help overtake Jews with wrath. This has to be counted as one of Christianity’s biggest sins, which resulted in the Holocaust. Hector Avalos makes the case for this in his essay, “Atheism Was Not the Cause of the Holocaust,” in John Loftus’ 2010 anthology, The Christian Delusion: Why Faith Fails.

He quotes Catholic historian, José M. Sánchez: “There is little question that the Holocaust had its origins in the centuries-long hostility felt by Christians against Jews.” (p. 70, in Sánchez’s 2002 book, Pious XII and the Holocaust: Understanding the Controversy)

For more on this, see the Wikipedia article, Anti-Semitism and the New Testament.

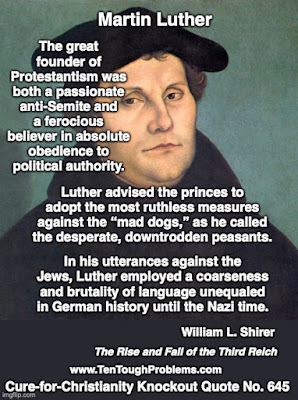

Centuries-long hostility. In his essay, Avalos provides details of Martin Luther’s ferocious hatred of Jews, and William Shirer, in his classic work, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, notes that “…in his utterances about the Jews, Luther employed a coarseness and brutality of language unequaled in German history until the Nazi time” (p. 236). This is the holy hero so revered for launching the Reformation, and for whom a major denomination is named. It would seem that far too many Christians have failed to study church history. They fail to see this horribly ugly impact of verses in the New Testament. The willing, and in many cases, enthusiastic embrace of anti-Semitism is one of Christianity’s biggest sins.

Scripture’s Second Big Mistake

Another one is just as grotesque. A few days ago PBS broadcast the 2000 documentary, From Swastika to Jim Crow—which describes the expulsion of Jewish scholars from Nazi Germany, many of whom ended up in the United States. But they faced heavy anti-Jewish sentiment, anti-German prejudice here as well; most of them were shunned by major universities in northern states. They were hired by Black colleges in southern states, with largely positive outcomes. The Jewish professors could identify with their Black students who faced the brutal reality of segregation. The South lost the Civil War, slavery was ended, but the loathing of Black people did not diminish; if not loathing, then keeping them in their place away from white people. Generations of southern white folks have preserved and nurtured these attitudes, resentful that their way of life—founded on slavery—had been shattered.

And, of course, they could look to the Bible for support. There are no Bible texts at all that prohibit slavery, or call for its abolition. Many serious thinkers have noted that this in one of major flaws of the Ten Commandments, and it would take a long time for ethical sensibilities to evolve to the point of seeing the horrors of slavery. The movement to end slavery gradually gathered strength. Those fighting to end this brutal form of human oppression encountered stiff resistance from those found their world view in the Bible.

Is this the way Christianity is supposed to work?

From Swastika to Jim Crow draws dramatic attention to how “Christian” nations fail to notice the poisonous hatreds they embrace. Love your neighbor and love your enemies have no appeal, no traction at all. The Christian advocates fail to see the dangers of relying on an ancient book that champions a vengeful god. Jesus-script includes mention of punishment by eternal fire, a coming kingdom of god that will see millions of humans killed. One of the constant themes in the apostle Paul’s letter is god’s wrath. This kind of we’ll-get-revenge thinking encourages devout people to take a severe approach toward their perceived enemies. Hence Christians in Germany and the U.S. could justify hatred of Jews, and those in the U.S. could justify hatred of Black people—were lynchings anything other than this? Laws were enacted to keep the races separate, and were enforced ruthlessly. Yes, in, of all places, the Bible Belt. What does that tell us about Bible Values? How can this not be an example of failed Christian theology?

Moreover, it certainly shows the incompetence of the Christian god. How could a powerful, wise, all-knowing god not have noticed—not have foreseen—the consequences of the dreadful Bible verses mentioned above? When this god inspired the author of John’s gospel, surely verse 8:44 would have been erased from John’s brain before he wrote it down. Surely this wise god would have added “you shall not enslave other human beings” to the Big Ten list given to Moses—and have realized that the first two or three on the list were about the divine ego, reflecting this tribal god’s jealousy, and were not all that necessary for human happiness and well-being.

One more thing to be said about the Holocaust. Religious indoctrination can play evil tricks on the human brain. Events that undermine or shatter faith can be ignored and denied, especially episodes of inexplicable suffering and death. Theologians and clergy try their best to explain what obviously seems like god’s indifference or incompetence: he works in mysterious ways, or has a bigger plan that we can’t know about or understand. This is actually an appeal to stop thinking about it, because there are no rational explanations. But still the games go on.

The argument goes that a good god could not possibly have let six million of his people be killed—intentionally murdered—during World War II. Some make this argument to protect their theologies, their conception of god; for some it is an extension of anti-Semitism. Hence we see Holocaust denialism.

Hitler’s anti-Semitism was part of public policy, and his obsession to rid Germany and the world of Jews was clear from the mid-1930s on. The bureaucracy for mass killing was put into place. Hitler hired those who were fiercely committed to this goal. They thought they were doing a great service to the world, hence kept careful records, documenting their accomplishments. Twitter is actually one way to access what we know, through the presence there of Holocaust Education, Auschwitz Memorial, Majdanek Memorial, US Holocaust Museum, Auschwitz Exhibition. The website of the US Holocaust Museum is especially helpful, including its treatment of denialism, here and here. Also, do a Google search for Holocaust memoirs. There are so many of them; those who survived or escaped felt the need to tell their stories of loss, grief, and trauma—and courage. Holocaust deniers would have us believe they’re all liars.

