Category: Reality

The Marginalian: John Gardner on the Key to Self-Renewal Across Life and the Art of Making Rather Than Finding Meaning

Here’s the link to this article.

BY MARIA POPOVA

A person is not a potted plant of predetermined personality but a garden abloom with the consequences of chance and choice that have made them who they are, resting upon an immense seed vault of dormant potentialities. At any given moment, any seed can sprout — whether by conscious cultivation or the tectonic tilling of some great upheaval or the composting of old habits and patterns of behavior that fertilize a new way of being. Nothing saves us from the tragedy of ossifying more surely than a devotion to regularly turning over the soil of personhood so that new expressions of the soul can come abloom.

In the final years of his long life, former U.S. Secretary of Heath, Education, and Welfare John Gardner (October 8, 1912–February 16, 2002) expanded upon his masterwork on self-renewal in the posthumously published Living, Leading, and the American Dream (public library), examining the deepest questions and commitments of how we become — and go on becoming — ourselves as our lives unfold, transient and tender with longing for meaning.

With an eye to the mystery of why some people and not others manage to live with vitality until the end, and to the fact that life metes out its cruelties and its mercies with an uneven hand, Gardner writes:

One must be compassionate in assessing the reasons. Perhaps life just presented them with tougher problems than they could solve. It happens. Perhaps they were pulled down by the hidden resentments and grievances that grow in adult life, sometimes so luxuriantly that, like tangled vines, they immobilize the victim. Perhaps something inflicted a major wound on their confidence or their self-esteem. You’ve known such people — feeling secretly defeated, maybe somewhat sour and cynical, or perhaps just vaguely dispirited. Or perhaps they grew so comfortable that adventures no longer beckoned.

Recognizing that the challenges we face are both personal and structural, that we are products of our conditions and conditioning but also entirely responsible for ourselves, he adds:

We build our own prisons and serve as our own jailkeepers… but clearly our parents and the society at large have a hand in building our prisons. They create roles for us — and self-images — that hold us captive for a long time. The individual intent on self-renewal will have to deal with ghosts of the past — the memory of earlier failures, the remnants of childhood dramas and rebellions, the accumulated grievances and resentments that have long outlived their cause. Sometimes people cling to the ghosts with something almost approaching pleasure — but the hampering effect on growth is inescapable.

Of the lessons we learn along the vector of living — things difficult to grasp early in life — he considers the hardest yet most liberating:

You come to understand that most people are neither for you nor against you, they are thinking about themselves. You learn that no matter how hard you try to please, some people in this world are not going to love you, a lesson that is at first troubling and then really quite relaxing.

But no learning is harder, or more countercultural amid this cult of achievement and actualization we live in, than the realization that there is no final and permanent triumph to life. A generation after the poet Robert Penn Warren admonished against the notion of finding yourself and a generation before the psychologist Daniel Gilbert observed that “human beings are works in progress that mistakenly think they’re finished,” Gardner writes:

Life is an endless unfolding, and if we wish it to be, an endless process of self-discovery, an endless and unpredictable dialogue between our own potentialities and the life situations in which we find ourselves. The purpose is to grow and develop in the dimensions that distinguish humankind at its best.

In a sentiment that mirrors the driving principle of nature itself, responsible for the evolution and survival of every living thing on Earth, he considers the key to that growth:

The potentialities you develop to the full come as the result of an interplay between you and life’s challenges — and the challenges keep coming, and they keep changing. Emergencies sometimes lead people to perform remarkable and heroic tasks that they wouldn’t have guessed they were capable of. Life pulls things out of you. At least occasionally, expose yourself to unaccustomed challenges.

The supreme reward of putting yourself in novel situations that draw out dormant potentialities is the exhilaration of feeling new to yourself, which transforms life from something tending toward an end into something cascading forward in a succession of beginnings — for, as the poet and philosopher John O’Donohue observed in his magnificent spell against stagnation, “our very life here depends directly on continuous acts of beginning.” This in turn transforms the notion of meaning — life’s ultimate aim — from a product to be acquired into a process to be honored.

Gardner recounts hearing from a man whose twenty-year-old daughter was killed in a car crash. In her wallet, the grief-stricken father had discovered a printed passage from a commencement address Gardner had delivered shortly before her death — a fragment evocative of Nietzsche’s insistence that “no one can build you the bridge on which you, and only you, must cross the river of life.” It read:

Meaning is not something you stumble across, like the answer to a riddle or the prize in a treasure hunt. Meaning is something you build into your life. You build it out of your own past, out of your affections and loyalties, out of the experience of humankind as it is passed on to you, out of your own talent and understanding, out of the things you believe in, out of the things and people you love, out of the values for which you are willing to sacrifice something. The ingredients are there. You are the only one who can put them together into that unique pattern that will be your life.

Complement with the pioneering education reformer and publisher Elizabeth Peabody on middle age and the art of self-renewal, the great nonagenarian cellist Pablo Casals on the secret to creative vitality throughout life, and this Jungian field guide to transformation in midlife, then revisit Nick Cave on blooming into the fulness of your potentialities and Simone de Beauvoir on the art of growing older.

No One You Love Is Ever Dead: Hemingway on the Most Devastating of Losses and the Meaning of Life

Here’s the link to this article.

BY MARIA POPOVA

Along the spectrum of losses, from the door keys to the love of one’s life, none is more unimaginable, more incomprehensible in its unnatural violation of being and time, than a parent’s loss of a child.

Ernest Hemingway (July 21, 1899–July 2, 1961) was in his twenties and living in France when he befriend Gerald and Sara Murphy. The couple eventually returned to America when one of their sons fell ill, but it was their other son, Baoth, who died after a savage struggle with meningitis.

Upon receiving the news, the thirty-five-year-old writer sent his friends an extraordinary letter, part consolation for and part consecration of a loss for which there is no salve, found in Shaun Usher’s moving compilation Letters of Note: Grief (public library).

On March 19, 1935, Hemingway writes:

Dear Sara and Dear Gerald:

You know there is nothing we can ever say or write… Yesterday I tried to write you and I couldn’t.

It is not as bad for Baoth because he had a fine time, always, and he has only done something now that we all must do. He has just gotten it over with…

About him having to die so young — Remember that he had a very fine time and having it a thousand times makes it no better. And he is spared from learning what sort of a place the world is.

It is your loss: more than it is his, so it is something that you can, legitimately, be brave about. But I can’t be brave about it and in all my heart I am sick for you both.

Absolutely truly and coldly in the head, though, I know that anyone who dies young after a happy childhood, and no one ever made a happier childhood than you made for your children, has won a great victory. We all have to look forward to death by defeat, our bodies gone, our world destroyed; but it is the same dying we must do, while he has gotten it all over with, his world all intact and the death only by accident.

In a breathtaking sentiment evocative of Anaïs Nin’s admonition against the stupor of near-living, and of poet Meghan O’Rourke’s grief-honed conviction that “the people we most love do become a physical part of us, ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are created,” Hemingway adds:

Very few people ever really are alive and those that are never die; no matter if they are gone. No one you love is ever dead.

With this, echoing Auden’s insistence that “we must love one another or die,” he comes the closest he ever came to formulating the meaning of life. Like David Foster Wallace, who addressed the meaning of life with such exquisite lucidity shortly before he was slain by depression, Hemingway too would lose hold of that meaning in the throes of the agony that would take his life a quarter century later. Now, from the fortunate platform of the prime of life, he writes:

We must live it, now, a day at a time and be very careful not to hurt each other. It seems as though we were all on a boat together, a good boat still, that we have made but that we know will never reach port. There will be all kinds of weather, good and bad, and especially because we know now that there will be no landfall we must keep the boat up very well and be very good to each other. We are fortunate we have good people on the boat.

Complement with the young Dostoyevsky’s exultation about the meaning of life shortly after his death sentence was repealed, Emily Dickinson on love and loss, Thoreau on living through loss, and Nick Cave — who lived, twice, the unimaginable tragedy of the Murphys — on grief as a portal to aliveness, then revisit the fascinating neuroscience of your brain on grief and your heart on healing.

The Marginalian: On Giving Up: Adam Phillips on Knowing What You Want, the Art of Self-Revision, and the Courage to Change Your Mind

Here’s the link to this article.

