Here’s the link to this article.

Most delegates still oppose women pastors, IVF is evil, and abuse reform can wait. But at least the new president doesn’t wear jeans in the pulpit.

JUN 13, 2024

The Southern Baptist Convention, which has been dealing with a massive sexual abuse crisis for years now, finally got its priorities in order this week at its annual meeting… by threatening churches that believe women can serve as pastors and agreeing that in vitro fertilization is “dehumanizing” and must be opposed at all costs.

Let’s start with the sexism.

On Tuesday, delegates (“Messengers“) at the convention voted overwhelmingly (6,759-563) to expel Virginia’s First Baptist Church of Alexandria, a church that currently has a woman serving as “Pastor for Children and Women” and openly declares on its website that the Bible “not only permits women to serve in the offices of pastor and deacon but confirms this with examples by name.”

The church saw the writing on the wall two years ago when they were first ratted out for their disobedience. It didn’t matter that the church, which has existed for well over a century, donated millions of dollars to the SBC for missionary work. The Associated Press said that “the pastor of a neighboring church reported” them to the SBC after discovering they employed two women as pastors. (A man was still the “senior pastor,” but that was irrelevant.)

Their open belief that there’s nothing wrong with having women on staff as pastors is what pushed the SBC over the edge.

The vote came after the denomination’s credentials committee recommended earlier Tuesday that the denomination deem the church to be not in “friendly cooperation,” the formulation for expulsion, on the grounds that it conflicts with the Baptist Faith and Message. That statement of Southern Baptist doctrine declares only men are qualified for the role of pastor. Some interpret that only to apply to associate pastors as long as the senior pastor is male.

It would be unfair to call this church progressive given that it opposes same-sex marriage and denies the existence of transgender people, but even symbolic gender equality was a bridge too far for most Southern Baptists who voted.

The expulsion came a year after the SBC kicked out Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church for ordaining three female pastors.

But all of that was merely a prelude to what happened Wednesday when the SBC voted on a formal policy (called the “Law Amendment,” after the name of the person who proposed it) to banish any SBC church that placed women on the leadership hierarchy or openly supported that idea.