When we closely examine slavery and anti-Semitism, there is simply no way to let Christianity and the New Testament off the hook for these huge sins. In his essay, Hector Avalos argues that “Hitler’s holocaust…is actually the most tragic consequence of a long history of Christian anti-Judaism and racism. Nazism follows principles of killing people for their ethnicity or religion annunciated in the Bible” (p. 369).

And shame on Jesus too—for those who believe that John quoted him correctly. Hector Avalos: “It is in the Gospel of John (8:44) where Jesus himself says that the Jews are liars fathered by the devil. That verse later shows up on Nazi road signs…” (p. 378)

David Madison was a pastor in the Methodist Church for nine years, and has a PhD in Biblical Studies from Boston University. He is the author of two books, Ten Tough Problems in Christian Thought and Belief: a Minister-Turned-Atheist Shows Why You Should Ditch the Faith (2016; 2018 Foreword by John Loftus) and Ten Things Christians Wish Jesus Hadn’t Taught: And Other Reasons to Question His Words (2021). The Spanish translation of this book is also now available.

His YouTube channel is here. He has written for the Debunking Christianity Blog since 2016.

The Cure-for-Christianity Library©, now with more than 500 titles, is here. A brief video explanation of the Library is here.

Is the Gospel of Mark in Papias Our Gospel of Mark?

Here’s the link to this article by Bart Ehrman.

March 4, 2023

Can we trust a source such as Papias on the question of whether our Gospel of Matthew was written by the disciple Matthew and that our Gospel of Mark was written by Mark, the companion of the disciple Peter?

It is interesting that Papias tells a story that is recorded in our Matthew but tells it so completely differently that it appears he doesn’t know Matthew’s version. And so when he says Matthew wrote Matthew, is he referring to *our* Matthew, or to some other book? (Recall, the Gospel he refers to is a collection of Jesus’ sayings in Hebrew; the Gospel of Matthew that *we* have is a narrative, not a collection of sayings, and was written in Greek.) If he *is* referring to our Matthew, why doesn’t he see it as an authoritative account?

Here’s the conflicting story. It involves the death of Judas. And it’s quite a story! Here is my translation of it from my edition, The Apostolic Fathers (Loeb Classical Library, vol. 1; 2004).

But Judas went about in this world as a great model of impiety. He became so bloated in the flesh that he could not pass through a place that was easily wide enough for a wagon – not even his swollen head could fit. They say that his eyelids swelled to such an extent that he could not see the light at all; and a doctor could not see his eyes even with an optical device, so deeply sunken they were in the surrounding flesh. And his genitalia appeared more disgusting and greater than all formlessness, and he bore through them from his whole body flowing pus and worms, and to his shame shame, he emitted pus and worms that flowed through his entire body.

And they say that after he suffered numerous torments and punishments, he died on his own land, and that land has been, until now, desolate and uninhabited because of the stench. Indeed, even to this day no one can pass by the place without holding their nose. This was how great an outpouring he made from his flesh on the ground.” [Apollinaris of Laodicea]

You gotta love it. But, well, what does one make of it? Matthew’s Gospel – the one we have in the New Testament – also describes the death of Judas. But it is not like this at all. According to Matthew, Judas hanged himself (Matt. 27:5). If Papias saw Matthew’s Gospel as an eyewitness authority to the life of Jesus and those around him, why didn’t he accept its version of Judas’s death?

Another alternative is that when Papias describes a Gospel written by Matthew, he isn’t actually referring to the Matthew that we now have. Recall: Papias says two things about the “Matthew” he is familiar with: it consists only of sayings of Jesus and it was composed in Hebrew. Neither is true of our Matthew, which does have sayings of Jesus, but is mainly composed of stories about Jesus. Moreover, it was not composed in Hebrew but in Greek.[1]

It is possible, of course, that like other early Christian scholars, Papias thought Matthew was originally composed in Hebrew when it was not. But it is also possible that these later writers thought Matthew was written in Hebrew because they knew about Papias’s comment and thought he was referring to our Gospel. But he appears not to be: Matthew is not simply a collection of Jesus’ sayings; and in the only place that Papias’s comments overlap with (our) Matthew’s account (the death of Judas), he doesn’t appear to know (our) Matthew.

If Papias was not talking about our Matthew, was he talking about our Mark? As Papias’s quotation about Mark that I cited yesterday indicates, he considered “his” Mark to be problematic because of its disorderly arrangement: that’s why he says that the preaching of Peter was not given “in order.” But that somewhat negative remark in itself is odd, because he doesn’t make the same comment about Matthew, even though the narrative outline of our Matthew is pretty much the same as our Mark – with additional materials added in.

Apart from that, Papias indicates that Mark’s Gospel gives an exhaustive account of everything Peter preached and that it gives it without changing a thing. The reality is that there is no way that anyone could think that the Gospel of Mark in our Bibles today gives a full account of Peter’s knowledge of Jesus. Our Gospel of Mark takes about two hours to read. Are we to think that after spending months (years?) with Jesus, Peter had no more than two hours’ worth of memories?

Of course it may be that Papias is exaggerating for effect. But even so, since he does not appear to be referring to the book we call Matthew, why should we think that he is referring to the book we call Mark? And that, therefore (as Papias indicates) Mark’s Gospel is actually a transcription of Peter’s version of what Jesus said and did?

Despite repeated attempts over the centuries by readers to show that Mark’s Gospel is “Peter’s perspective,” the reality is that if you simply read it without any preconceptions, there is nothing about the book that would make you think, “Oh, this is how Peter saw it all.” Quite the contrary – not only does Peter come off as a bumbling, foot-in-the-mouth, and unfaithful follower of Jesus in Mark (see Mark 8:27-32; 9:5-6; 14:27-31), but there are all sorts of stories – the vast majority – that have nothing to do with Peter or that betray anything like a Petrine voice.