BY MARIA POPOVA

“A self that goes on changing is a self that goes on living,” Virginia Woolf wrote. Nothing is more vital to the capacity for change than the uncomfortable luxury of changing your mind — that stubborn refusal to ossify, the courageous willingness to outgrow your views, anneal your values, and keep clarifying your priorities. It is incredibly difficult to achieve because the very notion of the self hinges on our sense psychological continuity and internal consistency; because we live in a culture whose myths of heroism and martyrdom valorize completion at any cost, a culture that contractually binds the present self to the future self in mortgages and marital vows, presuming unchanging desires, forgetting that who we are is shaped by what we want and what we want goes on changing as we go on growing.

Changing — your mind, your life — is also painfully difficult because it is a form of renunciation, a special case of those necessary losses that sculpt our lives; it requires giving something up — a way of seeing, a way of being — in order for something new to come abloom along the vector of the “endless unfolding” that is a life fully lived, something that leaves your new emerging self more fully met.

The psychoanalyst Adam Phillips offers a salve for that perennial difficulty in On Giving Up (public library) — an exploration and celebration of giving up as “a prelude, a precondition for something else to happen, a form of anticipation, a kind of courage,” “an attempt to make a different future” that “get us the life we want, or don’t know that we want.”

He considers how countercultural such reframing is:

We tend to value, and even idealize, the idea of seeing things through, of finishing things rather than abandoning them. Giving up has to be justified in a way that completion does not; giving up doesn’t usually make us proud of ourselves; it is a falling short of our preferred selves… Giving up, in other words, is usually thought of as a failure rather than a way of succeeding at something else. It is worth wondering to whom we believe we have to justify ourselves when we are giving up, or when we are determinedly not giving up.

At the heart of the book is the recognition that renunciation is the fulcrum of change. We give things up, Phillips observes, “when we believe we can no longer go on as we are.” (For many, this is the central crisis of midlife.) It is a kind of sacrifice in the service of a larger, better life — but this presumes knowledge of the life we want, and it is often experiences we didn’t know we wanted that end up magnifying our lives in the profoundest ways. (Nothing illustrates this better than The Vampire Problem.)

Phillips considers the paradox:

The whole notion of sacrifice depends upon our knowing what we want… Giving up, or giving up on, anything or anyone always exposes what it is we take it we want… To give something up is to seek one’s own assumed advantage, one’s apparently preferred pleasure, but in an economy that we mostly can’t comprehend, or, like all economies, predict… We calculate, in so far as we can, the effect of our sacrifice, the future we want from it… to get through to ourselves: to get through to the life we want.

“I did not know that I could only get the most out of life by giving myself up to it,” the psychiatrist and artist Marion Milner wrote a century ago in her clarifying field guide to knowing what you really want — which is, in the end, the hardest thing in life, for our self-knowledge is cratered with blind spots, clouded by conditioning, and perennially incomplete. Phillips — who draws on Milner’s magnificent book, as well as on Kafka and Judith Butler, Henry and William James, Hamlet and Paradise Lost — observes that, in this regard, giving up is a kind of “gift-giving.” He writes:

Not being able to give up is not to be able to allow for loss, for vulnerability; not to be able to allow for the passing of time, and the revisions it brings.

And what would life be without continual acts of self-revision?

It is our ego-ideals — the stories we tell ourselves and the world about who we are and who we ought to be, fantasies of coherence and continuity mooring us to a static idealized self — that feed what Phillips calls the “tyranny of completion.” But human beings are rough drafts that continually mistake themselves for the final story, then gasp as the plot changes on the page of living. We do this largely because we are captives of comfort in our habits of thought and feeling, victims of certainty — that supreme narrowing of the mind — when it comes to our own desires. That we don’t fully know what we want because we are half-opaque to ourselves, that something we didn’t think we wanted may end up enlarging our lives in unimaginable ways, is a kind of uncertainty that unravels us. But if we can bear the frustration of the figuring, we may live into a larger and more authentic life.

Building upon his excellent earlier writing on why frustration is necessary for satisfaction in love, Phillips writes:

Our frustration is the key to our desire; to want something or someone is to feel their absence; so to register or recognize a lack would seem to be the precondition for any kind of pleasure or satisfaction. Indeed, in this account, frustration, a sense of lack, is the necessary precondition for any kind of satisfaction.

[…]

The traditional story about lack and desire describes a closed system; in this story I can never be surprised by what I want, because somewhere in myself I already know what is missing; my frustration is the form my recognition takes, it is a form of remembering.

Wanting is recovery, not discovery… There is a part of oneself that needs to know what it is doing, and a part of oneself that needs not to… a part of oneself that needs to know what one wants and a part of oneself that needs not to.

It is in the continual investigation of our desires, with all the frustration of our polyphonous parts, that we find the recovery and gift-giving which giving up can bring — a way of giving our lives back to ourselves and giving ourselves forward to our lives. Phillips distills the central predicament:

The question is always: what are we going to have to sacrifice in order to develop, in order to get to the next stage of our lives?

Couple On Giving Up with John O’Donohue on beginnings, Allen Wheelis on how people change, and Judith Viorst on the life-shaping art of letting go, then revisit Phillips on why we fall in love, breaking free from the tyranny of self-criticism, and the relationship between “fertile solitude” and self-esteem.

Losing My Religion, by Michael Bigelow

Here’s the link to this article.

From Elder in the Jehovah’s Witnesses religion to proponent of scientific naturalism, by Michael Bigelow

In several of my books I have recounted my own journey from born-again Christian to religious skeptic, in the context of understanding how beliefs are formed and change (in The Believing Brain), how religious and faith-based beliefs differ (or at least should differ) from scientific and empirical beliefs (in Why Darwin Matters), and the relationship of science and religion: same-worlds model, separate-worlds model, conflicting-worlds model (in Why People Believe Weird Things). As a result, over the years I have received a considerable amount of correspondence from Christians who want to convince me to come back to the faith, along with one-time believers who recount their own pathway to non-belief. At my urging after emails revealing autobiographical fragments of his own loss of faith, in this edition of Skeptic guest contributor Michael Bigelow narrates his sojourn from Elder in the Jehovah’s Witnesses religion to proponent of scientific naturalism. As he recalls in this revealing passage from the essay below:

A literal interpretation of the Bible proved incorrect. Humans were not created in 4026 BC, nor was the earth engulfed by a flood 4,400 years ago. I was wrong. My personal discovery categorically rendered the Bible’s account of natural history as false. This revelation cast doubt on the entirety of the Bible.

—Michael Shermer

Losing My Religion

In 2008, I faced one of the most uncomfortable moments of my life. For Jehovah’s Witnesses, the memorial of Jesus’ death is the most significant event of the year. It is a solemn occasion in which a respected Elder addresses a packed Kingdom Hall, filled with believers and visitors. That year, I delivered the talk and managed the ritual passing of the wine and unleavened bread. Many attendees praised me afterward, claiming it was clear that God’s spirit was upon me. However, for nearly four years before that evening, I had ceased praying and believing and was deeply troubled by the hypocrisy of teaching things I could no longer accept as true.

An even more distressing day occurred in 2012 when I publicly renounced my ties with Jehovah’s Witnesses. A former friend described my departure as a “nuclear blast” that devastated the three congregations I had once served. My decision to leave based on conscience resulted in immediate and complete shunning by all my former friends, my family, and even my two adult sons.

Turning Points

I was born into a large extended family of Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1961 in San Diego, California. Our family of eight led a life typical for Witness households: we didn’t celebrate holidays, birthdays, or participate in patriotic events and after-school activities. My entire social circle was within the religious community, and our Saturdays were dedicated to door-to-door preaching. This lifestyle felt completely normal to me as a child.

During the 1960s, Jehovah’s Witnesses were taught that Armageddon was imminent and strongly suggested this would occur in 1975. We believed that on this day, God would destroy all who were not part of our faith, creating a deep sense of urgency to save not just ourselves but others. Driven by this belief, my father moved our family from the comfort of Southern California to frugal living in Northern New England, aiming to reach an underserved community with our teachings.

In New Hampshire, at our new Kingdom Hall, I met a young lady who would become my wife. At just twelve years old, we were both deeply committed to our faith, known among Jehovah’s Witnesses as “The Truth,” and we knew we would eventually wed. Despite our parents’ efforts to keep us apart, it seemed inevitable that we would be together. After graduating high school, we married young, securing minimum wage jobs and making ends meet with second-hand furniture and tight budgets.