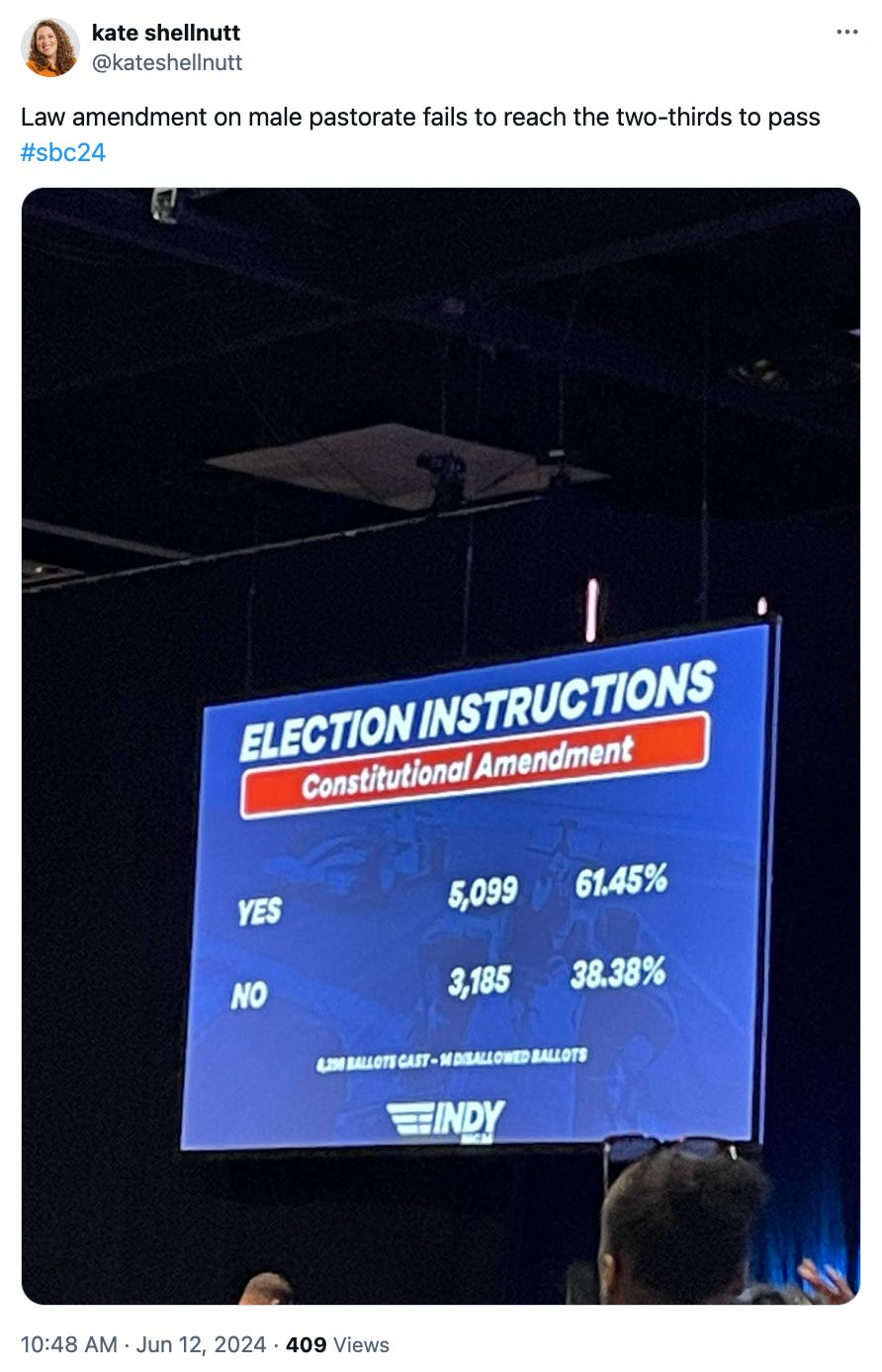

The policy, which needed two-thirds of the vote, two years in a tow, ultimately failed. They couldn’t get over the 67% threshold this time around.

Still, it’s hardly a victory when over 60% of SBC delegates support the Only-Men-In-Power doctrine. (Had this Amendment passed, the First Baptist Church of Alexandria would have been expelled from the SBC for having a female pastor and believing women can be co-equal leaders. As it stands, they were only kicked out for the latter offense.)

As reporter Kate Shellnutt of Christianity Today explained, the SBC will still be able to punish churches with “female lead pastors,” like they did with Saddleback, but they won’t have a zero tolerance policy for churches that place women in other leadership positions.

Had the Law Amendment passed, it could have led many churches to step out from under the SBC umbrella, as Bob Smietana noted at Religion News Service:

Southern Baptist churches have long relied on women to teach Sunday School, lead outreach ministries and do all the behind-the-scenes work to keep their congregations running smoothly. Southern Baptists also raise hundreds of millions of dollars every year in the names of legendary missionaries Lottie Moon and Annie Armstrong. But they have also banned women from the pastorate — especially serving as senior pastor of a church.

… Passing this new rule, known as the “Law Amendment,” could lead to hundreds or thousands of churches leaving the SBC.

Just because the vote failed, however, doesn’t mean those churches will stay put.

The fact that this rule—no women in church leadership!—was even an issue tells you a lot about where the SBC is at. They’re literally arguing about a mild version of gender equality while the rest of their house remains on fire. Sexual abuse runs rampant within the SBC but a large part of the focus this year was on whether a woman serving as associate pastor was substantially different from a woman serving as senior pastor. For the majority of delegates, it’s better to have women labeled as servants and let them keep doing the same work, I guess.

Had they chosen to expel churches that employ women as pastors, the expectation was that a lot of churches would quit before they could be fired. Some still may.

Some churches made the decision to leave before they might be asked.

…

The Rev. Christy McMillin-Goodwin, pastor of First Baptist Church in Front Royal, Virginia, said she was surprised to discover that another Virginia clergyperson had listed her church as an example of one whose clerical leader was “sinning against God.”

“Our church decided to take a vote last May (2023) and the decision was unanimous,” she said of the church that had long stopped sending donations to the SBC and is affiliated with the more moderate Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. “People actually yelled ‘Yes.’ It was very impassioned that we don’t want to be a part of an organization that does not fully support women in leadership in the church.”

They were proud to be part of a historically racist and currently anti-LGBTQ organization, but punishing churches that have women in leadership was a dealbreaker? Got it. (Someone make that make sense.)