There is, though, a still further and even more compelling reason for doubting that we can trust Papias on the authorship of the Gospels. It is that that we cannot really trust him on much of anything. That may sound harsh, but remember that even the early Christians did not appreciate his work very much and the one comment we have about him personally from an educated church father is that he was remarkably unintelligent.

It is striking that some modern authors want to latch on to Papias for his claims that Matthew and Mark wrote Gospels, assuming, as Bauckham does, that he must be historically accurate, when they completely overlook the other things that Papias says, things that even these authors admit are not and cannot be accurate. If Papias is not reliable about anything else he says, why does anyone think he is reliable about our Gospels of Matthew and Mark? The reason is obvious. It is because readers want him to be accurate about Matthew and Mark, even though they know that otherwise you can’t rely on him for a second.

Does anyone think that Judas really bloated up larger than a house, emitted worms from his genitals, and then burst on his own land, creating a stench that lasted a century? No, not really. But it’s one of the two Gospel traditions that Papias narrates. Here is the only other one. This is the only saying of Jesus that is preserved from the writing of Papias. Papias claims that it comes from those who knew the elders who knew what the disciple John the Son of Zebedee said that Jesus taught:

Thus the elders who saw John, the disciple of the Lord, remembered hearing him say how the Lord used to teach about those times, saying:

The days are coming when vines will come forth, each with ten thousand boughs; and on a single bough will be ten thousand branches. And indeed, on a single branch will be ten thousand shoots and on every shoot ten thousand clusters; and in ever cluster will be ten thousand grapes, and every grape, when pressed, will yield twenty-five measures of wine. And when any of the saints grabs hold of a cluster, another will cry out, ‘I am better, take me, bless the lord through me.” (Eusebius, Church History, 3.39.1)

Really? Jesus taught that? Does anyone really think so? No one I know. Does Papias think Jesus said this? Yes, he absolutely does. Here is what Papias himself says about the traditions of Jesus he records in his five-volume book, in Bauckham’s own translation:

I will not hesitate to set down for you along with my interpretations everything I carefully learned from the elders and carefully remembered, guaranteeing their truth.”

So, can we rest assured about the truth of what Papias says, since he can provide guarantees based on his careful memory? It doesn’t look like it. The only traditions about Jesus we have from his pen are clearly not accurate. Why should we think that what he says about Matthew and Mark are accurate? My hunch is that the only reason readers have done so is because they would like him to be accurate when he says things they agree with, even when they know he is not accurate when he says things they disagree with.

However one evaluates the overall trustworthiness of Papias, in my view he does not provide us with clear evidence that the books that eventually became the first two Gospels of the New Testament were called Matthew and Mark in his time.

[1] That is obvious If Matthew was based in large part on the Gospel of Mark, as is almost everywhere conceded. Matthew agrees with the Greek text of Mark verbatim throughout his account. The only way that would be possible is if he was copying the Greek text into his Greek text.

Who Wrote the Gospels? Our Earliest (Apparent) Reference

Here’s the link to this article written by Bart Ehrman.

March 2, 2023

I have begun to discuss the evidence provided by the early church father Papias that Mark was actually written by Mark. He appears to be the first source to say so. Does he? And if so, is he right?

Here’s how I begin to discuss these matters in my book Jesus Before the Gospels (edited a bit here).

******************************

Papias is often taken as evidence that at least two of the Gospels, Matthew and Mark, were called by those names already several decades after they were in circulation.

Papias was a Christian author who is normally thought to have been writing around 120 or 130 CE. His major work was a five-volume discussion of the teachings of Jesus, called Exposition of the Sayings of the Lord. [1] It is much to be regretted that we no longer have this book. We don’t know exactly why later scribes chose not to copy it, but it is commonly thought that the book was either uninspiring, naïve, or theologically questionable. Later church fathers who talk about Papias and his book are not overly enthusiastic. The “father of church history,” the fourth-century Eusebius of Caesarea, indicates that, in his opinion, Papias was “a man of exceedingly small intelligence” (Church History, 3.39).

Our only access to Papias and his views are in quotations of his book in later church fathers, starting with the important author Irenaeus around 185 CE, and including Eusebius himself. Some of these quotations are fascinating and have been the subject of intense investigation among critical scholars for a very long time. Of relevance to us here is what he says both about the Gospels and about the connection that he claims to have had to eyewitnesses to the life of Jesus.

In one of the most famous passages quoted by Eusebius, Papias indicates that instead of reading about Jesus and his disciples in books, he preferred hearing a “living voice.” He explains that whenever knowledgeable people came to visit his church, he talked with them to ask what they knew. Specifically he spoke with people who had been “companions” of those whom he calls “elders” who had earlier been associates with the disciples of Jesus. And so Papias is not himself an eyewitness to Jesus’ life and does not know eyewitnesses. Writing many years later (as much as a century after Jesus’ death), he indicates that he knew people who knew people who knew people who were with Jesus during his life. So it’s not like having firsthand information, or anything close to it. But it’s extremely interesting and enough to make a scholar sit up and take notice.

Richard Bauckham [In his book Jesus and the Eyewitnesses] is especially enthusiastic about Papias’s testimony, in part because he believes that Papias encountered these people long before he was writing, possibly as early as 80 CE, that is, during the time when the Gospels themselves were being composed [Papias himself, as you can probably guess, says nothing of the sort]. Bauckham does not ask whether Papias’ memory of encounters he had many decades earlier was accurate. But as that is our interest here, it will be important to raise the questions ourselves.

