The following excerpts are taken from Chapter 1 of Adam Grant’s book, Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know. The title of this chapter is “A Preacher, a Prosecutor, a Politician, and a Scientist Walk into Your Mind.” Since these are all Adam’s words, I’ve omitted quotation marks. However, emphasis is my own.

Of course, I recommend you purchase and read Adam’s book. Here’s the link.

Adam’s thoughts

We need to spend as much time rethinking as we do thinking.

SECOND THOUGHTS

With advances in access to information and technology, knowledge isn’t just increasing. It’s increasing at an increasing rate. In 2011, you consumed about five times as much information per day as you would have just a quarter century earlier. As of 1950, it took about fifty years for knowledge in medicine to double. By 1980, medical knowledge was doubling every seven years, and by 2010, it was doubling in half that time.

The accelerating pace of change means that we need to question our beliefs more readily than ever before. This is not an easy task. As we sit with our beliefs, they tend to become more extreme and more entrenched. I’m still struggling to accept that Pluto may not be a planet. In education, after revelations in history and revolutions in science, it often takes years for a curriculum to be updated and textbooks to be revised. Researchers have recently discovered that we need to rethink widely accepted assumptions about such subjects as Cleopatra’s roots (her father was Greek, not Egyptian, and her mother’s identity is unknown); the appearance of dinosaurs (paleontologists now think some tyrannosaurs had colorful feathers on their backs); and what’s required for sight (blind people have actually trained themselves to “see”—sound waves can activate the visual cortex and create representations in the mind’s eye, much like how echolocation helps bats navigate in the dark).* Vintage records, classic cars, and antique clocks might be valuable collectibles, but outdated facts are mental fossils that are best abandoned.

We’re swift to recognize when other people need to think again. We question the judgment of experts whenever we seek out a second opinion on a medical diagnosis. Unfortunately, when it comes to our own knowledge and opinions, we often favor feeling right over being right. In everyday life, we make many diagnoses of our own, ranging from whom we hire to whom we marry. We need to develop the habit of forming our own second opinions.

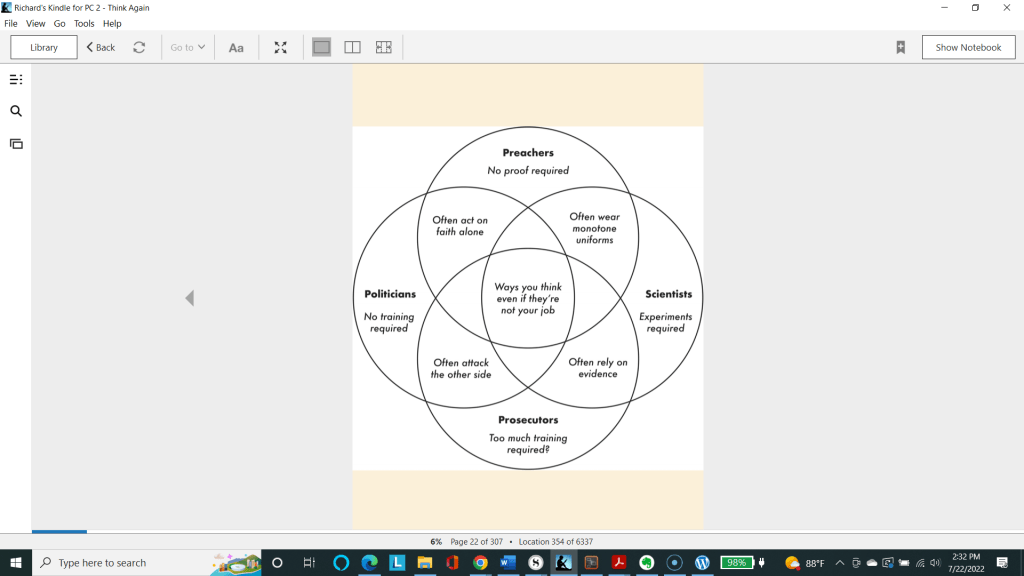

As we think and talk, we often slip into the mindsets of three different professions: preachers, prosecutors, and politicians. In each of these modes, we take on a particular identity and use a distinct set of tools. We go into preacher mode when our sacred beliefs are in jeopardy: we deliver sermons to protect and promote our ideals. We enter prosecutor mode when we recognize flaws in other people’s reasoning: we marshal arguments to prove them wrong and win our case. We shift into politician mode when we’re seeking to win over an audience: we campaign and lobby for the approval of our constituents. The risk is that we become so wrapped up in preaching that we’re right, prosecuting others who are wrong, and politicking for support that we don’t bother to rethink our own views.

A DIFFERENT PAIR OF GOGGLES

If you’re a scientist by trade, rethinking is fundamental to your profession. You’re paid to be constantly aware of the limits of your understanding. You’re expected to doubt what you know, be curious about what you don’t know, and update your views based on new data. In the past century alone, the application of scientific principles has led to dramatic progress. Biological scientists discovered penicillin. Rocket scientists sent us to the moon. Computer scientists built the internet. But being a scientist is not just a profession. It’s a frame of mind—a mode of thinking that differs from preaching, prosecuting, and politicking.