I progressed through various positions of responsibility, both in our congregation and at the manufacturing company where I worked. Together, we raised and homeschooled our two sons, continually striving to live up to the commitments of our dedication to God.

In 1991, I was appointed as an Elder in our local congregation, a role laden with significant responsibilities. My duties included teaching at congregation meetings, providing guidance to those struggling, leading preaching efforts, and speaking at large conventions. Following in my father’s footsteps, I established a reputation as a dedicated minister. Despite my commitment, I harbored private doubts. Natural disasters and biblical accounts like the Noachian flood, which seemed improbable, troubled me. I was also disturbed by the notion of God allowing Satan to corrupt His perfect creation. We were taught to manage such doubts through prayer and meditation, a strategy that sufficed until innovations like Google Earth introduced new perspectives that challenged my views further.

Deconversions

Accounts of shunning, deconversion, and abandoning supernatural beliefs are increasingly common today. While my story isn’t unique in its occurrence, it is distinct in its unfolding. Many are leaving Jehovah’s Witnesses due to the organization’s strict control, unfulfilled prophecies, evolving doctrines, prohibition of blood transfusions, biased translations of the Bible, and mishandling of child sexual abuse cases.

These are valid reasons to leave, but my departure was driven by something else. When I realized the biblical narrative of natural history couldn’t possibly be true, my entire belief system collapsed. Yet, I continued to serve as a teacher, shepherd, and public figure in the organization for five more years, knowing I was an atheist. This period was a personal torment for which I still feel remorse. Looking back, I can’t see how I could have chosen differently. Here is how it all unfolded.

I have always had a profound love for the outdoors, and spending time in the mountains has been a significant part of my life. In the late 1960s, my grandparents took my brothers and me on a road trip from San Diego to the Sierra Nevada mountains in Central California. The majestic, snow-capped and rugged terrain captivated my imagination. This experience left a lasting impression, and by the mid 1980s I began organizing annual backpacking and climbing trips to the Sierras. Each spring, I would meticulously plan these trips from New Hampshire, pouring over maps, guidebooks, and equipment lists.

By the early-1990s, the Palisade range of the Sierra had become my personal sanctuary, notable for the ranges’ largest active glacier. The first time I observed the glacier from an elevated viewpoint, I noticed it was shrinking. At the glacier’s base lay a horseshoe-shaped moraine nearly a hundred feet high. Below the moraine’s rim, a glacial pond of milky, silty water formed, scattered with broken granite and ice. This observation troubled me; something significant was amiss, yet it remained just beyond my understanding.

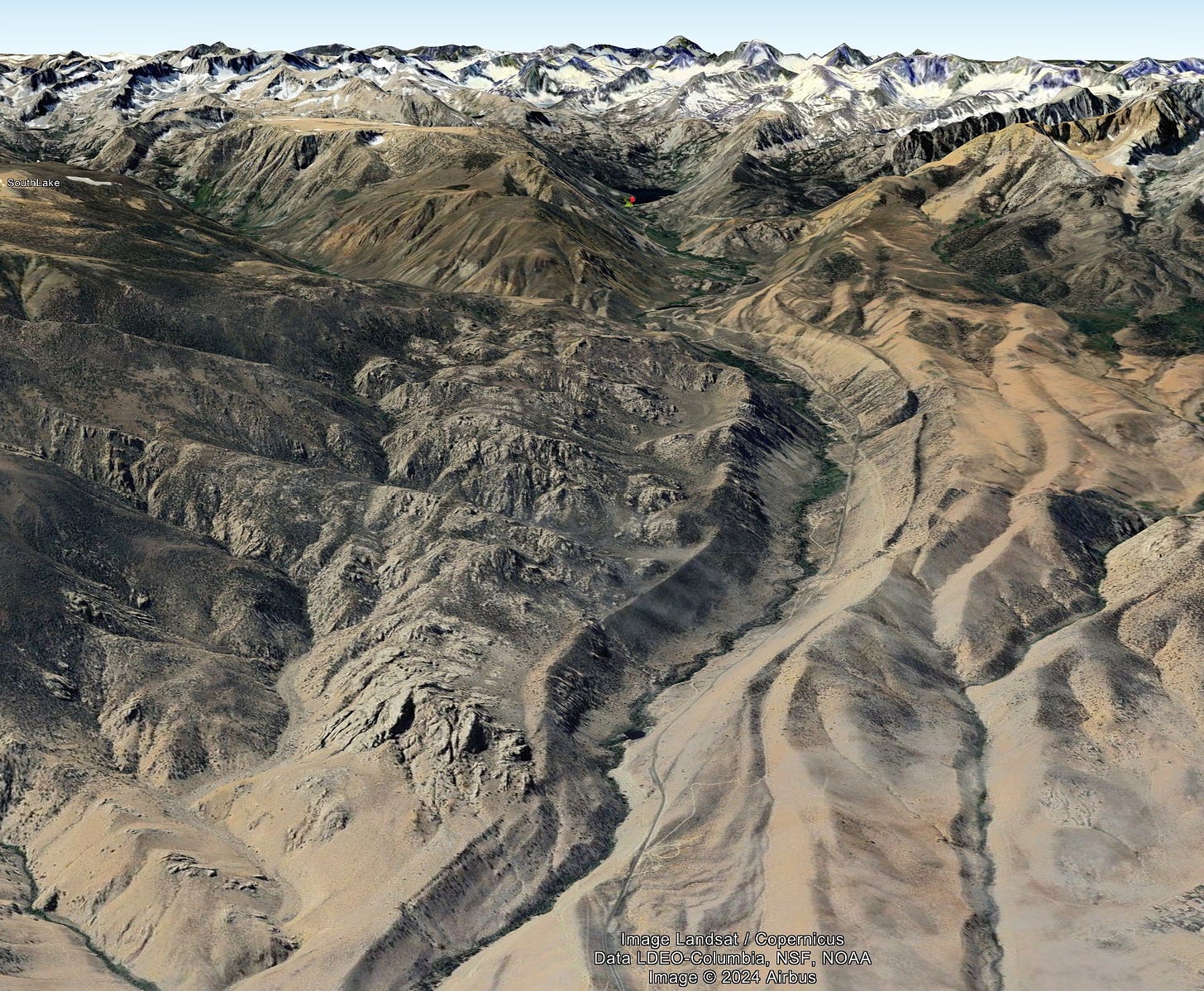

Palisade Glacier. Photo by the author.

From the perspective of day-age, fundamentalist Christians, it is believed that the entire planet was submerged underwater 4,400 years ago during Noah’s flood. Thus, every existing landform—whether a canyon, glacier, desert, cavern, or mountain—either existed under water at that time or formed naturally afterward. I didn’t contemplate these ideas when I first saw that glacier or when I climbed the 14,000-foot mountains surrounding it. Yet, a seed of new doubt was planted.

By the late 1990s, I had a new tool for planning my trips to the Sierra: Google Earth. This technology allowed me to view satellite imagery of the entire mountain range. I could meticulously plan climbing routes, select camping spots, and observe glaciers—not only those that were still active but, more intriguingly, those that had vanished. The disappearance of glaciers suggested ice ages, a concept that I was not ready to accept as it contradicts Jehovah’s Witnesses’ teachings, which deny such geological periods.

Business Interlude and Deep Questioning of the Faith

In 1999, the company I had been with since my teenage years offered me a job in Asia. At that time, I was managing two of their operations in New England. They had recently acquired a company in Taiwan and wanted me to oversee their manufacturing in China. My wife and I deliberated over this opportunity, with our primary concern being the ability to maintain our spiritual commitments and contribute to a local congregation in Taiwan. After reaching out to the headquarters of our religious organization, we learned there was an English-speaking group in the city we would be moving to, and they welcomed our participation. Encouraged by this, we decided to relocate.

Upon moving to Taiwan, I soon realized the necessity of learning Mandarin Chinese to succeed in my role. Motivated by this challenge, I dedicated myself to studying with an intensity I had never shown before. In high school, my focus had been on my future wife rather than academics, making me a lackluster student. However, in Taiwan, I quickly learned Mandarin and developed effective study habits that significantly changed my life’s direction. This deep dive into the language not only helped in my immediate job but also enabled me and my business partners to eventually acquire the Asian company, securing our financial future. Additionally, working in locations away from my family provided me with the private space and time to deeply research and reflect on significant topics, further enriching my understanding and perspectives.

