Here’s the link to this article. Please take time to read this masterpiece. It’s awe-inspiring, and deeply humbling.

My God, It’s Full of Stars: Henrietta Leavitt, Edwin Hubble, and Our Human Hunger to Know the Universe (Tracy K. Smith Reads Tracy K. Smith)

“…so brutal and alive it seemed to comprehend us back.”

BY MARIA POPOVA

This is the second of nine installments in the animated interlude season of The Universe in Verse in collaboration with On Being, celebrating the wonder of reality through stories of science winged with poetry. See the rest here.

THE ANIMATED UNIVERSE IN VERSE: CHAPTER TWO

In 1908, Henrietta Swan Leavitt — one of the women known as the Harvard Computers, who changed our understanding of the universe long before they could vote — was analyzing photographic plates at the Harvard Observatory, singlehandedly measuring and cataloguing more than 2,000 variable stars — stars that pulsate like lighthouse beacons — when she began noticing a consistent correlation between their brightness and their blinking pattern. That correlation would allow astronomers to measure their distance for the first time, furnishing the yardstick of the cosmos.

Meanwhile, a teenage boy in the Midwest was repressing his childhood love of astronomy and beginning his legal studies to fulfill his dying father’s demand for an ordinary, reputable life. Upon his father’s death, Edwin Hubble would unleash his passion for the stars into formal study and lean on Leavitt’s data to upend millennia of cosmic parochialism, demonstrating two revolutionary facts about the universe: that it is vastly bigger than we thought, and that it is growing bigger by the blink.

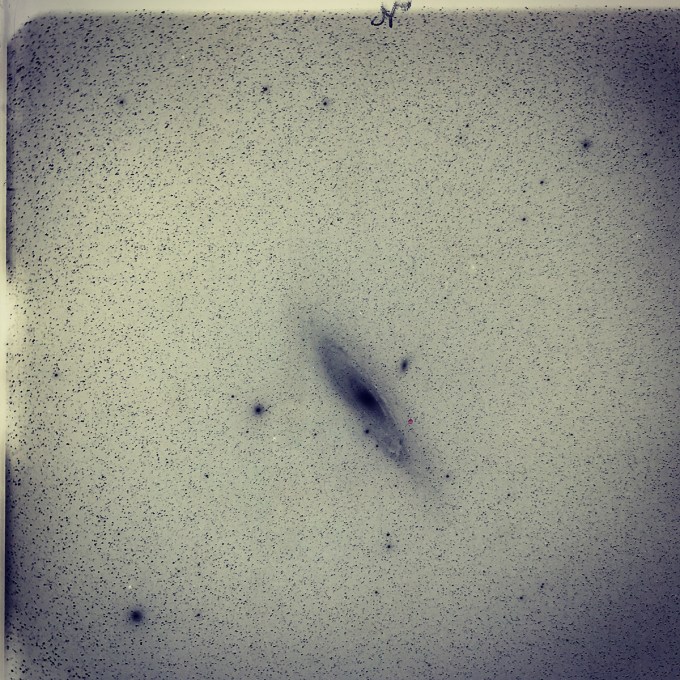

One October evening in 1923, perched at the foot of the world’s most powerful telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory in California, Hubble took a 45-minute exposure of Andromeda, which was then thought to be one of many spiral nebulae in the Milky Way. The notion of a galaxy — a gravitationally bound swirl of stars and interstellar gas, dust and dark matter — did not exist as such. The Milky Way — a name coined by Chaucer — was commonly considered an “island universe” of stars, beyond the edge of which lay cold dark nothingness.

When Hubble looked at the photograph the next morning and compared it to previous ones, he (I like to imagine) furrowed his brow, then with a gasp of revelation he (this we know for a fact) crossed out the marking N on the plate, scribbled the letters V A R beneath it, and could not help adding an exclamation point.

Hubble had realized that a tiny fleck in Andromeda, previously mistaken for a nova, could not possibly be a nova, given its blinking pattern across the different photographs. It was a variable star — which, given Henrietta Leavitt’s discovery, could only be so if the tiny fleck was very far away, farther than the edge of the Milky Way.

Andromeda was not a nebula in our own galaxy but a separate galaxy, out there in the cold dark nothingness.

Suddenly, the universe was a garden blooming with galaxies, with ours but a single bloom.

That same year, in another country suspended between two World Wars, another young scientist named Hermann Oberth was polishing the final physics on a daring idea: to subvert a deadly military technology with roots in medieval China and rocket-launch an enormous telescope into Earth orbit — closer to the stars, bypassing the atmosphere that occludes our terrestrial instruments.

