I’m currently taking a writing and blogging sabbatical due to family health issues. For now, I’ll repost selected articles from my Fiction Writing School.

Here is the link to this article.

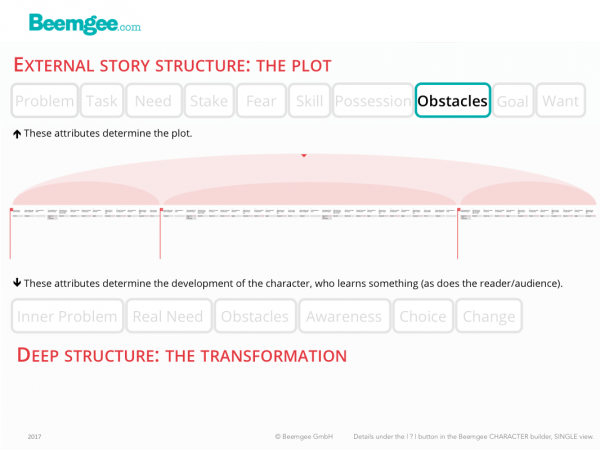

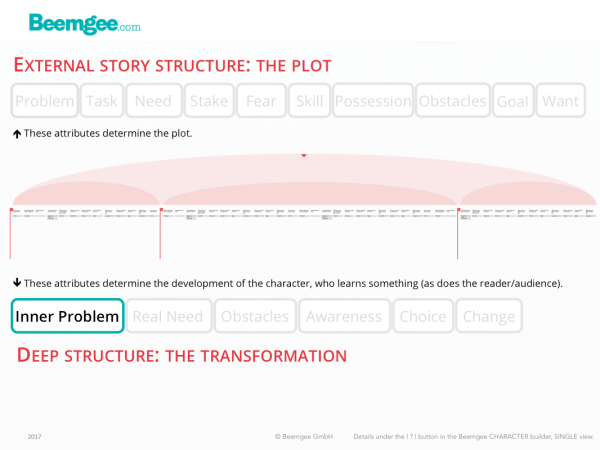

The internal problem is a character’s psychological or emotional flaw, weakness or shortcoming – and is often what makes the character interesting. So the internal problem is usually a negative and harmful character trait, possibly one that led to terrible mistake the character has made in the past. Watching the character resolve this inner issue by causing a change is what the story is really about, on a deeper level than the surface structure of the plot. So the author and the readers/audience need to know what the internal problem is – although the character may not. At least not until the middle or near the end of the narrative, when the realisation of this internal problem (gaining awareness) marks the beginning of its being (re)solved. What is this character’s issue?

An inner or internal problem is the chance for change.

While the external problem shows the audience the character’s motivation to act (he or she wants to solve the problem), it is the internal problem that gives the character depth.

In storytelling, the internal problem is a character’s weakness, flaw, lack, shortcoming, failure, dysfunction, error, miscalculation, or mistake. It is often manifested to the audience through a negative character trait. Classically, this flaw may be one of excess, such as too much pride. Almost always, the internal problem involves egoism. By overcoming it, the character will be wiser at the end of the story than at the beginning. Thus the character must learn cooperative behaviour in order to be a mature, socially functioning person.

The inner problem is the pre-condition for the character’s transformation. It is the flaw, weakness, mistake, error, or deficit that needs to be fixed. In other words, it shows what the character needs to learn.

Internal problems may be character traits that cause harm or hurt to others. They cause anti-social behaviour. And internal problems can also harm the character. They can be detrimental to his or her solving the external problem.

From Lack of Awareness to Revelation

While the external problem provides a character’s want, i.e. motivation, the internal problem provides the need.

The audience sees the flaw before the character does. The character is blinkered, has a blind spot. She first has to learn to see what the audience already knows. At the beginning of the story the internal problem is a hindrance to the character’s emotional growth and even causes the character to hurt others. But eventually it may give rise to awareness or self-revelation. The character will recognise the internal problem and understand that it is harmful to him or herself or to others, and really needs to be solved.

The Internal Problem of a character is revealed to the audience in scenes that show the symptoms of the flaw for the character and her environment. It results in internal obstacles, specific instances of the character’s flaw which prevent her from progressing directly towards her goal. Furthermore, the antagonism in the story may well be a sort of symbolic manifestation of the protagonist’s internal problem.