In the early 2000s, while living in Asia, I continued planning trips to the Sierra Nevada. By then, Google Earth’s satellite imagery had greatly improved, allowing me to see individual boulders and trees. This tool became indispensable for both planning excursions and simply enjoying the landscapes from afar. Around 2003, a particular land feature near Bishop, California, caught my attention and profoundly shifted my perspective. There, a small river emerges from the high country and runs through a wide, empty glacial moraine into the arid Owens Valley (see Google Earth image below). The moraine, a pristine trench once filled by a glacier, is starkly visible, stretching nearly to the desert floor. This observation challenged my previous beliefs: it seemed highly unlikely that this landform was ever submerged underwater or formed shortly after a flood. As I reviewed images from all the earth’s great mountain ranges, I found similar features. This realization opened a floodgate of curiosity and skepticism about the traditional narratives I had accepted.

Religious Dogma vs. Carbon Dating

The first research book I purchased was Glaciers of California: Modern Glaciers, Ice Age Glaciers, the Origin of Yosemite Valley, and a Glacier Tour in the Sierra Nevada by Bill Guyton. This book ignited a thirst for knowledge that grew exponentially. Studying glaciers led me to explore broader geology, which in turn introduced me to plate tectonics and scientific dating methods. These concepts opened the door to pre-history and the works of scholars like Jared Diamond, Steven Mithen, and many others. As I delved deeper, consuming books, downloading scientific papers, and visiting field sites, I was desperately seeking any evidence to affirm the Bible’s accounts of natural history. Internally, I struggled with my faith-based commitment that “I can’t be wrong,” but the mounting evidence made me fear that I was losing the argument against established scientific consensus.

As I delved into pre-history, I frequently encountered carbon dating—a method I had been taught to distrust. From the 1960s until the early 1990s, Jehovah’s Witnesses employed pseudo-scientific arguments to discredit the reliability of carbon dating. Reflecting on these apologetics with a better understanding of logical fallacies and flawed reasoning, I now recognize those arguments as circular, appealing to authority, and rooted in motivated reasoning. Despite my resistance, the evidence supporting carbon dating seemed overwhelming. In my quest to align my beliefs with factual accuracy, I had to personally validate carbon dating’s efficacy. I came across a statement from Carl Sagan, who said, “When you make the finding yourself—even if you’re the last person on Earth to see the light—you’ll never forget it.” This sentiment resonated with me deeply; I had to experience this realization firsthand. Sagan was right—I will never forget the moment I accepted the truth of carbon dating.

During the early 2000s, part of my research turned to the peopling of the Americas, a captivating area of paleontology that held particular significance for me at the time. According to 17th-century biblical chronologist James Ussher, humans were created from dirt in 4004 BC, specifically on October 22. Jehovah’s Witnesses adopt a similar timeline, placing human creation at 4026 BC. Arriving at Ussher’s date involves recording and counting forward or backward from known events based on the ages of biblical kings and patriarchs. This chronology is accepted as accurate by many biblical literalists. However, if evidence showed that the Americas were populated thousands of years before these dates, it would profoundly challenge this timeline and compel me to reconsider my beliefs further.

As I delved into the peopling of the Americas, I discovered that the ash and pumice layer from the eruption of Mt. Mazama (now Crater Lake) serves as a precise stratigraphic marker. At Paisly Cave and Fort Rock Cave, archaeologists found human artifacts both within and beneath the Mt. Mazama volcanic tephra layer. These artifacts included campfire remains, hand-woven sagebrush sandals, grinding stones, projectile points, basketry, cordage, human hair, and the butchered remains of now-extinct animals, such as camelids and equids. Many of these artifacts were carbon dated, with results ranging from 9,100 to 14,280 years before present (BP). Therein lies a hurdle—those pesky carbon dating references. I struggled to reconcile these dates with my previous beliefs, as they suggested human presence in the Americas long before the biblical timeline of human creation.

The abundant artifacts found within and beneath the debris from Mt. Mazama prompted researchers to pinpoint the eruption’s date more accurately. In 1983, Charles Bacon estimated the eruption occurred around 6,845 years +/-50 (BP) using the beta counting method of carbon dating on burned wood samples found in Mazama’s lava flows. A more refined date was published in 1996 by D.J. Hallet, who dated the eruption to approximately 6,730 BP, with a margin of error of +/- 40 years. This estimate utilized the more advanced Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) carbon dating technique on burned leaves and twigs mixed with Mazama tephra in nearby lakebed sediments. Despite the improved methodology, my skepticism persisted because it still relied on carbon dating, a technique I was still reluctant to trust fully.

The quest for a more accurate date of the Mt. Mazama eruption led to significant advancements in 1999 when C.M. Zdanowicz and his team published a paper with a revised eruption date. They leveraged the precise nature of annual layers in Greenland Ice Cores, hypothesizing that they could pinpoint a near absolute year for the eruption by identifying Mazama’s volcanic signatures within the ice. Starting with calibrated carbon dates from previous research as a baseline, they sampled layers above and below the target area, searching for traces of Mazama.

The team found volcanic glass and other chemical markers consistent with those found near the eruption site. Zdanowicz published a date range of 7,545 to 7,711 years before present, aligning closely with previous carbon dating results. This discovery was a profound moment of humility and awakening for me; the precision of carbon dating not only pinpointed the location of Mazama tephra in the Greenland ice core but also demonstrated the reliability of this dating method. It confirmed what many scientists had long understood: carbon dating is a powerful tool for establishing historical timelines, and these were in direct conflict with my religious beliefs.

The End of the End

A literal interpretation of the Bible proved incorrect. Humans were not created in 4026 BC, nor was the earth engulfed by a flood 4,400 years ago. I was wrong. My personal discovery categorically rendered the Bible’s account of natural history as false. This revelation cast doubt on the entirety of the Bible. When biblical authors wrote of a literal flood and Adam and Eve as the first humans, they were unaware of their inaccuracies. This prompted me to investigate the origins of the Old Testament. I concluded that this collection of books was crafted to forge a grand narrative, one that provided the people of Israel with a national identity and a distinguished status before God as His chosen people, dating back to the creation of the first humans.

If there was a definitive End of Faith date for me, it would be December 26, 2004. Witnessing the catastrophic effects of the Sumatra earthquake and tsunamis, and having experienced another earlier and massive earthquake in Taiwan firsthand, I was deeply shaken. During a period when I was already grappling with new and challenging information, I saw our volatile planet claim hundreds of thousands of lives. This led me to a stark realization: “This is God’s planet. Either He caused this, or He allowed it to happen.” Just days after the disaster, I considered a third, more profound possibility: God does not exist. He didn’t cause the disaster nor did He allow it; He simply isn’t there. With this realization, my constant wondering, doubting, and blaming ceased. The peace I found in accepting this personal truth is indescribable.

Despite realizing that truth, fear of the unknown future and the potential devastation to my loved ones and their trust in me as a teacher and shepherd kept me living a lie. For many more years, I endured the heavy burden of this deceit, which led to terrifying, public panic attacks, some of which occurred before large audiences. This period was marked by intense internal conflict as I struggled to reconcile my public persona with my private understanding. Although it took years, I eventually had to leave the religion.

The Aftermath

Rejecting the Bible, which had been the cornerstone of my faith, propelled me toward scientific skepticism. Like many before me, I was drawn to the writings of Michael Shermer and works featured in Skeptic magazine. My departure from biblical teachings spurred me to explore questions about belief, the brain, and supernatural claims. The insights of thinkers like Carl Sagan, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, Bertrand Russell, Guy P. Harrison, Robert Green Ingersoll, and Thomas Paine solidified my embrace of scientific naturalism. Their eloquent articulations reinforced and expanded upon the truths I had come to recognize on my own.

But what of my life now? What about my former hope of living forever on a paradisiacal earth? What of my loved ones and my marriage? I have witnessed many who have left their faith struggle to cope with the reality that this life is all there is. Our purpose is what we decide to make it. No one has, or likely ever will, live forever. The concept of a religious afterlife is a comforting illusion, a fortified barrier constructed to shield us from the fear of death.