Two passages from Papias are especially important, as Bauckham and others have taken them to be solid evidence that the Gospels were already given their names during the first century. At first glance, one can see why they might think so. Papias mentions Gospels written both by Mark and by Matthew. His comments deserve to be quoted here in full. First on a Gospel written by Mark.:

This is what the elder used to say, “when Mark was the interpreter [Or: translator] of Peter he wrote down accurately everything that he recalled of the Lord’s words and deeds – but not in order. For he neither heard the Lord nor accompanied him; but later, as I indicated, he accompanied Peter, who used to adapt his teachings for the needs at hand, not arranging, as it were, an orderly composition of the Lord’s sayings. And so Mark did nothing wrong by writing some of the matters as he remembered them. For he was intent on just one purpose: not to leave out anything that he heard or to include any falsehood among them.” (Eusebius, Church History, 3. 39)

Thus, according to Papias, someone named Mark was Peter’s interpreter or translator (from Aramaic?) and he wrote down what Peter had to say about Jesus’ words and deeds. He did not, however, produce an orderly composition. Still, he did record everything he ever heard Peter say and he did so with scrupulous accuracy. We will see that these claims are highly problematic, but first consider what Papias says also about a Gospel by Matthew:

And so Matthew composed the sayings in the Hebrew tongue, and each one interpreted [Or: translated] them to the best of his ability. (Eusebius, Church History, 3. 39)

There are numerous reasons for questioning whether these passages – as quoted by Eusebius — provide us solid evidence that the New Testament Gospels were given their names in the late first or early second century.

First, it is somewhat curious and certainly interesting that Eusebius chose not to include any quotations from Papias about Luke or John. Why would that be? Were Papias’s views about these two books not significant? Were they unusual? Were they contrary to Eusebius’s own views? We’ll never know.

Second, it is important to stress that in none of the surviving quotations of Papias does he actually quote either Matthew or Mark. That is to say, he does not give a teaching of Jesus, or a summary of something he did, and then indicate that he found it in one of these Gospels. That is unfortunate, because it means that we have no way of knowing for certain that when he refers to a Gospel written by Mark he has in mind the Gospel that we now today call the Gospel of Mark. In fact there are reasons for doubting it, as I will show in my next post.

[1] See the Introduction and the collection of all the fragments of Papias that I give in The Apostolic Fathers, vol. 2 pp. 85-118.

Did Mark Write Mark? What the Apostolic Fathers Say

Here’s the link to this article written by Bart Ehrman.

March 1, 2023

Did Mark write Mark? A couple of weeks ago I did an eight-lecture course on the Gospel of Mark for my separate (unrelated to the blog) venture, a series of courses on “How Historians Read the Bible” (the courses are available on my website: www.bartehrman.com). It was a blast. One of the things I loved about doing it was that I was able to read and reread scholarship on Mark and I learned some things I had long wondered about, and re-learned other things that I used to know.

One of the things I had to think seriously about for the first time in some years was the question of why church fathers in the second century (but when?) began claiming that our second Gospel was written by John Mark, allegedly a secretary for the apostle Peter. That took me straight back to the question of the reliability of an early Christian writer named Papias (writing around 120 or 130 CE?).

Papias gets used all the time as proof that Mark wrote Mark. Conservative Christian scholars cite him on the point as “gospel truth.” But for the past 30 years I’ve found the evidence unconvincing. I’ve written about the issue briefly on the blog before, but I decided to look up my lengthiest discussion of the matter in my book Jesus Before the Gospels (HarperOne, 2016) and lo and behold, I made some points there that I didn’t remember!

I thought it would be worthwhile to present that discussion here. It tries to show why Papias’ witness is so problematic for establishing the authorship of both Mark and Matthew, the only two Gospels he mentions in the snippets of his writings we still have. This will take three posts.

In this one I give the backdrop to the testimony of Papias.

******************************

The Gospel writers are all anonymous. None of them gives us any concrete information about their identity. So when did they come to be known as Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John? We might begin by considering the earliest references to the books, which occur in a group of authors who were writing, for the most part, immediately after the New Testament period. These are the so-called “Apostolic Fathers.” That term is not meant to indicate that these authors themselves were apostles, but that, in scholarly opinion starting hundreds of years ago (though no longer), they were companions of the apostles. Theirs are among our earliest non-canonical writings.[1]

In the various Apostolic Fathers there are numerous quotations of the Gospels of the New Testament, especially Matthew and Luke. What is striking about these quotations is that in none of them does any of these authors ascribe a name to the books they are quoting. Isn’t that a bit odd? If they wanted to assign “authority” to the quotation, why wouldn’t they indicate who wrote it?

Almost certainly the first apostolic father is the book of 1 Clement, a letter from the church of Rome to the church of Corinth written around 95 CE (and so, before some of the last books of the New Testament) and traditionally claimed to have been composed by the third bishop of Rome, Clement. Scholars today widely reject that claim, but for our purposes here it does not much matter. Just to give an example of how the Gospels are generally treated in the Apostolic Fathers, I quote one passage from 1 Clement:

We should especially remember the words the Lord Jesus spoke when teaching about gentleness and patience. For he said: “Show mercy, that you may be shown mercy; forgive, that it may be forgiven you. As you do, so it will be done to you; as you give, so it will be given to you; as you judge, so you will be judged; as you show kindness, so will kindness be shown to you; the amount you dispense will be the amount you receive.” (1 Clement 13:1-2)

This is an interesting passage, and fairly typical, because it conflates a number of passages from the Gospels, containing lines from Matthew 5:7; 6:14-15; 7:1-2, 12; Luke 6:31, and 36-38. But the author does not name the Gospels he has taken the texts from, and certainly doesn’t attribute them to eyewitnesses. Instead, he simply indicates that this is something that Jesus said.

The same is true of other Apostolic Fathers. In chapter one of the intriguing book known as the Didache, which contains a set of ethical and practical instructions to the Christian churches, the anonymous writer quotes from Mark 12, Matthew 5 and 7; and Luke 8. But he never names these Gospels. Later he cites the Lord’s prayer, virtually as it is found in Matthew 6; again he does not indicate his source.