It’s not just slightly progressive churches that need to decide their membership status. A lot of Black churches are making similar decisions, turning an organization that’s already known for its support of white Christian Nationalism into one that more closely looks the part.

When that happens, it will be a completely self-inflicted wound.

Telling women they’re equally capable of spreading the Gospel seems to be the sort of thing that would draw in more Christians than it alienates. But dogma, for many of these Southern Baptists, overrides common sense. The majority of Southern Baptists want to force underage girls to bear their rapists’ babies but they can’t handle a grown woman in the pulpit.

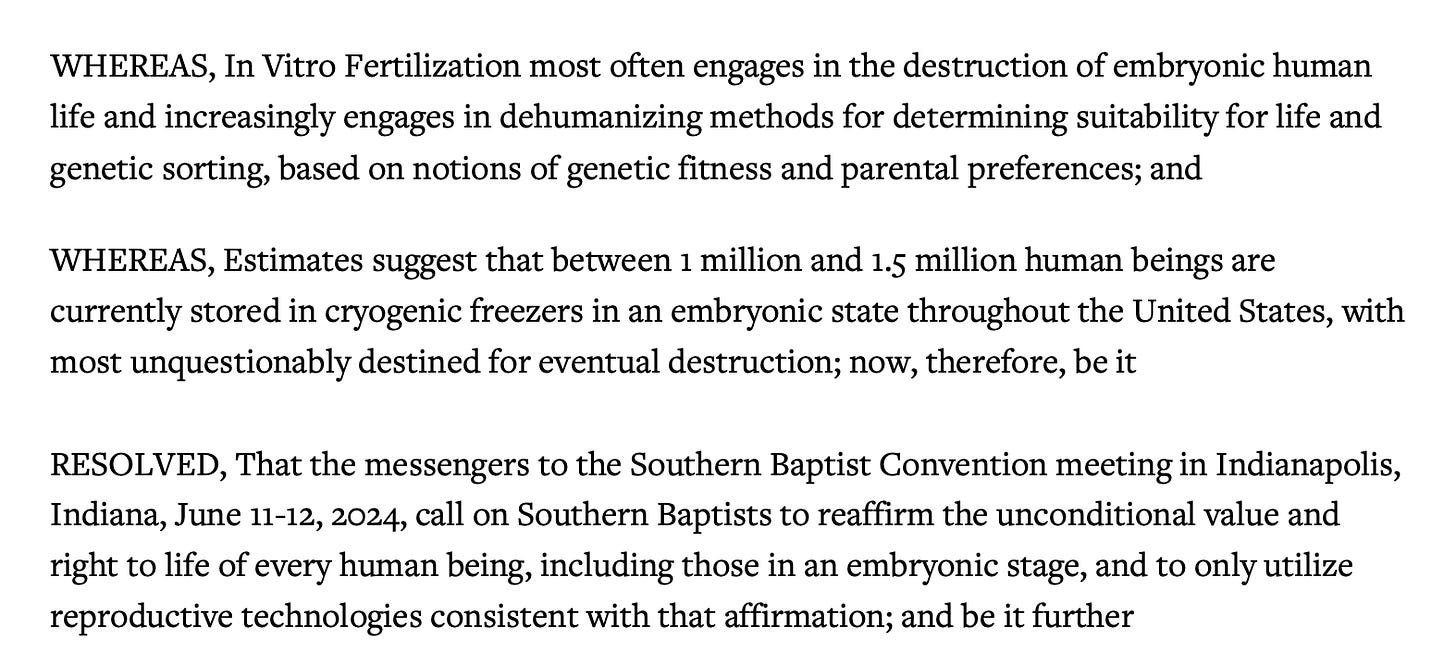

On top of that, the SBC also voted to oppose IVF treatments, even though plenty of white evangelicals have used the technology to have babies. While the vote wasn’t a surprise, it’s an extreme approach that may signal the next phase in the Christian Nationalist attack on reproductive rights.

IVF, of course, is a procedure in which a sperm and ova are joined outside the body, in a laboratory dish. It’s meant to help couples struggling with infertility or other health problems. The concern for anti-abortion extremists is that, in IVF, the embryos that aren’t implanted inside a uterus may be discarded or placed in a freezer. They believe that’s tantamount to murder. (Oklahoma State Senator Dusty Deevers has said parents who use IVF are “waging an assault against God.”)