I’ve discovered that I’ve become a better person as a non-believer than I ever was as a believer. There’s a kind of grotesque self-assuredness that comes from believing you have the only true answers to the universe’s most important questions. Such certainty naturally breeds a tendency toward dogmatism in all aspects of life. Regrettably, some of this dogmatic attitude lingered even after I abandoned my faith. Initially, I felt compelled to make my immediate family—especially my wife—understand what I had learned. This approach was unwise and unkind. I have since moved past that phase. My wife and sons are aware of my beliefs and my rejection of what I consider falsehoods. I desire their happiness within their faith as Jehovah’s Witnesses, striving to be the best people they can be. This is particularly important for my wife, who deeply needs and cherishes her beliefs. I know of no other couple who have managed to survive and thrive under similar circumstances, and I am committed to not letting go of that.

Since renouncing my supernatural beliefs, I’ve grown more tolerant of others’ faiths, though I still cannot condone the terrible acts or political agendas that sometimes arise from religious doctrines. However, I remain acutely aware that many people on this “pale blue dot” rely deeply on the hope and peace their faith provides. As long as these beliefs do not result in harm, I see them as fundamentally benign. This perspective allows for a respectful coexistence in our diverse world.

As for what the future holds, I cannot say. If someone had described my current life to me 25 years ago, I would have been incredulous. Yet here I am, leading a life full of wonder and satisfaction. I intend to make the most of each day until the very end—when the sun goes dark on my last day, so will I.

Southern Baptist leaders release new analysis of their decline

Here’s the link to this article.

We don’t get treats like this very often. Savor it.

by CAPTAIN CASSIDY FEB 01, 2024

by CAPTAIN CASSIDY FEB 01, 2024

Overview:

This analysis contains some information we don’t usually see out of the Southern Baptist Convention, including an egregious example of goalpost-shifting to avoid dealing with the metric most indicative of decline.

Reading Time: 8 MINUTES

For years now, Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) members have watched their denomination decline in both cultural dominance and memberships. Recently, the branch of the denomination devoted to information gathering and analysis, Lifeway Research, released some new information about that decline.

In short, that decline’s nowhere near over yet.

How Southern Baptists use the Annual Church Profile—and how they don’t

The Annual Church Profile (ACP) is a yearly survey of Southern Baptist churches. It asks them a variety of questions about:

- Baptisms

- Total membership

- Attendance in-person (and online, since the pandemic)

- Sunday School and small group enrollment and attendance (a small group is something like a Sunday School class for adults; members pray together, study the Bible, and have Jesusy discussions)

- How much money the church has given to SBC projects

The SBC operates as a kind of mother ship to dozens of state-level conventions. Most American states have one. Some states have so few Southern Baptists that they must combine with other states, while others are so large they have more than one. But generally, each state has its own state convention. Churches operate more or less independently, as do the state conventions representing them. Each state-level convention runs its own ACP.

Note two major facts about the ACP.

First, some state-level conventions sometimes ask questions in a different way than others. Or they may leave out some questions entirely.

Second, it’s completely voluntary. Southern Baptist leaders do not require participation in it. So a church may elect to answer all questions, or just some, or only one, or none at all. Participation has no effect on membership in the denomination.

For the ACP discussed here today, 69% of Southern Baptist churches participated by answering at least one question on the survey.

Sidebar: Now consider why a Southern Baptist church might not participate

Given what we know of the SBC as a whole and about Southern Baptists in particular, we can make some educated guesses about churches that refused to participate in the ACP.

I’m betting that the 31% of churches that didn’t participate weren’t exactly doing great, metrics-wise. If they’d been baptizing people left and right, running stunningly effective evangelism programs, and growing so fast their pastors’ sermons were standing-room-only, no way no how would they forget to tell the mother ship about it, or simply refuse to participate.

It’d be extremely interesting to see what Southern Baptist stats would look like if the denomination’s leaders required ACP participation. But I don’t think it’ll ever happen. When such two-edged proposals come up, Southern Baptist leaders begin sweating greasy droplets of muh autonomous local church.

(That’s also why Southern Baptist leaders in the Old Guard faction don’t want to do anything about the denomination’s sex abuse crisis. They’re just so incredibly concerned, you see, about muh autonomous local church. But of course, when those autonomous local churches decide to be inclusive toward gay people or hire women to be pastors, suddenly even the Old Guard faction finds its teeth; archive.)

What Southern Baptist analysts found in the 2022 ACP

You can find a summary of the 2022 ACP here. It looks like the state-level conventions are still gathering the information together from 2023 to send to the mother ship for last year. On the site for the California Southern Baptist Convention (archive), I found a due date for the 2023 ACP: March 1, 2024. So we’re a ways off from knowing how the denomination did last year.

Usually, though, Southern Baptist leaders release a little tickle in the early spring. They like to do that in the run-up to their big Annual Meeting every summer. So keep an eye out for it around April. For now, we’ve got 2022 to keep us company.

And oh, what company it is!

Overall, this new analysis paints a picture of deep decline that is nowhere near even bottoming-out yet. In almost every single way imaginable, Southern Baptist congregations are in trouble. The pandemic only accelerated their decline.

This is probably one of the most dire graphs I have ever seen out of the SBC:

That can’t have been easy for some poor Southern Baptist graphic artist to make. But it’s truthful. After their disastrous pandemic drop in 2020, Southern Baptist churches rebounded all the way to 180,177 baptisms. And even that’s awful. They haven’t seen that small of a number since around 1920, when churches dunked 173,595 people.

(Info about specific years’ performance comes from Annual Reports on the official SBC site. The reports contain info about the previous year. So the 2023 Annual Report contains info about 2022, and so on and so forth. If I give a date like 2018 for a figure, it can be found in the next year’s report, so in this case 2019.)

This is Southern Baptist info we don’t normally get

Years ago, I ran across a report released around 2014 by the Pastors’ Task Force on SBC Evangelistic Impact & Declining Baptisms. It’s an analysis of the 2012 ACP. It is an absolutely eye-opening document, too. I highly recommend it to anyone interested in evangelical-watching.

And I recommend it for one important reason:

It reveals that Southern Baptist leaders have access to a wealth of information about baptisms that they don’t generally make available to the public. One of the most important metrics they reveal is the age of the people getting baptized. I’ve never seen this exact information provided anywhere else.

In the 2012 ACP report, as the Task Force revealed, 25% of Southern Baptist churches had zero baptisms. 60% of respondents didn’t baptize anyone between 12-17, while 80% reported “0-1 young adult baptisms (age 18-29 bracket).” Worse, the Task Force revealed this damning bit of trivia: “The only consistently growing age group in baptisms is age five and under.”

This new analysis of the 2022 ACP makes a good chaser for it, because it, too, reveals a lot of information that doesn’t usually appear anywhere else. For instance, it mentions that about 43% of Southern Baptist churches had no baptisms at all in 2022, while 34% had 1-5. That’s a lot more coming up empty than did in 2012.

Of note, in 2012, churches baptized about 315k people and counted 15.8M members. In 2022, they recorded 180,177 baptisms and 13.2M members.

I’m extremely interested in knowing how the ages broke out in those 2022 stats. If the mother ship had that info in 2012-2014, then it does now.

And they’re not talkin’, which makes me strongly suspect that most of the reported baptisms are the under-18 children of existing adult members and returning members who want to make a public demonstration of their re-affiliation.

(Related: You must be born again and again and again; Gaming a broken system with baptisms.)

And stuff most people could probably guess about Southern Baptist churches generally

As one might guess, Southern churches saw more baptisms, as did urban churches and new churches (less than 20 years old). Rural areas have a lot fewer potential new recruits living nearby, and well, Southern Baptist churches always did do well in the American South. It’s in the name!

New churches, as well, saw a lot more baptisms than old ones did. A church established more than a century ago is probably pretty stuck in its ways and traditional. It’s had time to attract and then alienate all the people in the area. But a lot of evangelicals’ ears perk up when they notice a brand-new church in their vicinity. They think it’ll be different than the ones they’ve tried. They’re willing to visit and check it out.

Churchless believers, those Christians who believe but have left church culture and membership behind, seem particularly open to trying brand-new churches. Often, they’ve been burned hard by other churches, but many say they want to find a good church to join.

Alas, new Southern Baptist churches often have trouble surviving past about five years. The people they attract might leave, taking their wallets with them, or the church’s leaders might turn out not to know how to lead volunteer groups very well.

As a May 2023 article hints (article), the mother ship’s general strategy for about 15 years now has been to scattershot new churches everywhere imaginable in the frantic hopes that they outweigh the number of churches closing each year. Every one of those struggling churches needs a pastor, even if that pastor will also need a day job.