So too, as a third example, Ignatius of Antioch clearly knows Matthew’s story of the star of Bethlehem (Ignatius, Ephesians 19) and Matthew’s story of Jesus’ baptism which was undergone “in order to fulfill all righteousness” (Smyrneans 1). But he doesn’t mention that the account was written by Matthew. Similarly, Polycarp of Smyrna quotes Matthew chapters 5, 7, and 26 and Luke 6, but he never names a Gospel.

This is true of all of our references to the Gospels prior to the end of the second century. The Gospels are known, read, and cited as authorities. But they are never named or associated with an eyewitness to the life of Jesus. There is one possible exception: the fragmentary references to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark in the writings of the church father, Papias.

[1] For a translation of their writings, with introductions, see Bart D. Ehrman, The Apostolic Fathers, 2 vols. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2003). I have used this translation for all my quotations.

Did a God Creat this Universe?

Life inside the Bible Bubble: If you’re saved, God is your Daddy

Watch this clip where the preacher makes claims about reality–that the Christian God is your Daddy (if you’ve been ‘saved’) and you can talk to him just like you do your earthly father.

https://screencast-o-matic.com/watch/c0eV2IVyKsc

After watching this clip, please think. Does sky-daddy treat you like your earth-daddy? The answer is an unequivocal no. Of course, this assumes your earthly father is a caring, loving father (most are, naturally, although admittedly, some are horrible bastards).

My point is, a normal earthly father will give his life for his son or daughter. He will do anything for his child. If he sees her about to walk out into a busy street, he will rush to stop her. If the father see’s his son about to drink poison from under the sink, he will come to the rescue. Why will the earthly father do these things? Because he loves his children.

One would think the Christian God, the one who is supposedly omniscient, omnipotent, and omni-benevolent would be at least as loving and kind as a normal earthly father.

But, is he? I think not.

Think about the real world vs. the imaginary world as you listen to “Sam Harris vs. Religion” in this YouTube video.

After pondering Sam’s shocking truths, ask yourself, where was God when young children recently froze to death in Afghanistan?

I encourage you to read: Dying Children and Frozen Flocks in Afghanistan’s Bitter Winter of Crisis. Here’s the link (note, you may have to sign-in, or set-up a free account, or subscribe).

How would you rate sky-daddy’s love for his children? Is your response, “these weren’t his children because they had never been ‘saved’?”

I thought God loves all children?

Luke 18:16-17 KJV

But Jesus called them unto him, and said, Suffer little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of God. Verily I say unto you, Whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child shall in no wise enter therein.

And, what about the song, “Jesus Loves the Little Children of the World”?

Here’s the lyrics:

Jesus loves the little children

All the children of the world

Red and yellow, black and white

They are precious in His sight

Jesus loves the little children of the world

Jesus died for all the children

All the children of the world

Red and yellow, black and white

They are precious in His sight

Jesus died for all the children of the world

Jesus loves the little children

All the children of the world

Red and yellow, black and white

They are precious in His sight

Jesus loves the little children of the world

Jesus loves the little children of the world

Think back, did you catch it from Sam’s video? “Nine million children die every year before they reach the age of five.” Many, if not most of their parents, are praying to the Christian God as their child suffers and dies.

Could it be sky-daddy doesn’t love his ‘children’ like a normal earthy-father?

Or, could it be sky-daddy (aka, the Christian God) is simply imaginary?

I sincerely believe that if you will ‘read-to-death’ you will, sooner or later, come to realize the answer is the latter.

Teachings of Jesus that Christians Dislike and Ignore, Number 2

By David Madison 2/24/23.

Here’s the link to this article.

They just say NO to their Lord and Savior

Weird scripture has given rise to weird versions of Christianity. In Mark 16 the resurrected Jesus assures those who believe that they will be able to “pick up snakes”—as well as drink poison, heal people by touch, speak in tongues, and cast out demons (Mark 16:17-18). So there are indeed Christian sects today that make a big deal of handling snakes, and on occasion we read that a snake-handling preacher has died. These folks didn’t get the word that this text is found in the fake ending of Mark—that is, verses 16:9-20 are not found in the oldest manuscripts of the gospel; these were added later by an unknown crank. Most Christians today, we can assume, do not rank these among their favorite Bible verses.

Indeed there are many verses that the devout pretend aren’t there, because these verses have a strong cult flavor. I’m sure that the community of the faithful today are shocked to hear their religion called a cult—they wince at this designation. But they don’t pick up on this fact because they are unaware of so many embarrassing verses, especially in Jesus-script in the gospels. Unaware is one way to put it, obtuse is also appropriate. Or they’re just careless, in the sense of not taking care to read the gospels. If they took seriously the claim that the gospels are the word of their god, why don’t they binge-read these basic four documents, to discover as much detail as possible about their lord and savior?

The clergy are thankful they don’t. Their parishioners might soon appreciate why the word cult works pretty well in describing early Christianity. New Testament scholars noticed this a long time ago. But most church folks are unaware of their writings, and are happy to worship Jesus as presented to them by the church, since they were toddlers.

One of the signs of cult fanaticism is the demand for absolute loyalty. Another is weird belief about how a god is going to intervene in human history. One manifestation of this at the time of Jesus was messianism: belief that god would send a mighty holy hero who would put things right. For believers in first century Palestine, this included throwing out the Romans, and this would be a cataclysmic event with widespread death and suffering. The early Jesus cult embraced this idea, savoring the idea that their god would get even. This idea of vengeance—and the demand for absolute devotion to the cult—ended up in Jesus-script. It doesn’t fit at all with carefully nurtured Sunday School image of Jesus that so many of the devout adore today.