We move into scientist mode when we’re searching for the truth: we run experiments to test hypotheses and discover knowledge. Scientific tools aren’t reserved for people with white coats and beakers, and using them doesn’t require toiling away for years with a microscope and a petri dish. Hypotheses have as much of a place in our lives as they do in the lab. Experiments can inform our daily decisions. That makes me wonder: is it possible to train people in other fields to think more like scientists, and if so, do they end up making smarter choices?

Just as you don’t have to be a professional scientist to reason like one, being a professional scientist doesn’t guarantee that someone will use the tools of their training. Scientists morph into preachers when they present their pet theories as gospel and treat thoughtful critiques as sacrilege. They veer into politician terrain when they allow their views to be swayed by popularity rather than accuracy. They enter prosecutor mode when they’re hell-bent on debunking and discrediting rather than discovering. After upending physics with his theories of relativity, Einstein opposed the quantum revolution: “To punish me for my contempt of authority, Fate has made me an authority myself.” Sometimes even great scientists need to think more like scientists.

THE SMARTER THEY ARE, THE HARDER THEY FAIL

Mental horsepower doesn’t guarantee mental dexterity. No matter how much brainpower you have, if you lack the motivation to change your mind, you’ll miss many occasions to think again. Research reveals that the higher you score on an IQ test, the more likely you are to fall for stereotypes, because you’re faster at recognizing patterns. And recent experiments suggest that the smarter you are, the more you might struggle to update your beliefs.

One study investigated whether being a math whiz makes you better at analyzing data. The answer is yes—if you’re told the data are about something bland, like a treatment for skin rashes. But what if the exact same data are labeled as focusing on an ideological issue that activates strong emotions—like gun laws in the United States? Being a quant jock makes you more accurate in interpreting the results—as long as they support your beliefs. Yet if the empirical pattern clashes with your ideology, math prowess is no longer an asset; it actually becomes a liability. The better you are at crunching numbers, the more spectacularly you fail at analyzing patterns that contradict your views. If they were liberals, math geniuses did worse than their peers at evaluating evidence that gun bans failed. If they were conservatives, they did worse at assessing evidence that gun bans worked.

In psychology there are at least two biases that drive this pattern. One is confirmation bias: seeing what we expect to see. The other is desirability bias: seeing what we want to see. These biases don’t just prevent us from applying our intelligence. They can actually contort our intelligence into a weapon against the truth. We find reasons to preach our faith more deeply, prosecute our case more passionately, and ride the tidal wave of our political party. The tragedy is that we’re usually unaware of the resulting flaws in our thinking. My favorite bias is the “I’m not biased” bias, in which people believe they’re more objective than others. It turns out that smart people are more likely to fall into this trap. The brighter you are, the harder it can be to see your own limitations. Being good at thinking can make you worse at rethinking.

When we’re in scientist mode, we refuse to let our ideas become ideologies. We don’t start with answers or solutions; we lead with questions and puzzles. We don’t preach from intuition; we teach from evidence. We don’t just have healthy skepticism about other people’s arguments; we dare to disagree with our own arguments. Thinking like a scientist involves more than just reacting with an open mind. It means being actively open-minded. It requires searching for reasons why we might be wrong—not for reasons why we must be right—and revising our views based on what we learn.

That rarely happens in the other mental modes. In preacher mode, changing our minds is a mark of moral weakness; in scientist mode, it’s a sign of intellectual integrity. In prosecutor mode, allowing ourselves to be persuaded is admitting defeat; in scientist mode, it’s a step toward the truth. In politician mode, we flip-flop in response to carrots and sticks; in scientist mode, we shift in the face of sharper logic and stronger data.

DON’T STOP UNBELIEVING

As I’ve studied the process of rethinking, I’ve found that it often unfolds in a cycle. It starts with intellectual humility—knowing what we don’t know. We should all be able to make a long list of areas where we’re ignorant. Mine include art, financial markets, fashion, chemistry, food, why British accents turn American in songs, and why it’s impossible to tickle yourself. Recognizing our shortcomings opens the door to doubt. As we question our current understanding, we become curious about what information we’re missing. That search leads us to new discoveries, which in turn maintain our humility by reinforcing how much we still have to learn. If knowledge is power, knowing what we don’t know is wisdom.

Scientific thinking favors humility over pride, doubt over certainty, curiosity over closure. When we shift out of scientist mode, the rethinking cycle breaks down, giving way to an overconfidence cycle. If we’re preaching, we can’t see gaps in our knowledge: we believe we’ve already found the truth. Pride breeds conviction rather than doubt, which makes us prosecutors: we might be laser-focused on changing other people’s minds, but ours is set in stone. That launches us into confirmation bias and desirability bias. We become politicians, ignoring or dismissing whatever doesn’t win the favor of our constituents—our parents, our bosses, or the high school classmates we’re still trying to impress. We become so busy putting on a show that the truth gets relegated to a backstage seat, and the resulting validation can make us arrogant. We fall victim to the fat-cat syndrome, resting on our laurels instead of pressure-testing our beliefs.

Our convictions can lock us in prisons of our own making. The solution is not to decelerate our thinking—it’s to accelerate our rethinking.

The curse of knowledge is that it closes our minds to what we don’t know. Good judgment depends on having the skill—and the will—to open our minds. I’m pretty confident that in life, rethinking is an increasingly important habit. Of course, I might be wrong. If I am, I’ll be quick to think again.