It would take two generations of scientists to make that telescope a reality — a shimmering poem of metal, physics, and perseverance, bearing Hubble’s name.

But when the Hubble Space Telescope finally launched 1990, hungry to capture the most intimate images of the cosmos humanity had yet seen, humanity had crept into the instrument’s exquisite precision — its main mirror had been ground into the wrong spherical shape, warping its colossal eye.

Up the coast from Mount Wilson Observatory, a teenage girl watched her father — who had worked on the Hubble as one of NASA’s first black engineers — come home brokenhearted. He didn’t know that his observant daughter would become Poet Laureate of his country and would come to commemorate him in the tenderest tribute an artist-daughter has ever made for a scientist-father. That tribute — the splendid poetry collection Life on Mars (public library) — earned Tracy K. Smith the Pulitzer Prize the year the Hubble’s corrected optics captured the revolutionary Ultra Deep Field image of the observable universe, revealing what neither Henrietta Leavitt nor Edwin Hubble could have imagined — that there isn’t just one other galaxy besides our own, or just a handful more, but at least 100 billion, each containing at least 100 billion stars.

MY GOD, IT’S FULL OF STARS (PART 5)

by Tracy K. SmithWhen my father worked on the Hubble Telescope, he said

They operated like surgeons: scrubbed and sheathed

In papery green, the room a clean cold, a bright white.He’d read Larry Niven at home, and drink scotch on the rocks,

His eyes exhausted and pink. These were the Reagan years,

When we lived with our finger on The Button and struggledTo view our enemies as children. My father spent whole seasons

Bowing before the oracle-eye, hungry for what it would find.

His face lit up whenever anyone asked, and his arms would riseAs if he were weightless, perfectly at ease in the never-ending

Night of space. On the ground, we tied postcards to balloons

For peace. Prince Charles married Lady Di. Rock Hudson died.We learned new words for things. The decade changed.

The first few pictures came back blurred, and I felt ashamed

For all the cheerful engineers, my father and his tribe. The second time,

The optics jibed. We saw to the edge of all there is —So brutal and alive it seemed to comprehend us back.

THE MAKING

Every poet is a miniaturist of meaning, building cathedrals of beauty and truth with the smallest particles of language. It is with a poet’s mindset that Brazilian graphic artist and animation director Daniel Bruson approached his contribution to The Universe in Verse. (Special thanks to On Being creative director Erin Colasacco for bringing Daniel into the project and for working with him and with composer Gautam Srikishan on making this symphonic cinepoem come alive.)

After I relayed to Daniel why I had chosen this particular poem (which Tracy read at the inaugural Universe in Verse in 2017) to illustrate the larger story of our search for cosmic truth — a search both made possible and made imperfect by our humanity — he grasped the nested layers of meaning with uncommon sensitivity, mirroring back his interpretation:

The Hubble tries to see or make sense of the Universe, the father tries to understand the Hubble, the daughter tries to make sense of the father, the decade, the world, and the poet tries to put this whole into perspective. All these efforts have to face problems of scale or distortion: something too big or small, too close or too distant, too dark or too familiar. Not to mention the original problem with the Hubble mirror.

This cascade of distortion sparked the idea “to use optics as a metaphor, to seek for these imperfect, unresolved and elusive, but also suggestive and alive images.”

Daniel set about creating his deliberately blurry cosmic animations frame by frame, painting each tiny detail onto a glass plate with nail polish, oil paint, glitter, acrylic, and other materials he mixed, scrubbed, smudged, and swirled with brushes and cotton swabs beneath the lens of a camera capturing the process of creation and destruction.

He magnified the optical enchantment by filming the vignettes through upside-down drinking glasses of various shapes and thicknesses.

In a crowning feat of ingenuity — itself a miniature masterpiece of engineering and composition — he built a tiny model of the Hubble out of cardboard, paper, and aluminum foil, dismantled it frame by frame, filmed the destruction, then reversed the footage to create the building effect. (I am reminded here of Bertrand Russell’s astute observation, made shortly after Edwin Hubble took his historic glass plate of Andromeda, that “construction and destruction alike satisfy the will to power, but construction is more difficult as a rule, and therefore gives more satisfaction to the person who can achieve it” — a truth as true of the universe itself, with its elemental triumph of something over nothing, as it is of the human endeavor to know it by building optical prosthesis of our curiosity.)

Something about Daniel’s process — the exquisite craftsmanship, the passionate patience, the tiny scale on which he made such beauty and grandeur of feeling — calls to mind Emily Dickinson and her miniature cherrywood writing desk, on the seventeen square inches of which she conjured up such cosmoses of truth, among them the poem illustrating Chapter One of this series.