It is quite common for Christians today to give high ratings to family values. They are confident that Jesus placed high value on family love and loyalty—hence his severe condemnation of divorce. But in Matthew’s 10th chapter we find Jesus counseling his disciples on the problems they’ll face as a consequence of following him. However, this reads more like a warning—written by Matthew well after Jesus had died—to those who belonged to the Jesus cult. Nonetheless this is presented as Jesus-script, often printed in red as a guarantee that these are authentic words of Jesus:

“Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth; I have not come to bring peace but a sword.For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law,and one’s foes will be members of one’s own household” (Matthew 10:34-36). In Mark 13:12-13 we find a similar warning: “Sibling will betray sibling to death and a father his child, and children will rise against parents and have them put to death,and you will be hated by all because of my name. But the one who endures to the end will be saved.”

The next couple of verses derail even more into cult fanaticism, i.e., the holy leader expects a supreme level of devotion: “Whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me, and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me, and whoever does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me” (Matthew 10:37-38).

If the author of Luke’s gospel was aware of this Jesus-script, he clearly wasn’t happy with it. He wanted the meaning to be bluntly clear: “Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple” (Luke 14:26). Luke felt that the word hate would make the point better, i.e., that the cult expected undivided loyalty. Not only hatred of family was required, but even of life itself.

Why isn’t this verse a deal breaker? If you’ve been taught for years to adore Jesus, but then discover this verse (and even the milder one in Matthew), why not head for the exit? Is this the holy hero you really want? The most common response to this text I’ve heard is, “Oh, Jesus couldn’t have meant that!” This is based on the idealized image of Jesus firmly lodged in pious brains. But the Greek word for hate is right there? How do these excuse-makers know—some 2,000 years after the fact—what Jesus was thinking? What’s the data to back up this claim? Isn’t Luke supposed to be reliable reporter—according to Christian theology? He quoted Jesus using the word hate.

It’s not hard to spot the maneuvering used by church authorities to disguise the plain meaning of the text. In the Revised Standard Version, the editors chose this heading for Luke 14:25-33: The Cost of Discipleship. Most of the devout probably assume that following Jesus makes demands on their lives, so this heading gives no offense. But an honest heading would have been, The Cult Fanaticism Displayed by Jesus. We could put it bluntly to churchgoers: do you indeed love Jesus so much that you hate your family? To keep people in the dark, some modern translations simple remove the word hate. The Message Bible’s version of Luke 14:26: “Anyone who comes to me but refuses to let go of father, mother, spouse, children, brothers, sisters—yes, even one’s own self!—can’t be my disciple.”

Does “let go” of family members and even life itself render this text more acceptable? Even more contemptable: this is not a translation. This is a paraphrase to disguise the meaning of Luke’s Jesus-script. Plainly stated: this “translator” is lying; he doesn’t want readers to know what’s in the Bible. When cult fanaticism is so obvious, cover it up.

What’s the reason for not heading for the exit? There can be major consequences for leaving the church, for saying out loud that you no longer believe. This is alarming for those who still embrace Jesus, and they often shun those who have made the brave decision. Or they declare that eternal punishment in fire is the reward for disbelief: “Whoever believes in the Son has eternal life; whoever disobeys the Son will not see life but must endure God’s wrath” (John 3:36). “The one who believes and is baptized will be saved, but the one who does not believe will be condemned” (Mark 16:16).

Even before Matthew and Luke had created their strident Jesus script about “loving Jesus more than family” and “hating family to be a disciple,” Mark presented a story of Jesus identifying true believers as his real family:

“Then his mother and his brothers came, and standing outside they sent to him and called him. A crowd was sitting around him, and they said to him, ‘Your mother and your brothers are outside asking for you.’ And he replied, ‘Who are my mother and my brothers?’And looking at those who sat around him, he said, ‘Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does the will of God is my brother and sister and mother.’” (Mark 3:31-35).

The Revised Standard Version editors calls this section: The True Kindred of Jesus, endorsing Jesus slighting his family.

Whoever does the will of God. Cult leaders are always confident that they know what their god wants, and they attract loyal followers who take their word for it. This cult mentality prevails today among Christians who know for sure that their god hates abortion, gay marriage, and separation of church and state. They are eager to gain power and enforce their cult fanaticism, while being blind to their own faults. I’m baffled that the Catholic Church gets away with what it does. It might qualify as the most dangerous cult in the world for this major sin: maintaining a priesthood infiltrated with men who rape children. And coverup seems to be a primary response.

Here is another example of Luke going beyond Matthew in cult fanaticism. In Matthew 8:19-22, we read:

“A scribe then approached [Jesus] and said, ‘Teacher, I will follow you wherever you go.’ And Jesus said to him, ‘Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.’ Another of his disciples said to him, ‘Lord, first let me go and bury my father.’ But Jesus said to him, ‘Follow me, and let the dead bury their own dead.’”

Luke added this, 9:60-62:

“And Jesus said to him, ‘Let the dead bury their own dead, but as for you, go and proclaim the kingdom of God.’ Another said, ‘I will follow you, Lord, but let me first say farewell to those at my home.’And Jesus said to him, ‘No one who puts a hand to the plow and looks back is fit for the kingdom of God.’”

The cult hero is obsessed with his understanding of the kingdom of god, in this case: if you want to say goodbye to your family, you’re not fit for the kingdom. How is this not cult fanaticism? We have to assume that most churchgoers just aren’t paying close attention. How do they really feel about this? Jesus doesn’t want to hear that a potential follower has an obligation to bury his father; that another wants to say goodbye to his family before descending into servile obedience to a religious zealot who wanders the land with “nowhere to lay his head.” If the devout bothered to read/study the gospels carefully—which in this case means examining the Matthew and Luke texts side by side—they might notice that something is wrong here. This is not attractive theology, designed to win followers who aren’t on the verge of insanity.

And speaking of insanity, here’s one of my favorite gospel quotes, Mark 3:20-21:

“Then he went home, and the crowd came together again, so that they could not even eat. When his family heard it, they went out to restrain him, for people were saying, ‘He has gone out of his mind.’”