So a character may initially not be aware of his or her internal problem. A character trait, after all, is something that has been in a character for a long time – since before the beginning of the story. In real life, the origin of behaviour patterns is seldom so singular and specific, but for authors of stories it helps to have scenes in mind for:

- a scene early in the narrative that shows the audience the character’s flaw,

- a “confirmation bias” moment, the outcome of which is that the character’s flawed belief or worldview is reinforced,

- another incident that “touches the nerve” of our flawed character in such a way as to lead them to arduously defend themselves and their flaw, revealing the extent of their internal problem to the audience,

- a scene which shows the character recognising the first cracks in the flawed world view, an initial revelation – often in the middle of the narrative,

- a particular instance that is the origin or root cause of the character flaw,

- the scene which demonstrates whether the character has fully recognised the problem and has learnt to act in such a way that the audience may now consider it solved.

The scenes don’t necessarily appear to the audience in that order. Since the inner problem was caused long before the story starts, all this seems to invite backstory scenes to explain its origin. But beware, there is a subtle writer trap here. More about that below.

The Problem Gives Rise to A Need

So: A character wants a certain state of being, a particular situation such as wealth, power, happiness, being in a relationship, owning a desired object. The character may believe this will be attained upon achieving a particular goal, the apparent manifestation of the solution to the external problem. However, once the character has reached the goal, it may transpire that the goal is not at all what the character needs in order to achieve the want. The full extent of the real need was perhaps suppressed by the character up to now, because it requires a change in character, which is to say a change of the negative character trait to a positive one.

In other words, growth. The character will grow by solving the internal problem. The internal problem is an emotional immaturity in the character. The real need the internal problem spawns is for emotional growth. This growth will turn the character into a person whose actions are no longer detrimental to the self, and who acts well towards others, i.e. with social responsibility.

That all sounds moralistic, which is a writer trap.

Writer Traps

We all know stories in which characters learn something and become better people by overcoming negative character traits. Very direct examples are the ones where a young protagonist helps a grumpy old person to redeem him or herself, such as True Grit or Scent Of A Woman. The idea of a main character having to learn something is so fundamental that its effects are visible in virtually all stories, especially – but not only – in ones from Hollywood.

Yes, the audience or reader should become aware of the internal problem of the character. And here’s how to avoid the morality trap: The internal problem should not be presented as something unforgivably reprehensible, but as a trait which the audience or reader recognises in themselves – to an extent at least. The more obviously anti-social the effects of the internal problem, the more the story turns into a morality piece. Generally speaking, the audience is more likely to have an emotional response to the story when the story does not transport a moral or the author’s intended meaning too explicitly. The audience is happier feeling it for themselves rather than having it spelled out to them.

And as for the backstory trap, this one is a doozy.

These days, for the last hundred years or so, we have a tendency to look for the origin of negative character traits in our own histories, often in the form of more or less powerful traumas suffered in our childhoods. Sigmund Freud has influenced storytelling here. Many modern stories provide explanations of the internal problem of a character by presenting a traumatic event which occurred in that character’s past. The film director Sidney Lumet mocks the “rubber-ducky” explanation scene: “Someone once took his rubber ducky away from him, and that’s why he’s a deranged killer.” A topos that has become a particular cliché in modern storytelling is child abuse. The protagonist was molested as a child; that explains the anti-social behaviour; confronting the trauma leads to its healing. Such simplistic explanations are writer traps.

It is quite possible to use a specific event in a character’s past as the cause of the internal problem without it turning into cliché. Speaking from a purely dramaturgical perspective, in terms of story structure there are alternatives to trauma. The ancient classics did not use traumatic events to provide an internal problem for a character to solve. Most older stories don’t try to find such psychological explanations – they are often less about trauma and more about errors of judgment. About mistakes.

Everyone makes mistakes. Everyone makes bad decisions sometimes. A bad call does not mean there needs to be a trauma. A bad call is usually simply the result of emotional immaturity.

So, the event that led to the internal problem does not have to bear Freud’s influence. The event could be a simple mistake a character made once upon a time, which comes back much, much later to haunt that character. An example from the ancient classics would be Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex.

Classically then, the internal problem is the cause of the external problem. Even stories that don’t manage to achieve this level of neatness will try to establish some connection between the external and the internal problems. In stories where the protagonist is her or his own worst enemy, such as Leaving Las Vegas, the internal problem becomes the antagonistic force.

To read more of Beemgee’s writing craft articles click here