If you cut through the fluff in the actual SBC amendment, these paragraphs are what it boils down to:

IVF destroys human life. IVF promotes eugenics. IVF will lead to the murder of millions of teeny tiny “human beings.” Therefore we must oppose IVF no matter what.

It’s a thoughtless statement from a heartless organization.

It’s also a slap in the face to all the Christian women who have used IVF to have babies because, without it, they were unable to have children.

While the resolution has no teeth, and people who use IVF will still be allowed to stay in their churches, it’s a signal that conservative Christians are not satisfied with the Supreme Court banning abortion rights and that they fully intend to support politicians who want to ban IVF, too. They will also use this vote to put more pressure on Republicans who support IVF because it’s overwhelmingly popular.

POLITICO puts it bluntly:

Though the resolution is nonbinding, nearly 13 million Southern Baptists across 45,000 churches may now face pressure from the pulpit or in individual conversations with pastors to eschew IVF.

…

The Southern Baptists’ Wednesday vote could encourage other evangelical denominations and churches to follow suit in declaring — or at least teaching about — their ethical concerns with IVF.

All of this is happening while membership in the SBC is at a 47-year low.

In 2003, the SBC had a record high 16.3 million members. In 2023, the number dropped to 12.99 million, continuing 17 straight years of declining membership.

Meanwhile, the sexual abuse crisis remains a massive problem for the SBC.

It all stems back to revelations from 2022 about the SBC, in which we learned that, over the previous decade, more than 250 SBC staffers or volunteers had been “charged with sex crimes” against more than 700 victims. We also learned in the SBC’s own investigation that a private list of alleged predators (that wasn’t shared with member churches) included “703 abusers, with 409 believed to be SBC-affiliated.” The situation was so bad that the Department of Justice announced it was investigating “multiple SBC entities,” though not specific individuals, about their mishandling of sexual abuse cases. Last month, a former seminary professor became the first person indicted in the investigation. (He has pleaded not guilty.)

This month, we got an update from the SBC as to how its internal investigations are going… and it was predictably disappointing. A volunteer task force that was supposed to implement reforms announced that it would close up shop. While they created some resources to help churches deal with the problem, the biggest reform they could have made was creating a database of abusers so that criminals and known problematic people couldn’t church-hop after getting kicked out of one place… but that “Ministry Check” never happened because of a lack of funding and fears over getting sued.

To date, no names appear on the “Ministry Check” website designed to track abusive pastors, despite a mandate from Southern Baptists to create the database. The committee has also found no permanent home or funding for abuse reforms, meaning that two of the task force’s chief tasks remain unfinished.

Because of liability concerns about the database, the task force set up a separate nonprofit to oversee the Ministry Check website. That new nonprofit, known as the Abuse Response Committee, has been unable to publish any names because of objections raised by SBC leaders.

The SBC raked in over $10 billion in 2023. They could fund abuse reforms if they really wanted to without even noticing a change in their bank account. They just don’t want to. They would rather form a task force with no teeth than risk the world finding out just how many of their leaders are alleged (or charged) abusers.

When Lifeway Christian Resources (an arm of the SBC) released the results of a survey of congregation leaders last month, they found that only 58% of them required background checks for staffers who work with kids. With the number that low, the abuse is bound to continue.

Lost in the shuffle of all these votes was the election of the SBC’s new president, Clint Pressley, a megachurch pastor from North Carolina who represents the more conservative wing of the already conservative denomination. (The Religion News Service article about his election says, in the first paragraph, that Pressley “does not wear jeans in the pulpit.” Because that would be heretical.)

Pressley supported the anti-women Law Amendment and had “questions” about the proposed database of abusers, in case you had any questions about where he stands. Oh. And a volunteer at his megachurch was arrested in May after being accused of sexually abusing his own daughter. (The church thankfully reported the man to secular authorities leading to his eventual arrest.)

Keep in mind that the second largest Protestant denomination recently voted to get rid of its anti-LGBTQ policies and allow gay clergy members.

The SBC, on the other hand, is still debating which way to rearrange deck chairs on the Titanic.

(Portions of this article were published earlier)

Please share this post on Reddit, Facebook, or the godawful X/Bird app.

Subscribe to Friendly Atheist

By Hemant Mehta · Hundreds of paid subscribers

Commentary about religion and politics, centered around atheism.