“I’m glad I’m retired,” said one former Southern Baptist pastor in 2022 (archive) of the entire situation with pastors’ overall short tenure.

Selling Southern Baptist church membership on the basis of real-world social benefits

I’ve noticed lately that Southern Baptists have been talking up the real-world social benefits of joining their churches. That’s a wise strategy, far better than the one they’ve been using:

- Convince marks that the Bible is literally true and Jesus is literally a real god who does real stuff in the real world (and will send the disobedient to Hell)

- Then, sell marks active, engaged SBC church membership as the only way to Jesus correctly

Pushing harder on real-world benefits will generate a lot more interest, as long as they can deliver on their promises.

And so we see in the 2022 ACP analysis that churches with very active, engaged members also tend to bag the most baptisms. The more people participate in small groups, in particular, the generally higher their baptism rate—but churches that claimed 100% participation tended to have way fewer baptisms on average (5.9) than those claiming 75-99% participation (7.2).

What’s really interesting about that figure is that churches claiming 25-49% participation got 6.4, and those claiming 0-24% participation got 5.5. So that 100% participation figure of 5.9 baptisms is definitely a strange one.

Also, very large churches with 500+ attending weekly worship services tended to be the only ones that increased their number of baptisms between 2017 (5.2) and 2022 (5.6). Most regions were doing well just to maintain their 2017 numbers.

The Southern Baptist baptism ratio still blows chunks

The number that Southern Baptist leaders consider their very most important is what they call their baptism ratio. That’s the ratio of baptized people per existing Southern Baptist members. It asks: How many Southern Baptists’ resources did it take to get one person baptized?

And it’s why Southern Baptist leaders have known about their decline for about 50 years. That number speaks to the effectiveness of Southern Baptist recruiting and retention. Until about 1974, their ratio hovered in the 1:20-1:29 range. They liked it there. But after 1974, it never dipped that low again.

(Note: The SBC’s Conservative Resurgence began in earnest in the 1970s. This takeover by ultraconservative schemers and hypocrites finally ended in the late 1990s with solid victory.)

In 1985, the baptism ratio hit 1:41 at last. Despite Southern Baptist churches doing everything they could think of to fight it back down into the 1:30s again, it hit 1:50 in 2012. I saw a lot of Southern Baptist panicking around that time. It didn’t do any good then, either, because in 2018, it reached 1:60. I heard nothing about it that time, though.

Then, the pandemic blasted that already-struggling baptism ratio to smithereens:

- 2019: 1:62

- 2020: 1:114

- 2021: 1:88

As of 2022, they’d clawed their way back up to 1:73.

Which leads to the most hilarious bit of Southern Baptist goalpost-shifting I’ve ever seen

That is just shockingly bad, by Southern Baptist standards. That gets evangelicals to wondering if maybe Jesus just doesn’t like the denomination or something.

So the analysts behind the 2022 ACP report have figured out a way to move the goalposts!

Now they’re going to give a ratio between baptisms per every 100 people attending worship services. And doing it that way, they get a baptism ratio of 1:20 for 2022!

However, that’s still a decline, as they tell us themselves:

Another way to examine baptisms and rates for churches is by considering the number per worship attendees. Unfortunately for Southern Baptists, that number is also in decline. With worship attendance also falling, that means baptisms are falling at a faster rate than attendance. [. . .]

Among Southern Baptist churches that reported attendance in 2022, for every 100 people attending a worship service in a Southern Baptist church, five people were baptized on average. In other words, it took 20 Southern Baptists to reach one person. While that is the best number in the past four years, it’s still a decline from 2017 (5.9 per 100) and part of an overall negative trend.2022 ACP Analysis, Lifeway Research

Man alive, I really and truly don’t know how Southern Baptist leaders are going to deal with this in the next few years. Sooner or later, someone’s going to remember that the Conservative Resurgence was supposed to fix the decline. That’s how its architects and leaders sold it to the flocks. But it seems to have done the exact opposite.

Worse, pushing hard on the supposed real-world social benefits of joining Southern Baptist churches won’t work unless the people in those churches live up to the hype. And most of them just don’t, which we know because they’re falling apart across the board.

That simple truth may explain the relative success of the largest churches in the denomination: Plenty of stuff to do, plus a much higher chance of finding someone nice to make friends with. But if there’s another group that offers those same benefits for less hassle, watch out!

To grow, Baptists need to up their affability game in ways they have never had to do for their entire existence as a denomination. I just don’t think they’re up for the challenge. And I strongly suspect their leaders would agree with me there.

New map captures explosive rise of the nonreligious

Here’s the link to this article.

by ADAM LEE JAN 26, 2024

by ADAM LEE JAN 26, 2024

Overview:

The rapid, unprecedented growth of the “nones” continues apace. The nonreligious are now larger than any single religious group in America, and they’ve become the majority in several states.

Reading Time: 4 MINUTES

Beyond the tumult of elections and the noise of the news cycle, there are bigger trends that will shape the future of our world. One of these trends is the growth of the “nones”—the Americans who identify as atheist, agnostic, or who just don’t belong to any religion.

Decades ago, the nones were a tiny minority. But in the early 21st century, their numbers started growing. And that growth was rapid: less like a gentle ramp, more like a rocket blasting off.

In a little under two decades, the nones rose from insignificance to national prominence. They became a force to be reckoned with, counterbalancing the influence of the religious right and arguably swinging presidential elections.

And they’re still growing. As recently as 2019, the nones were as numerous as Roman Catholics and evangelicals, the two largest religious groups in America. However, that three-way tie isn’t a tie anymore.

According to a 2024 Pew survey, the nones have moved into the lead:

When Americans are asked to check a box indicating their religious affiliation, 28% now check ‘none.’

A new study from Pew Research finds that the religiously unaffiliated – a group comprised of atheists, agnostic and those who say their religion is “nothing in particular” – is now the largest cohort in the U.S. They’re more prevalent among American adults than Catholics (23%) or evangelical Protestants (24%).“Religious ‘Nones’ are now the largest single group in the U.S.” Jason DeRose, NPR, 24 January 2024.

In the not-too-distant future, if the nones continue this growth, it’s conceivable they could become a majority of Americans—period.

Too good to be true?

Does this sound too good to be true? Then consider the evidence in this post: Which States Are the Least Religious? Which are the Most?, from political scientist Ryan Burge’s site Graphs About Religion.

Based on data from the Cooperative Election Study conducted in 2008 and in 2022, it shows how much American opinions have shifted in just the last fourteen years. Here’s the big picture, which the color coding makes dramatically clear. With the nonreligious population represented in blue, it looks like a tsunami washing across the country:

In 2008, the nones were a minority in every state. Even in the liberal New England states, they were a fraction of the population.

In 2022, the nones have become an outright majority in seven states—Washington, Oregon, Hawaii, Alaska (!), Montana (!), New Hampshire and Maine. Several other states, including California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, are in the high forties. Even in the rural Midwest and the ex-Confederate Deep South, you have to look hard to find a state where the Nones aren’t at least a third of the population.

Some of this may be sampling error, especially in sparsely populated states. Burge notes that those Montana results, for example, are based on just 224 respondents.

Still, the overall trend is dramatic and so sharp as to be undeniable. Their population share has increased everywhere (except, apparently, North Dakota). In some states, like Connecticut, they’ve almost doubled. Georgia and Mississippi are now less religious than Michigan and Colorado were in 2008.

Who’s losing, who’s gaining

Most of this growth has come at the expense of Christians, especially Protestants. And their decline is only getting steeper. As Mark Sumner notes:

The percentage of Americans who call themselves Protestant—including evangelicals—has dropped from 70% in 1953 to 34% in 2022, according to Gallup. That’s a decline of more than 0.5% a year. Since 2016, the rate has averaged 0.67% a year.“Donald Trump is filling the God-shaped hole in Republicans’ lives.” Mark Sumner, Daily Kos, 15 January 2024.

As slow as it can seem on a human scale, on a societal scale, this is a massive and unprecedented shift. The nones have grown in every demographic group that’s been surveyed, both among white people and racial minorities. For example, in a recent Pew survey of Asian American ethnic groups:

Like the U.S. public as a whole, a growing percentage of Asian Americans are not affiliated with any religion, and the share who identify as Christian has declined, according to a new Pew Research Center survey exploring religion among Asian American adults.

…Today, 32% of Asian Americans are religiously unaffiliated, up from 26% in 2012.

Christianity is still the largest faith group among Asian Americans (34%).