This is not found in the other gospels. We indeed wonder what the author of Mark could have meant by “out of his mind”—Mark who portrayed Jesus as an exorcist. Which is hardly surprising: the ancient world embraced all manner of superstitions. Mark, by the way, knew nothing of the extravagant birth narratives found in Luke and Matthew. When the shepherds visited the manger to see the newborn Jesus, and reported the message of the singing angels (that this Jesus was a savior, the messiah), “… Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart” (Luke 2:19). Wouldn’t she—and the family—have expected out-of-the-ordinary behavior when Jesus set out to proclaim his message?

When we take a close look at all the Jesus-script in the gospels, there is so much that is disappointing—and even alarming, when it reflects apocalyptic delusions. In preparing my 2021 book, Ten Things Christians Wish Jesus Hadn’t Taught, my list of not-so great—even bad—Jesus sayings came to 292.

In this article I’ve focused on a few verses that reflect the extremism of the gospel authors. Article Number 1 in this series is here.

David Madison was a pastor in the Methodist Church for nine years, and has a PhD in Biblical Studies from Boston University. He is the author of two books, Ten Tough Problems in Christian Thought and Belief: a Minister-Turned-Atheist Shows Why You Should Ditch the Faith (2016; 2018 Foreword by John Loftus) and Ten Things Christians Wish Jesus Hadn’t Taught: And Other Reasons to Question His Words (2021). The Spanish translation of this book is also now available.

His YouTube channel is here. He has written for the Debunking Christianity Blog since 2016.

The Cure-for-Christianity Library©, now with more than 500 titles, is here. A brief video explanation of the Library is here.

Do We Suffer Because We Have “Free Will”?

Here’s the link to this article written by Bart Ehrman on February 26, 2023.

In my previous posts I discussed a class I once taught at Rutgers University on how the various biblical authors deal with the problem of suffering – the problem of how there can be such horrible suffering in a world that is said to be controlled by an all-loving and all-powerful God (who therefore wants the best for people and is able to provide it). Many of my students, as I pointed out, think that there’s an easy answer: we suffer because of “free will.” If we weren’t free to love and hate, to do good and do harm, we would just be robots or computers, not humans. If God wanted to create humans, as opposed to machines, necessarily we have to be free to hurt others. And many people do so, often in horrendous ways.

Does that solve the problem? Naturally we dealt with that issue in my class. Here is how I discussed those conversations in my book on suffering, God’s Problem: How The Bible Fails to Answer our Most Important Question – Why We Suffer (Oxford University Press, 2008).

*******************************

It was, in fact, fairly easy to show my students some of the problems with this standard modern explanation that suffering comes from free will. Yes, you can explain the political machinations of the competing political forces in Ethiopia (or in Nazi Germany or in Stalin’s Soviet Union or in the ancient worlds of Israel and Mesopotamia) by claiming that humans had badly handled the freedom given to them. But how can you explain drought? When it hits, it is not because someone chose not to make it rain. Or how do you explain hurricanes that destroy New Orleans? Or tsunamis that kill hundreds of thousands overnight? Or earthquakes, or mudslides, or malaria, or dysentery? And so on.

Moreover, the claim that free will stands behind all suffering has always been a bit problematic, at least from a thinking perspective. Most people who believe in God-given free will also believe in an afterlife. Presumably people in the afterlife will still have free will (they won’t be robots then either, will they?). And yet there won’t be suffering (allegedly) then. Why will people know how to exercise free will in heaven if they can’t know how to exercise it on earth?

In fact, if God gave people free will as a great gift, why didn’t he give them the intelligence they need to exercise it so that we could all live happily and peaceably together? You can’t argue that he wasn’t able to do so, if you want to argue he was all powerful. Moreover, if God sometimes intervenes in history in order to counteract the free will decisions of others — for example, when he destroyed the Egyptian armies at the Exodus (they freely had decided to oppress the Israelites) or when he fed the multitudes in the wilderness in the days of Jesus (people who had chosen to go off to hear him without packing a lunch), or when he counteracted the wicked decision of the Roman governor Pilate to destroy Jesus by raising the crucified Jesus from the dead — if he intervenes sometimes to counteract free will, why does he not do so more of the time? Or indeed, all of the time.

At the end of the day, one would have to say that the answer is a mystery. We don’t know why free will works so well in heaven but not on earth. We don’t know why God doesn’t provide the intelligence we need to exercise free will. We don’t know why he sometimes contravenes the free exercise of the will and sometimes not. But the problem is that if in the end the question is resolved by saying it is a mystery, then we no longer have an answer. We are admitting there is no answer. The solution of free will, in the end, ultimately leads to the conclusion that we can’t understand, even though we imagine we are giving an answer.

As it turns out, that is one of the common answers asserted by the Bible. We just don’t know why there is suffering. But other answers in the Bible are just as common — in fact, even more common. In my class at Rutgers I wanted to explore all these answers, to see what the Biblical authors thought about such matters, and to evaluate what they had to say.

Based on my experience with the class, I decided at the end of the term that I wanted to write a book about it, a study of suffering and biblical responses to it. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that I wasn’t ready to write the book. I was just 30 years old at the time, and although I had seen a lot of the world, I recognized that I had not seen nearly enough of it. A book like this requires years of thought and reflection, and a broader sense of the world and fuller understanding of life.

I’m now twenty years older [OK, with this blog post thirty-five years older!], and I still may not be ready to write the book. It’s true, I’ve seen a lot more of the world over these years. I’ve experienced a lot more pain myself, and have seen the pain and misery of others, sometimes close up: broken marriages, failed health, cancer taking away loved ones in the prime of life, suicide, birth defects, children killed in car accidents, homelessness, mental disease — you can make your own list of your past twenty years. And I’ve read a lot: genocides and ethnic cleansings not only in Nazi Germany but also in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia, and now Darfur; terrorist attacks, massive starvation, epidemics ancient and modern, mudslides that kill 30,000 Columbians in one fell swoop, droughts, earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis.