But Christianity has also seen the sharpest decline, down 8 percentage points since 2012.

The graying of the church

Of course, there’s no guarantee that the nones will keep growing until we’re a majority in every state. There may be some natural limit that we’ll eventually run into. Or organized religion could go through a spontaneous nationwide revival.

However, there’s another data point that indicates that this cultural shift isn’t going to stop any time soon. Namely, frequent churchgoers are older than the American average. Meanwhile, those younger than the average are even less religious:

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey, 17% of Americans are 65 and older. In FACT’s study, 33% of U.S. congregations are senior citizens.

The other age group where congregations differ dramatically from the U.S. as a whole is 18-34 year olds. Young adults make up 23% of the population but only 14% of churches.“Average U.S. Pastor and Churchgoer Grow Older.” Aaron Earls, Lifeway Research, 1 November 2021.

This means that, as ordinary generational turnover proceeds, we have every reason to expect that religion will keep fading away. The regressive, bigoted and anti-democratic political currents that draw their strength from religion, likewise, will continue to weaken and fragment.

While it won’t solve every problem in the world, it can only be a good thing that religion is losing strength and influence. The toxic manifestations of fundamentalism, which have oppressed humanity and held back progress for so long, are headed for a future of steady decline and eventual disappearance.

Ben Franklin’s noble lie

Here’s the link to this article.

by ADAM LEE DEC 11, 2023

by ADAM LEE DEC 11, 2023

Overview:

In his published works, Benjamin Franklin expressed the misanthropic view that most people can’t behave without religion to keep them in line. What does the evidence say about this noble lie?

Reading Time: 5 MINUTES

When do we need to deceive people for their own good?

Philosophers have debated this question for ages. The optimistic viewpoint holds that there’s never a conflict between truth and goodness. It’s only ignorance that gives rise to evil actions. The smarter and more informed people are, the better they’ll behave.

If this is true, that would be convenient, because it would spare us from having to make unsavory choices. However, some famous historical figures have argued that some truths are too dangerous to spread around. For people’s own good and the good of society, they say, the masses need to be taught falsehoods that keep them in line and make them behave.

The most famous expression of this idea is in Plato’s Republic, where he discusses the noble lie: a mythology taught by elites to make the common people virtuous. What’s shocking is that it was also the view of an American founding father renowned for his wisdom.

“Unchaining the tiger”

Benjamin Franklin wrote a famous letter, responding to an unknown freethinker who sent him a manuscript criticizing religion. We don’t know the identity of Franklin’s correspondent, although some historians argue it was Thomas Paine.

Whoever he was writing to, he expresses a cynical and pessimistic view of human nature:

“I have read your Manuscript with some Attention. By the Arguments it contains against the Doctrine of a particular Providence, tho’ you allow a general Providence, you strike at the Foundation of all Religion: For without the Belief of a Providence that takes Cognizance of, guards and guides and may favour particular Persons, there is no Motive to Worship a Deity, to fear its Displeasure, or to pray for its Protection.

…You yourself may find it easy to live a virtuous Life without the Assistance afforded by Religion; you having a clear Perception of the Advantages of Virtue and the Disadvantages of Vice, and possessing a Strength of Resolution sufficient to enable you to resist common Temptations. But think how great a Proportion of Mankind consists of weak and ignorant Men and Women, and of inexperienc’d and inconsiderate Youth of both Sexes, who have need of the Motives of Religion to restrain them from Vice, to support their Virtue, and retain them in the Practice of it till it becomes habitual… …I would advise you therefore not to attempt unchaining the Tyger… If Men are so wicked as we now see them with Religion what would they be if without it?“

In Poor Richard’s Almanac, Franklin offered a pithier version of the same idea:

“Talking against Religion is unchaining a Tyger; The Beast let loose may worry his Deliverer.”

Notably, this was printed in a book for public consumption. That shows that this wasn’t just his private opinion which he spoke in confidence among friends, but something he was comfortable saying in the open.

The founders’ anti-democratic prejudices

With due respect to Benjamin Franklin, I wonder if he was aware of how misanthropic these words are.

He goes beyond saying that humans are often weak-willed, selfish, or corruptible—something I might be persuaded to agree with. Instead, he compares humanity to a bloodthirsty predator, a dangerous wild animal that’s only kept at bay by a chain. There might be a few wise elites, like Franklin’s correspondent and presumably Franklin himself, who can behave themselves without religious restraints, but most people can’t.

The massive irony of this is that it’s a fundamentally anti-democratic argument. Democracy rests on the basis that the people are the best guardians of their own interests. They can be trusted to decide for themselves. If they’re given the power, they’ll make better choices than distant and uncaring elites.

Franklin’s logic, on the other hand, argues that most people can’t be trusted. It’s too dangerous to let them ask questions, use their own judgment or make up their own minds. Taken to its logical conclusion, this leads straight back to the theory of government that he and America’s other founders rebelled against: that the people should be ruled by aristocrats who know better than the commoners do what’s best for them.

It’s safe to assume that Benjamin Franklin wasn’t the only American founding father who thought this way. When you know that the founders had this deep distrust of the common people, it makes sense that they designed such a creaky, stagnant electoral system, with so many roadblocks against the voters’ will.

By the standards of what existed in the world at the time, the American system was revolutionary. But as the decades pass and our politics become increasingly gridlocked or regressive, it’s showing its age. More truly democratic, more representative systems have proven their worth in creating better results for the people who live under them.

A moral epiphenomenon

There’s an obvious question that, for all Franklin’s wisdom, he never asked: What made him so sure that religion was making people better than they would otherwise have been? How did he know it wasn’t a moral epiphenomenon, sanctifying the beliefs they held already without actually changing their behavior? In fact, how did he know it wasn’t actively making the world worse?

At the time Franklin wrote those words, the United States was overwhelmingly Christian. In fact, most of the colonies had state churches and blasphemy laws which outlawed all dissenting opinions. While there were deists, freethinkers and nonbelievers, most of them kept their opinions quiet or else suffered persecution and punishment.

When it was literally illegal to be an atheist, there was no basis for deciding whether Christianity or atheism was better for instilling morality in the average person. The law was forcing an answer without even permitting the question to be asked.

In fact, in another letter, Franklin contradicted himself by expressing doubt about whether religion was really producing any beneficial effects in the world:

“The Faith you mention has doubtless its use in the World. I do not desire to see it diminished, nor would I endeavour to lessen it in any Man. But I wish it were more productive of good Works, than I have generally seen it: I mean real good Works, Works of Kindness, Charity, Mercy, and Publick Spirit; not Holiday-keeping, Sermon-Reading or Hearing; performing Church Ceremonies, or making long Prayers, filled with Flatteries and Compliments, despis’d even by wise Men, and much less capable of pleasing the Deity. The worship of God is a Duty; the hearing and reading of Sermons may be useful; but, if Men rest in Hearing and Praying, as too many do, it is as if a Tree should Value itself on being water’d and putting forth Leaves, tho’ it never produc’d any Fruit.”

However, in the centuries since then, we’ve obtained enough data to answer this question empirically. Blasphemy laws and other theocratic conceits have been repealed almost everywhere. Especially in the last few decades, religion is in rapid decline.

Has the rise of nonbelief made us worse? Has the country spiraled into chaos without churches holding the whip over us? Have people run wild, killing and pillaging, without the fear of God to keep them in check?

Just the opposite has happened. We’ve become less violent and less warlike. We’ve abolished slavery and other cruel customs. Poverty has declined and literacy has increased. We’ve made great strides toward achieving equal rights under the law for everyone. We’ve become less prejudiced and more tolerant: of immigrants, of all races and cultures, of other religions, of LGBTQ people. The U.S. has become more democratic than it was in the founders’ day, thanks to voting-rights reforms.

To the extent that humanity still believes in cruelty, oppression and prejudice, it’s clearer than ever that religion is to blame for that. Religion sows the seeds of prejudice, inspiring xenophobia and bigotry. It promotes closed-mindedness and hostility to science, to progress, and to new and different ideas. It justifies war and violence in the name of God.

The decline of religion, rather than making us worse, has made us better. We’ve scrapped many of the mystical dogmas that never had any reason behind them. The rules with a genuine connection to human well-being have survived. We’ve also crafted some new ones as social reformers brought to light injustices that had previously been overlooked.

Benjamin Franklin got it wrong. There was never any tiger, no growling, slavering beast ready to pounce on its liberators. Human beings aren’t so vicious as that. It turns out, without that choking chain of religion, we’re more like peaceful lap cats.

A Pop-Quiz for Christians, Number 9

Here’s the link to this article.

By David Madison at 12/08/2023

Tis the season to carefully study the Jesus birth stories

A few years ago I attended the special Christmas show at Radio City Music Hall. It ended with the famous tableau depicting the night Jesus was born: the baby resting on straw in a stable, shepherds and Wise Men adoring the infant, surrounded by farm animals—and a star hovering above the humble shelter. Radio City did it splendidly, of course, but the scene is reenacted at countless churches during the Christmas season. The devout are in awe—well, those who haven’t carefully read the birth stories in Matthew and Luke. This adored tableau is actually a daft attempt to reconcile the two gospel accounts—which cannot, in fact, be done.

If churchgoers actually studied these accounts, they would legitimately ask: How has the church been able to get away with this?

So here are essential questions in this Pop-Quiz:

1. What is the evidence that Jesus was born on December 25?

Read Matthew 1-2 and Luke 1-2: is the evidence there?

2. Where did Mary and Joseph live when they found out she was pregnant?

Matthew and Luke didn’t agree on this.

3. Is it a good idea to add astrology—the ancient superstition of imagining omens in the sky—to Christian theology?

The Wise Men (magi/astrologers) saw the “Jesus star” and set out on a journey to find him. This is mentioned only in Matthew: is there any way at all to make this story credible?

4. What are the problems with that star?

Its behavior changes as the story unfolds.

5. Name two Old Testament verses that Matthew applies to Jesus, but which had nothing whatever to do with Jesus.

Matthew’s use of scripture is eccentric—to put it mildly.

Answers and Comments

Question One: What is the evidence that Jesus was born on December 25?

Events relating to the birth of Jesus are described in only two places in the New Testament: Matthew 1 & 2, and Luke 1 & 2. Mark begins his story with the baptism of Jesus, and John positions Jesus as having been a factor in the creation of the world; he seems not to have cared how Jesus was born as a human. But it was important to Matthew and Luke, yet neither of them bothers to mention the date when Jesus was born. December 25th was chosen later. This article, Why Is Christmas in December? offers details:

“In the 3rd century, the Roman Empire, which at the time had not adopted Christianity, celebrated the rebirth of the Unconquered Sun (Sol Invictus) on December 25th. This holiday not only marked the return of longer days after the winter solstice but also followed the popular Roman festival called the Saturnalia (during which people feasted and exchanged gifts). It was also the birthday of the Indo-European deity Mithra, a god of light and loyalty whose cult was at the time growing popular among Roman soldiers.”

Thus it seems that the Jesus-birthdate is a borrowing, i.e., the church capitalized on the popularity of December 25. But this is a red flag, a warning that there was too much borrowing. It doesn’t take much study of ancient religions to see that virgin birth for gods and heroes was a welcome credential. Matthew and Luke—alone among New Testament authors—attached this credential to Jesus. And while we’re studying ancient religions, we can wonder if December 25 was fiction on a whole different level: was Jesus born at all?

Richard Carrier makes this point:

“Right from the start Jesus simply looks a lot more like a mythical man than a historical one. And were he not the figure of a major world religion—if we were studying the Attis or Zalmoxis or Romulus cult instead—we would have treated Jesus that way from the start, knowing full well we need more than normal evidence to take him back out of the class of mythical persons and back into that of historical ones.” (On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt, p. 602)

Hysteria may be the response of some folks to any suggestion that Jesus was a fictional character. My suggestion: calm down and read Carrier’s book. Find out why, after 600 pages of evidence and reasoning, this is his conclusion. Make the effort to study the gospels carefully, critically: find out why historians don’t trust them to deliver authentic accounts of Jesus. And realize that devout New Testament scholars have been agonizing over this problem for decades.

Question 2: Where did Mary and Joseph live when they found out she was pregnant?

In Matthew’s story, there is no mention whatever of a census that brought Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem. This was simply where they lived, and they fled from there to Egypt—here again, this tall tale is found only in Matthew—to protect Jesus. When they decided to return to their home, it was deemed too dangerous. “And after being warned in a dream, [Joseph] went away to the district of Galilee.There he made his home in a town called Nazareth…” (Matthew 2:22-23) There is not the slightest hint that Mary and Joseph had lived there originally.

Moreover, Luke knew nothing about the escape to Egypt mentioned in Matthew’s account. He offered an extended description of Jesus being taken to the Temple in Jerusalem for circumcision, and the words of adoration spoken about Jesus by two holy people, Simon and Anna. Then it was time to head for home: “When they had finished everything required by the law of the Lord, they returned to Galilee, to their own town of Nazareth.” (Luke 2:39)

It’s puzzling that two gospel authors did not agree on something so basic: where the parents of Jesus lived. And it’s even more puzzling that those who assembled the New Testament would include gospels that didn’t agree. Actually, scholars have been alarmed that the gospel authors fail to agree on so much.

Question Three: Is it a good idea to add astrology—the ancient superstition of imagining omens in the sky—to Christian theology?

The authors of the New Testament had a hard time separating fact from fiction, credible beliefs from superstition. But at least they were inventive. Matthew imagined that astrologers (in the East, presumably Babylon, 900 miles away) figured out that a star represented a new king of the Jews. Why would they care? Why would they embark on a long journey “to pay him homage”? This seems to be a reflection of Matthew’s arrogance that his breakaway Jesus sect was the one true religion. So bring on the “wise men” from other religions!

But astrology was (and remains) an ancient superstition. How does this not drag Christian theology down? Alas, of course, quite a few ancient superstitions in the gospels damage Christianity, e.g., mental illness is caused by demons, people with god-like powers can raise the dead and heal people (Jesus cured a man’s blindness by smearing mud on his eyes), a resurrected human sacrifice guarantees salvation for those who believe. Using astrology to enhance theology is part of a much bigger credibility problem.

Question Four: What are the problems with that star?

Matthew is guilty of a major plot flaw. The astrologers headed to Jerusalem to get information on where to find this new king of the Jews. Their inquiry alarmed King Herod, who made inquiries of the religious experts. They told him that Bethlehem was the place to look, based on a text in Micah 5:2. So the astrologers headed for Bethlehem: “…they set out, and there, ahead of them, went the star that they had seen in the east, until it stopped over the place where the child was.” (Matthew 2:9) Scholar Robert Price has said that the star had suddenly turned into Tinkerbell! Why didn’t it do this earlier, bypassing Jerusalem altogether, thereby keeping King Herod in the dark, and avoiding the Massacre of the Innocents? (Matthew 2:16)

The Tinkerbell Star stopped over the house where Jesus was living—no stable in this story—and Jesus is described as a child or little-boy. When Herod went on his furious rampage later, killing children in the Bethlehem area, the order was to execute those two years old and younger, “according to the time that he had learned from the astrologers.” (Matthew 2:16) After all, 900 miles was a long trek. It is abundantly clear that Matthew depicts an event that did not take place on the night Jesus was born. Placing the Wise Men in Luke’s stable is totally misleading. It makes for good theatre—that’s what appeals to the clergy and Sunday School teachers, I suppose—but it’s not what the Bible says.

Question Five: Name two Old Testament verses that Matthew applied to Jesus, but which had nothing whatever to do with Jesus.

New Testament authors specialized in taking old bits of scripture out of context. They were on the hunt for verses that they could apply to Jesus, no matter the intent of the original authors. Since they were sure that the old documents were filled with secret codes that about their lord, the game was on. Here are two examples:

· In Matthew’s birth story, he quotes Isaiah 7:14 as a prophecy about Jesus. Please read Isaiah 7: how can anything in this text be about a holy hero who would be born centuries later? It is about how Israel’s god will help resolve a crisis at the time.

· As mentioned earlier, it is only Matthew that tells the farfetched story of Mary and Joseph taking Jesus to Egypt to protect him. It would seem this was even too absurd for Luke to believe: he reports that Mary and Joseph—after the circumcision of Jesus—headed back to Nazareth. But Matthew had landed on Hosea 11:1, “When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son.” The reference is clearly to Israel as a people, and moreover, the chapter is a lament that this people had been too ungrateful and rebellious.

Contemporary Bible readers should be able to figure out that Matthew’s use of old texts doesn’t help at all to make the case for Jesus.