Still, even with twenty years of additional experience and reflection, I may not be ready to write the book. But I suppose in another twenty years, with the horrible suffering in store for this world, I may still feel the same way. So I’ve decided to write it now.

Seeing the Problem of Suffering as a PROBLEM

Here’s the link to this article written by Bart Erhman on February 23, 2023. Click here to read the first article in this series.

In my previous post I began to talk about how thinkers in the Jewish and Christian traditions have wrestled with the problem of suffering. I indicated that the technical term for this “problem” is “theodicy,” and it is often said to involve the status of three assertions which all are typically thought to be true by those in these two religions, but if true appear to contradict one another. The assertions are these:

God is all-powerful.

God is all-loving.

There is suffering.

How can all three be true at once? If God is all powerful, then he is able to do whatever he wants (and can therefore remove suffering). If he is all loving, then he obviously wants the best for people (and therefore does not want them to suffer). And yet people suffer. How can that be explained? As I pointed out some thinkers have tried to deny one or the other of the assertions: either God is not actually all powerful, or he is not all loving, or there is no suffering.

But as I explain in the introduction to my book God’s Problem (Oxford Press, 2008) …

******************************

Most people who wrestle with the problem want to say that all three assertions are true, but that there is some kind of extenuating circumstance that can explain it all. For example, in the classical view of the prophets of the Hebrew Bible, as we will see at length in the next couple of chapters, God is certainly all powerful and all loving; one of the reasons there is suffering is because his people have violated his law or gone against his will, and he is bringing suffering upon them in order to force them to return to him and lead righteous lives.

This kind of explanation works well so long as it is the wicked who are the ones who suffer. But what about the wicked who prosper while the ones who try to do what is right before God are wracked with interminable pain and unbearable misery? How does one explain the suffering of the righteous? For that other explanations need to be used (for example, that it will all be made right in the afterlife – a view not found in the prophets but in other biblical authors) (there are, as I’m suggesting, other explanations as well in the Bible and in popular thinking).

Even though a scholar of the Enlightenment – Leibniz – came up with the term “theodicy,” and even though the deep philosophical problem has been with us only since the Enlightenment, the basic “problem” has been around since time immemorial. This was recognized by the intellectuals of the Enlightenment themselves. One of them, the English philosopher David Hume, pointed out that the problem was stated some twenty-five hundred years ago by one of the great philosophers of ancient Greece, Epicurus:

Epicurus’s old questions are yet unanswered:

Is God willing to prevent evil but not able? Then he is impotent.

Is he able but not willing? Then he is malevolent.

Is he both able and willing? Whence, then, evil?[i]

As I was teaching my course on biblical views of suffering at Rutgers, over twenty years ago (well… thirty-five now!!), I began to realize that the students seemed remarkably, and somewhat inexplicably, detached from the problem. It was a good group of students: smart and attentive. But they were for the most part white, middle-class kids who had not experienced a lot of pain in their lives yet, and I had to do some work in order to help them realize that the problem of suffering was in fact a problem.

This was the time of one of the major Ethiopian famines. In order to drive home for my students just how disturbing suffering could be, I spent some time with them dealing with the problem of the famine. It was an enormous problem. In part because of the political situation, but even more because of a massive drought, there were eight million Ethiopians who were confronted with severe shortages and who, as a result, were starving. Every day there were pictures in the papers of poor souls, famished, desperate, with no relief in sight. Eventually one out of every eight died the horrific death of starvation.

That’s some two million people, starved to death, in a world that has far more than enough food to feed all its inhabitants, a world where American farmers are paid to destroy their crops, a world where most of us in this country ingest far more calories than our bodies need or want. To make my point, I would show pictures of the famine to the students, pictures of emaciated Ethiopian women with famished children on their breasts, desperately sucking to get nourishment that would never come, both mother and children eventually destroyed by the ravages of hunger.

Before the semester was over, I think my students got the point. Most of them did learn to grapple with the problem. When the course had started, many of them had thought that whatever problem there was with suffering could be fairly easily solved.

The most popular solution they had was one that I would judge most people in our (Western) world today still hold on to. It has to do with free will. According to this view, the reason there is so much suffering in the world is that God has given humans free will. Without the free will to love and obey God, we would simply be robots doing what we were programed to do. But since we have the free will to love and obey, we also have the free will to hate and disobey, and this is where suffering comes from. Hitler, the Holocaust, Idi Amin, corrupt governments throughout the world, corrupt humans inside government and outside of it – all of these are explained on the grounds of free will.

As it turns out, this was more or less the answer given by some of the great intellectuals of the Enlightenment, including Leibniz, who argued that humans have to be free in order for this world to be the best world that could come into existence. For Leibniz, God is all powerful and so was able to create any kind of world he wanted; and since he was all loving he obviously wanted to create the best of all possible worlds. This world – with freedom of choice given to its creatures – is therefore the best of all possible worlds.

Other philosophers rejected this view – none so famously, vitriolically, and even hilariously as the French philosopher Voltaire, whose classic novel Candide tells the story of a man (Candide) who experiences such senseless and random suffering and misery, in this allegedly “best of all worlds,” that he abandons his Leibnizian upbringing and adopts a more sensible view, that we can’t know the whys and wherefores of what happens in this world, but should simply do our very best to enjoy it while we can.[ii] Candide is still a novel very much worth reading – witty, clever, and damning. If this is the best world possible – just imagine what a worse one would be.

******************************

I will continue my reflections on the matter starting at this point, in the next post.

[i]. David Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (the sentiments are those expressed by his fictitious caracter named Philo). Xxx?

[ii]. Voltaire. Candide: or Optimism. Tr. Theo Cuffe (New York: Penguin, 2005).